The American Revolution: Going Dutch, French and Spanish

Contextual Essay

The American Revolution was a war of political and economic concern to more than the American colonies and Great Britain. Each country needed to secure military supplies, protect consumer trade and ensure the cooperation of foreign powers. France, Spain, Holland, Portugal and Caribbean territories engaged in activities which directly affected events of the war. By broadening the scope of the war, students should develop a broader perspective of the diplomacy and business of war.

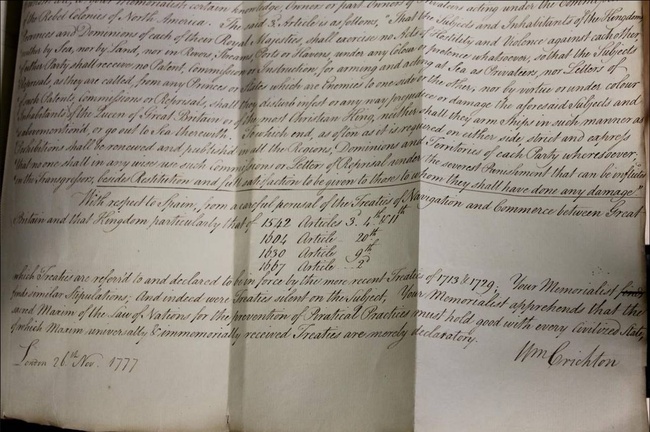

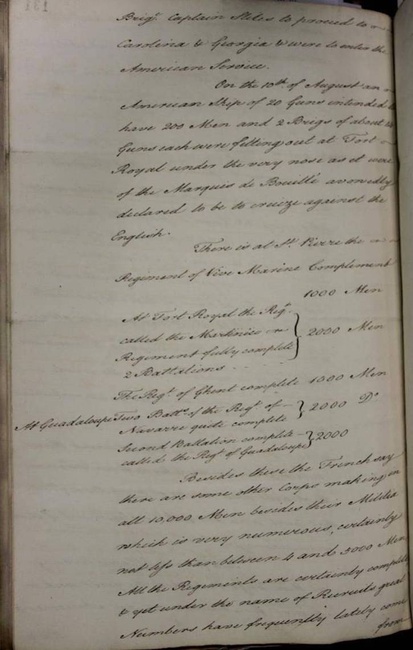

The American colonies were at a significant disadvantage when fighting a war with Great Britain. Great Britain had large, experienced navy and far-reaching trade networks. The American colonies lacked a fleet of ships equipped to fight battles or to facilitate trade. To compensate for this shortcoming, foreign allies were sought and privateers were authorized (Stock). The purpose of the foreign allies was to negotiate support. Diplomats sought funding with the promise repayment (Considering) and the potential profit of becoming a trade partner. The privateers were intended to secure needed supplies, disrupt British trade and discourage British popular support.

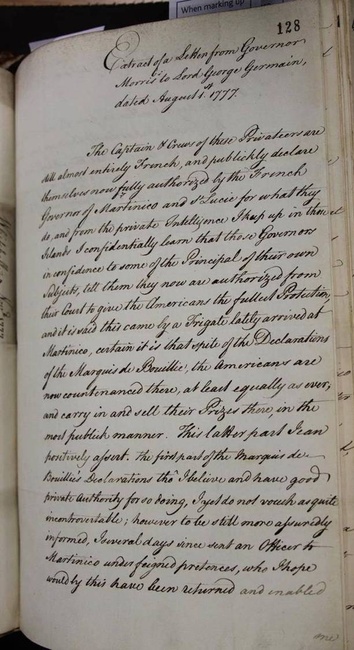

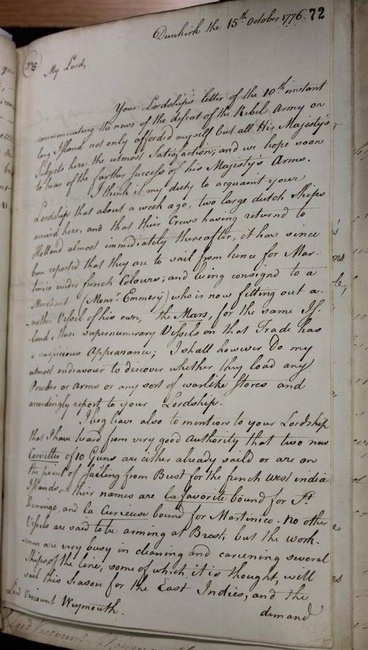

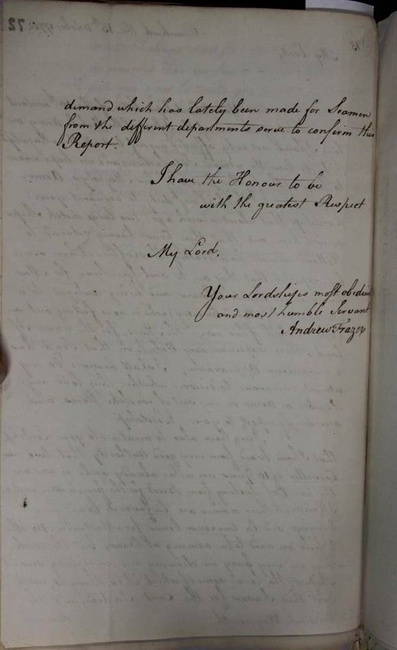

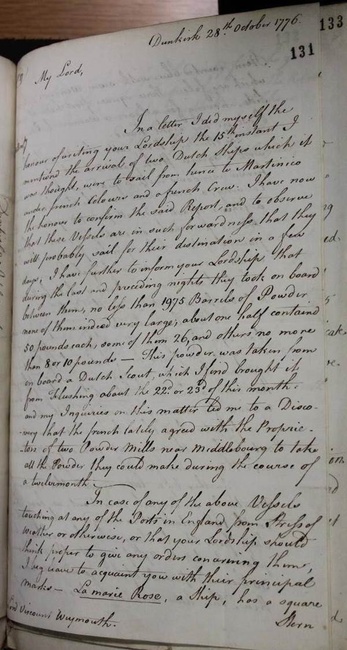

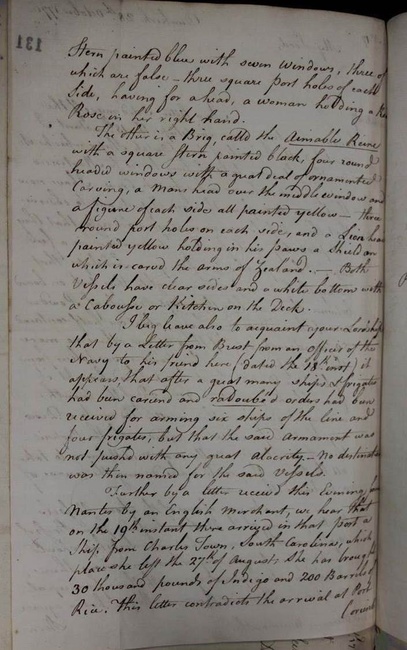

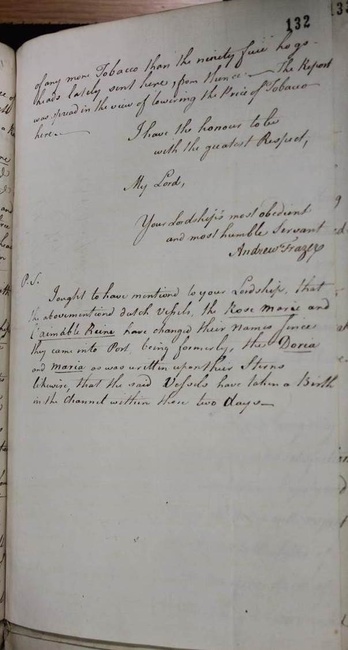

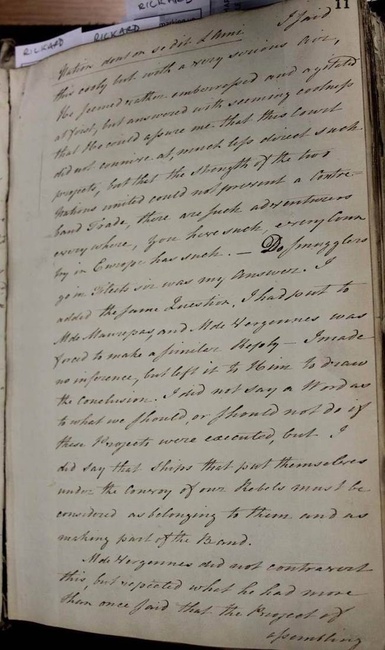

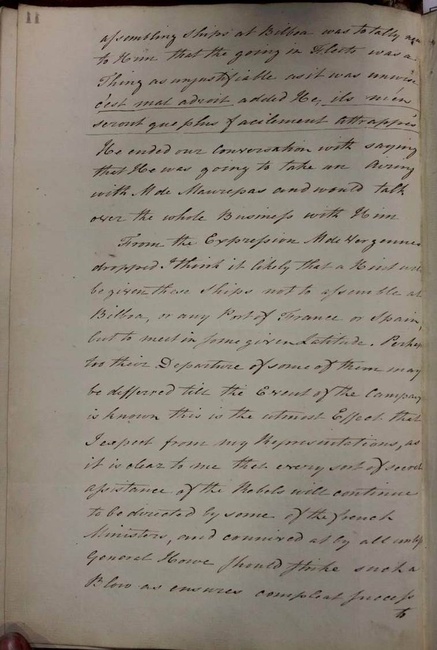

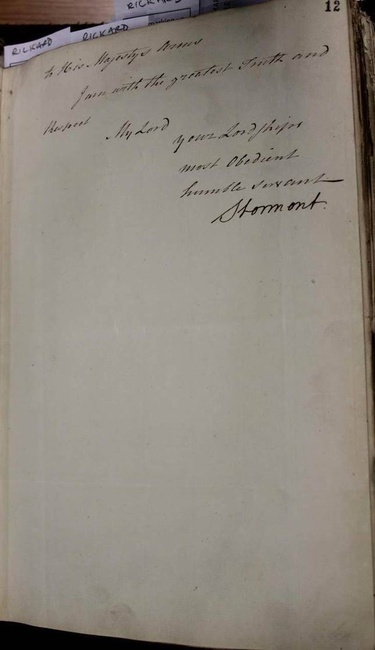

The American patriots began soliciting French support in 1774. The British were working to discourage French support of the Americans. British Ambassadors were at Versailles trying to secure support while British spies were at French ports reporting on the movement of cargo and ships.

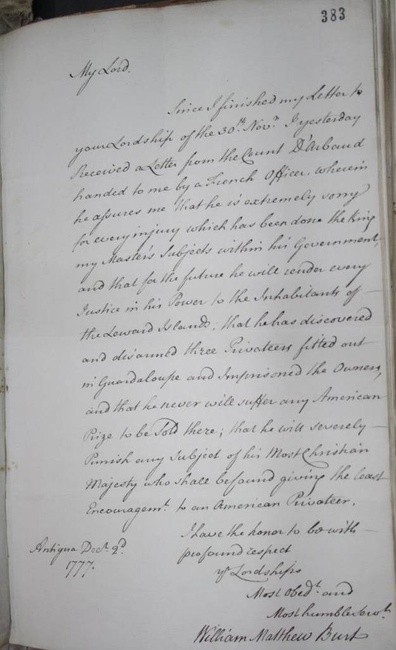

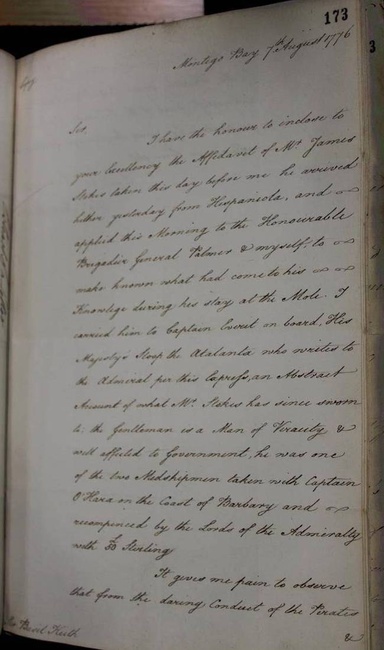

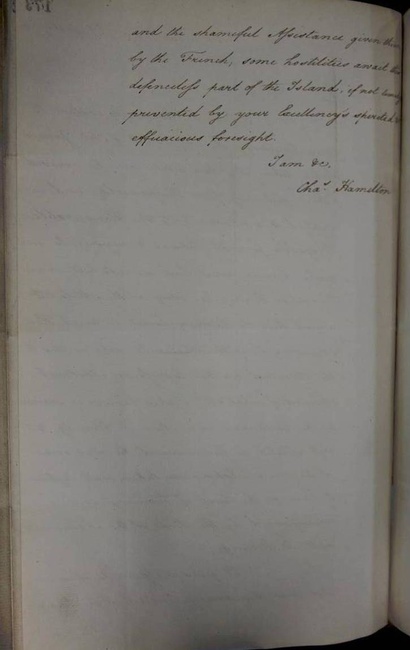

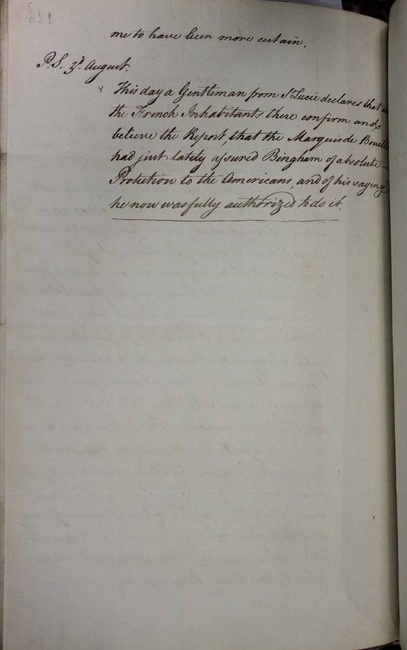

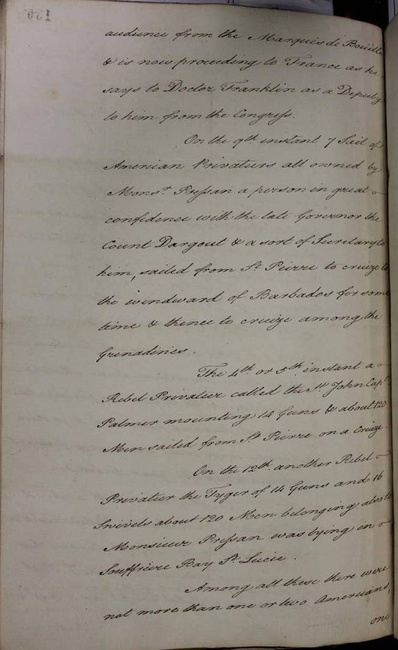

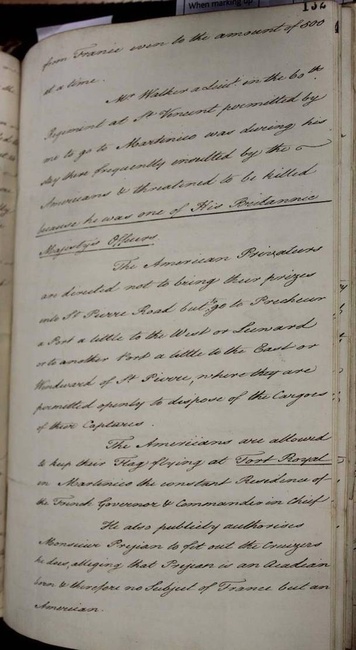

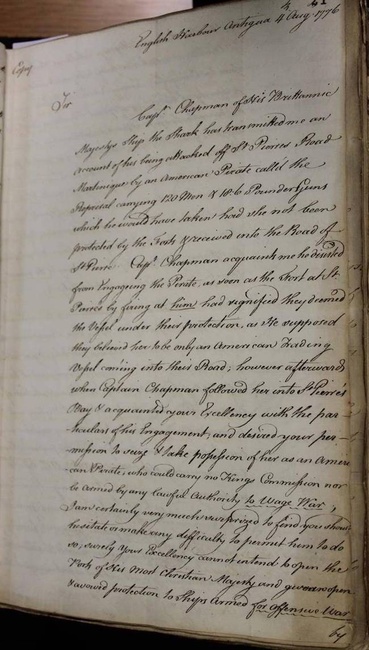

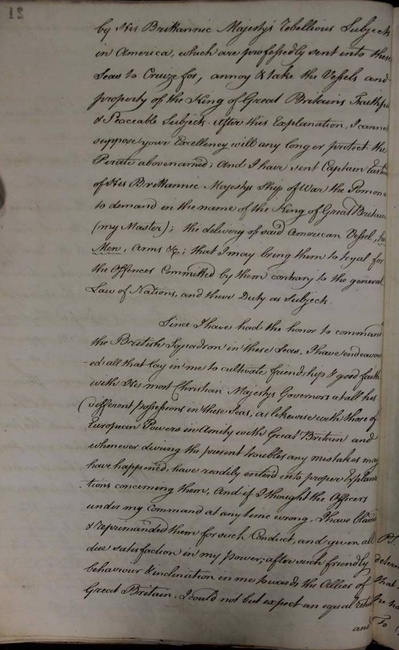

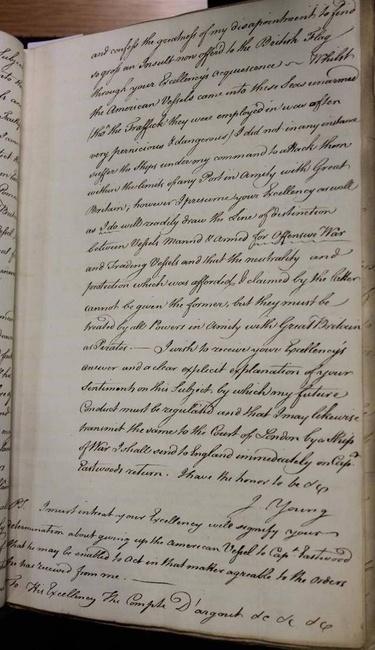

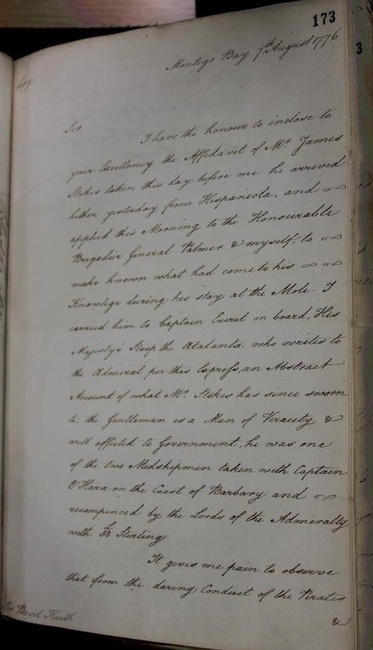

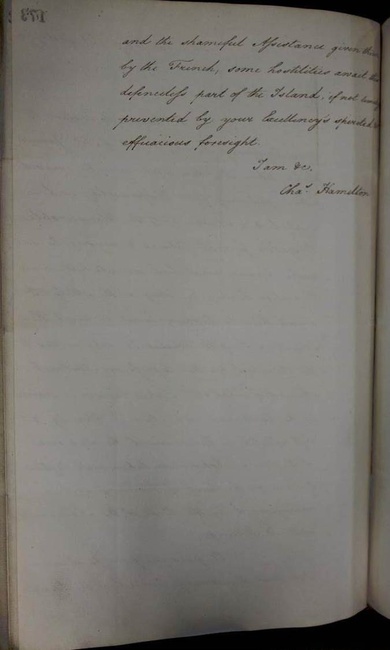

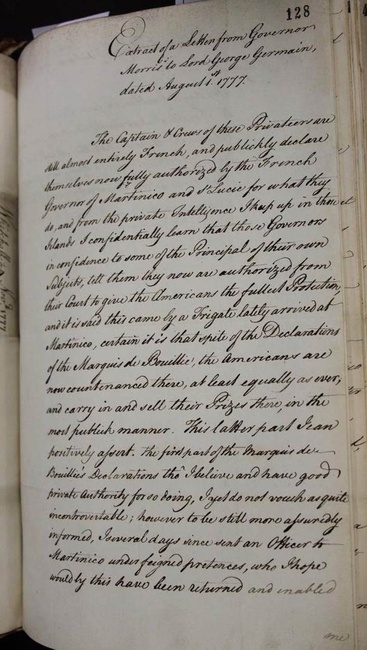

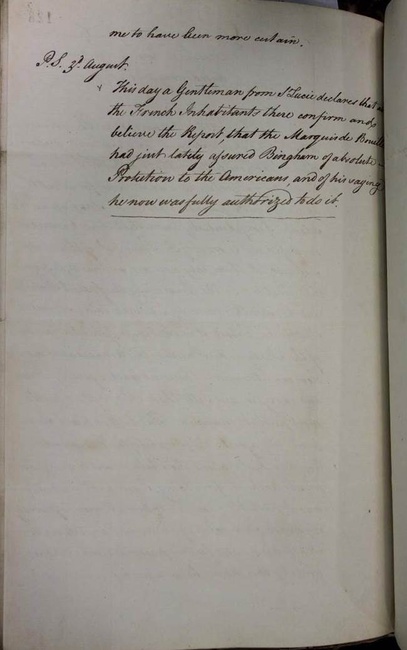

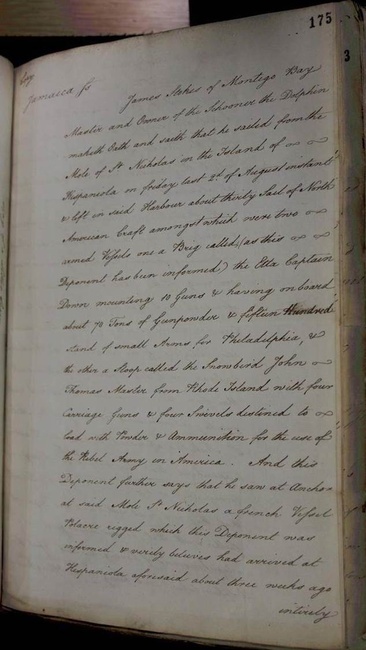

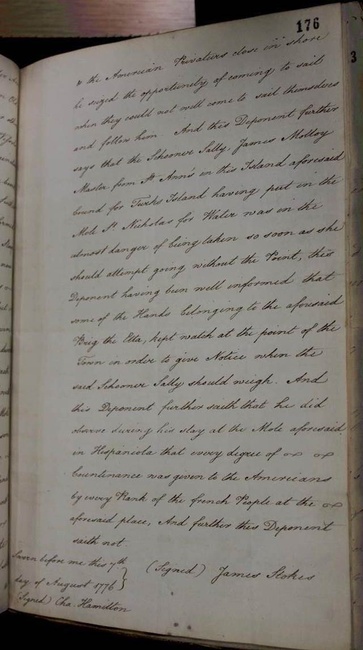

The governors of French colonies were providing support to American privateers or at least turning a blind eye to the selling of illicit goods. Trade ships would leave France with consumer goods and weapons bound for the Caribbean which provided a neutral location for the illicit trade. In addition, French Caribbean towns allowed British cargo ships seized by American rebels to sell their goods in their ports.

Private French citizens volunteered to fight for the Americans as early as 1777. France’s support of the American Revolution became official with “Treaty of Alliance” signed February 6, 1778.

France’s motive for joining the war was not revolutionary. It was the age old motive of revenge for the 1756-1763 French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War).

The Spanish loss of valuable land during the Seven Years’ War provided a motive to join the fight with the Americans (Considering). With hopes of regaining their land in Florida, the Spanish loaned money to Americans and smuggled goods through Havana and the French port of New Orleans. Another motive was a reaction to the Portuguese alliance with Great Britain. Spain negotiated the Treaty of Aranjuez with France to formally enter the war in 1779.

The Dutch became involved in the American Revolution with the motives of revenge and profit. Long-time trading partners with Great Britain, the Dutch experienced a decline in trade and prestige which led to a disagreement over trade rights during war. Extensive trade was conducted with the Americans in the Dutch colony St. Eustatius. In 1776, the St. Eustatius governor was the first foreign power to officially salute the American flag.

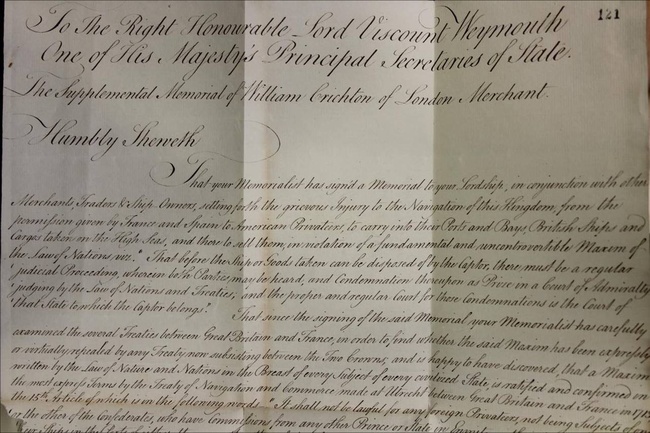

While fighting a war is an expensive endeavor for the hostile nations, a profit is a by-product of a well-designed alliance. The profit generated by conducting business with the American privateers served as an incentive for the Dutch, the French and British citizens in the Caribbean colonies.

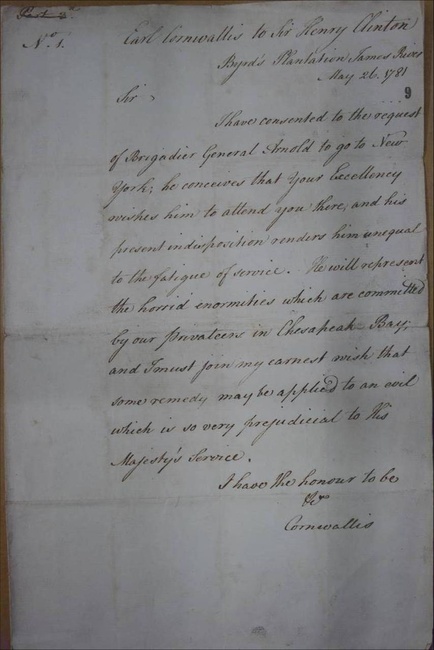

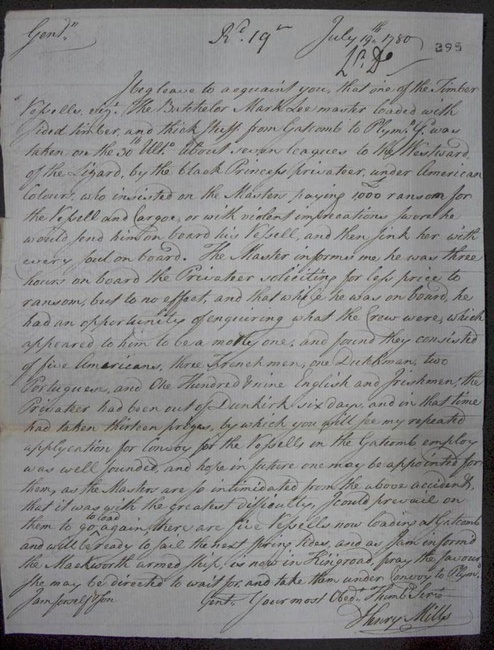

Privateers were commissioned by the Continental Congress. Letters of Marque (permission to raid ships) were issued to ship captains after a bond was posted (Stock). All prizes were reviewed by an admiralty court to ensure the ship was taken according the laws and regulations of the sea. The profits from captured goods were split between the Continental Congress, the sailors and the investors. “Their function was to disrupt British trade, keep American coastal trade open, transport troops, and gather military and other supplies”(Stock). The privateers typically sailed small, maneuverable vessels designed for raiding. Since their goal was to take cargo ships rather than engage warships.

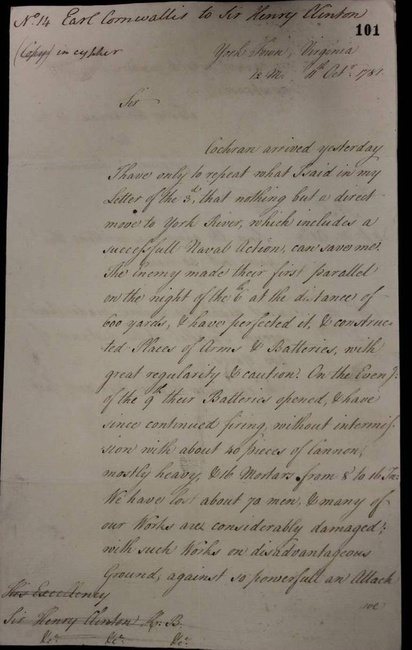

The Continental Navy and the privateers were considered as pirates by the British. The British did not recognize the sovereignty of the United Colonies therefore the Letters of Marque were not considered to be legal. The sailors were not given the rights of prisoners of war; rather they were treated as criminals. The British typically imprisoned the sailors on prison boats rather than hang them as pirates.

While the privateers are not considered to have directly contributed to the American victory in the Revolution they did play a crucial role in securing trade and protecting the coast. The privateers captured of approximately 600 British cargo vessels, costing Great Britain about eighteen million pounds ($302 million). The supplies captured and the profit from selling the goods helped fund the war. The actions of the privateers resulted in the significant increase in shipping insurance and contributed to the loss of support for the British to continue the war.

Lesson & Activities

Bibliography

Brackemyre, Ted. "The American Revolution: A Very European Ordeal." U.S. History Scene. N.p., 2015. Web. 22 Aug. 2015. <ushistoryscene.com>.

U.S. History Scene is an open source website which focuses on teaching American history in a global context, topics cover from slavery to Levittowns. The lesson on the American Revolution discusses the war in context of imperialism and the effect on Europe.

"Considering Independence, Political Envoys, and Aid." The American Revolution. Woodbridge, CT: Primary Source Media, 1999. American Journey. Student Resources in Context. Web. 15 Apr. 2015.

The struggles of a new nation trying to secure alliances to finance their revolution are explored in this article. American diplomats are dispatched to France to meet with Count Charles Gravier de Vergennes, an advisor to King Louis XVI. The various motives of France are mentioned as well as the alliance which France arranges with Spain.

Frayler, John. "Stories

from the Revolution: Privateers in the American Revolution." The

American Revolution: Lighting Freedom's Flame. National Park Service, 4

Dec. 2008. Web. 22 Aug. 2015.

<http://www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/privateers.html>.

The short article would be a good overview of the role of privateers in the Revolution. The article is part of series on the American Revolution which includes a variety of Revolution topics, links and educational resources.

“John Paul Jones.” DISCovering

Biography. Detroit: Gale, 2003. Student Resources in Context. Web.

22 Aug 2015

John Paul Jones was a prolific privateer during the American Revolution. He was considered a hero by American history and a criminal by the British. Jones’ adventures could serve as a high interest hook or a research topic for enrichment.

Maclay, Edgar Stanton. A History of American Privateers. New York: D. Appleton, 1899. Print.

An early book

written about the contributions of privateers is available as an e-book. The

book examines the contributions of privateers in the late 18th and

early 19th century wars.

McGrath, Tim. Give Me a Fast Ship: The Continental Navy and America’s Revolution at Sea. New York: New Caliber, 2014. Print.

Creating a Continental Navy was a hotly debate topic in the Continental Congress. This book follows the politics of creating a navy and authorizing privateers. The story continues with the logistics of acquiring ships, naming captains and securing supplies.

Naval Documents of The American Revolution. Washington: US Government Print. Office, 1966. Naval Documents of the American Revolution. Naval History and Heritage Command, 8 June 2015. Web. 22 Aug. 2015. <http://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/naval-documents-of-the-american-revolution.html>.

A 12-volume work with transcribed primary source documents from 1774-1778 is a rare resource which demonstrates the value of the Continental Navy. Letters involving Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, various ship captains, the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, George Washington, etc. The collection also includes some drawings of ship types and battles.

“The United States and Privateers.” Pirates Through the Ages Reference Library. Ed. Jennifer Stock. Vol. 2: Almanac. Detroit: UXL, 2011. 137-155 Student Resources in Context. Web. 22 Aug 2015.

The article provides an overview the role of the privateers in context of their military value. The role of the privateers was to supplement the Continental Navy, acquire supplies and disrupt British trade.

Wharton, Francis. The Revolutionary Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States. Washington: Government Print. Office, 1889. Online.

This is six volume compilation of letters between diplomats during the American Revolution. The correspondence includes Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, Count Vergennes, and Arthur Lee. The collection includes many letters written to the Committee of Secret Correspondence. Volume 1 includes excerpts of letters bases on topics such as “Attitude of the United States to Foreign Nations,” and “Attitude of France to the United States.” The collection is available through the Library of Congress website.

Materials & Resources

Rebels Images

Going Dutch Images

"When We Were British" project summary

PROJECT SUMMARY: "When We Were British" is a curriculum design project that assembled the expertise of middle and secondary level teachers in North Carolina and Virginia, secondary level teachers in the United Kingdom, university scholars, and public archivists to explore the themes and threads between early America and British histories. This team is collecting, curating, and visualizing digital assets from the National Archives (UK) that explore key themes of British impact and influence in the development of Early America. Once assembled, these documents will be visualized using geoliteracy concepts – and supported with instructional design approaches.

PROJECT GOALS: The final result is set of a teacher-created materials on how to use the National Archives materials in an inquiry-based classroom with an emphasis on the following:

– Geoliteracy in the classroom

– Interdisciplinary approaches that support C3 Framework

– Use of innovative place-based technology

– Elementary, middle, secondary (including AP) instructional models

FUNDING & SUPPORT: Funding was made possible by the joint support of the North Carolina Geographic Alliance and the Virginia Geographic Alliance. Special considerations were given by the National Archives of the United Kingdom.