Chapter 5 - Strangers

Total Video: 01:23:07

Introduction

As the transatlantic Age of Enlightenment celebrated the sciences, political philosophy and human rights, the “Great Awakening” served to unite many colonists socially, and challenge some of the radical new truth claims of the Enlightenment. Another unifying force, the increasing frequency with which colonists found themselves caught up in European military struggles was, to them, entirely irksome and tended to alienate colonist from home-lander in ever-increasing measure.

John Locke

Curiously, the Glorious Revolution had occurred at the same time that Englishman John Locke was completing his “Two Treatises of Government.” In the first treatise, Locke systematically attacked the various justifications for divine right rule and absolute monarchy which had been so precious to King James. In the second treatise, Locke theorized that all of humankind once existed in a state of nature apart from civil government. In that state of nature, everyone possessed natural rights to life, liberty, the pursuit of property, punishment, etc. In this “state of nature” nobody was obligated to obey anyone else. However, because living in a state of nature can be, according Locke’s contemporary, Thomas Hobbes, “nasty, brutish and short,” people gathered together to form civil government, in the process surrendering to that government their personal right to punishment and charging that government with the protection of all remaining rights. Finally, Locke argued, should a government fail to secure those remaining rights, the people retained the right—indeed the obligation—to rise up and replace that government.

Video 00:21:09John Locke (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=17698&xtid=33445) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

While Locke claimed in the preface that his treatise was a justification of the recent “Glorious Revolution,” against King James II, it’s far more likely that he had been working on it for at least a decade before the revolution. It is also important to note that Locke’s insistence on the rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of property” was not the selfish, justification of Capitalism of which Locke has since been accused. Rather, Locke, being born and raised in the British Isles where land is scarce, was most likely referring to a right to acquire property to trade for food. As all of the land was claimed, one had to be able to acquire material goods (property) and have a real claim on them in order to exchange them for the necessities of life. When Jefferson referred back to this writing nearly a century later, the situation would be quite different and "the pursuit of property” would be replaced with “the pursuit of happiness.”

Witches

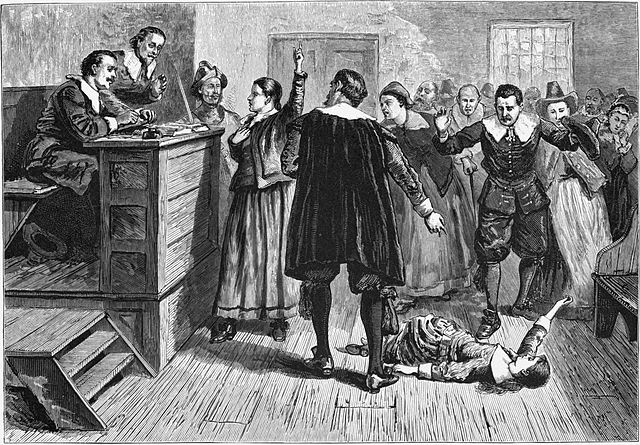

Toward the end of the 1600s, outbreaks of witchcraft, or at least accusations of witchcraft, burned over Europe and Massachusetts. While the apparent epidemic was much wider in Europe, the incidents in Salem, Massachusetts seem to garner the most attention. When, in 1692, several young girls in Salem village began to have convulsive fits without any apparent cause, it was assumed by many that the cause was spiritual. As accusations began to fly, the epidemic worsened, with more seemingly afflicted and more accusations following. In the end, nineteen of the accused were hanged and one crushed, for "engaging in witchcraft."

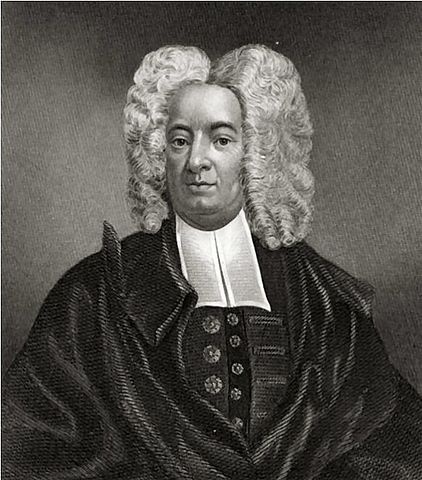

Just what really happened is difficult to say. There were underlying disputes between the people of Salem which could have accounted for who was accused. What remains a mystery is why the erratic behavior occurred in the first place. Various explanations range from actual witchcraft to ergot—a fungus which attaches itself to grain and causes the sort of behaviors described in these incidents. Whatever the “why” of the matter, it ended as quickly as it began when, in October of that same year, the highly respected reverend Increase Mather published a document in which he exhorted that it would be “better that Ten Suspected Witches escape, than that one Innocent Person should be Condemned.”

Even more revealing is a closer analysis of the identities of the accused and the accusers. Salem Village, as much of colonial New England, was undergoing an economic and political transition from a largely agrarian, Puritan-dominated community to a more commercial, secular society. Many of the accusers were representatives of a traditional way of life tied to farming and the church, whereas a number of the accused witches were members of a rising commercial class of small shopkeepers and tradesmen. Salem’s obscure struggle for social and political power between older traditional groups and a newer commercial class was one repeated in communities throughout American history. It took a bizarre and deadly detour when Salem's citizens were swept up by the conviction that the devil was loose in their homes.

The Salem witch trials also serve as a dramatic parable of the deadly consequences of making sensational, but false, charges. Three hundred years later, we still call false accusations against a large number of people a “witch hunt.”

Pirates

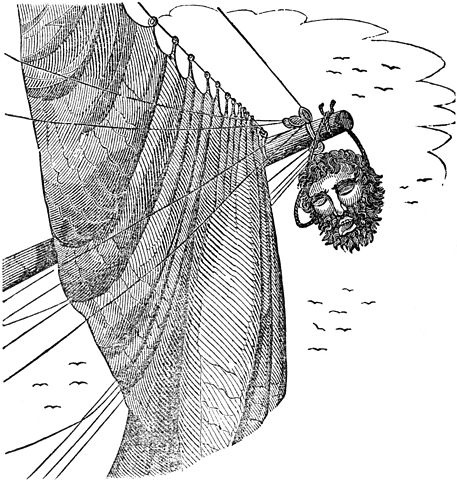

Pirates had been a constant presence in the New World since the Spanish began sailing treasure ships through the Caribbean and home to Spain. But the second half of the 1600s and early 1700s was the heyday of Caribbean Pirates—the most infamous of whom was Edward Teach, also known as, Blackbeard. Blackbeard preyed upon the Caribbean and North American coastal regions, at one point plundering the shipping of Charleston Harbor in South Carolina so effectively that vessels simply quit coming and going to Charleston. Blackbeard was reported to have tied and burned bundles of hemp in his long beard for the added fear it produced in his victims.

Blackbeard was finally dispatched in 1718 when, after being blown nearly to oblivion and boarded by the pirate and his men, HMS Ranger produced hidden seamen from below decks who shot, slashed, stabbed and decapitated him. Blackbeard’s head was hung from the bowsprit and later placed on a pike.

Video 00:03:23 Video “Pirates”(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Nk5b6JPn)

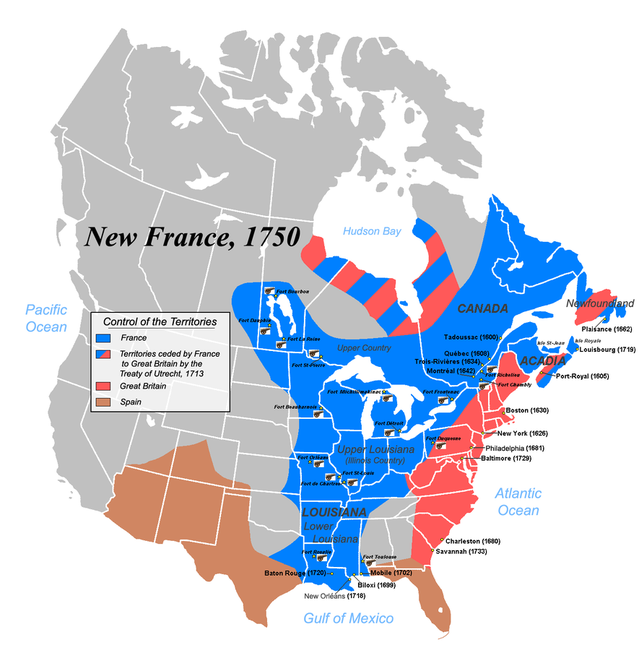

Anglo/French Rivalry

During the fifteen and sixteen hundreds, Spain had been the power to be feared. From the English perspective, not only was Spain bolstered by shiploads of silver and gold from the New World, but they were Catholic as well. By the late 1600s, however, New World mines were drying up and Spain had not invested in any sort of meaningful trade relationships. For example, The English could trade New World tobacco and cotton for Spanish gold. The French could trade fur for Spanish gold. Once the gold mines dried up, the Spanish gold was in circulation and Spain had nothing with which to reacquire it. This left France as the nearest, most formidable and rising competitor, economically and religiously, to England.

King William’s War

In 1689, French fur interests west of the Appalachians, and New England fur interests east of the Appalachians, finally clashed. An alliance between New Englanders and Iroquois ultimately fought the French and their numerous Indian allies to a standstill in 1697 when all boundaries reverted to pre-war status.

Video 00:03:29 Video River of Money(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/w8QKp9g3)

Queen Anne’s War

In 1702, England and France clashed again—this time over the possible succession of a French king to the Spanish throne, thereby creating the possibility of these two catholic empires joining in a powerful coalition. While this war was fought primarily in Europe and on the high seas, it also saw bloody French/Indian raids on the Maine and Massachusetts frontiers. In 1713, the Peace of Utrecht saw Newfoundland, Acadia and Hudson Bay transferred to the British while Spain and France agreed upon a the legitimacy of a protestant royal succession in England.

King George’s War

In 1740, yet another conflict arose between England and France in the Caribbean. Though hardly more than a footnote because the war ended in all gains being returned to each party, this war was the prelude to the deciding struggle for empire between France and England—The French and Indian War.

In each of the wars for empire, English colonists were victims, combatants and often befuddled spectators, who could do little to affect their own fortunes in what they considered their own land.

Video 00:03:23 Video “Different Colonists”(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Nk5b6JPn)

Colonial Growth and Values

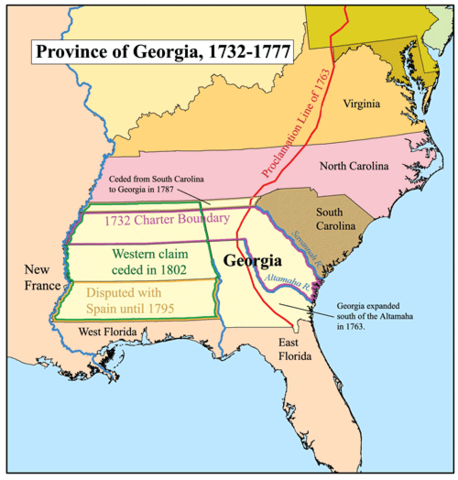

As previously mentioned, the last British colony of Georgia was established in 1732. Perhaps it is a testament to the disdain held by Englishman toward American colonists that English jails were emptied to populate this colony. Incidentally, Georgia was to serve as a buffer against Spanish Florida. It may just as well be a testament to the unrealistic English expectations of colonial loyalty, affection, and obedience that, though populated with criminals, Georgia's charter expressly forbade liquor and slavery—both of which were firmly established in the new colony within twenty years anyway.

Growth

By 1760, approximately one and one-half million persons inhabited the original thirteen colonies. By this time, a substantial number of Germans had populated the interior of the middle colonies like Pennsylvania, while Scots and Irish moved in substantial numbers to both Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Protestant French refugees were found in New York and the Carolinas. Most, however, were English and all would speak English within a generation.

Colonial Ways of Being in the North

By the mid 1700s, distinct patterns of existence had materialized in British North America, with the major differences found between the northern and southern colonies. In the North were found family farms in which the necessities of life were produced, with the surplus going to market. In Northern villages and towns, indentured servitude had long been replaced by apprenticeship in which a servant/apprentice usually grew up locally and was apprenticed to a neighbor to learn a trade. In fact, apprentices often married the master’s daughter, thereby further cementing community bonds.

Colonial Ways of Being in the South

In the South, cash-crops of cotton, rice and tobacco were produced by slave labor on large-scale plantations. Poor White farmers focused on necessary foodstuffs and hoped to one day own slaves. Unlike the North, where villages were taxed for the purpose of public education, no such taxes were levied in the South. Consequently, education was restricted to the wealthy few.

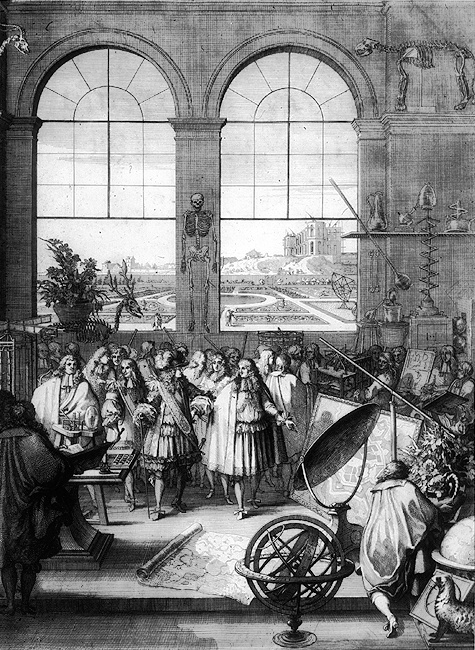

The American Enlightenment

The American Enlightenment came on the heels of the Scientific Revolution and was concurrent with the European Enlightenment. In the 1600s, Sir Francis Bacon’s “scientific method” catapulted scientific inquiry to center stage in Western Civilization. This method was simply to observe a phenomenon, theorize regarding what had been observed, then test the theory to see if the phenomena could be reproduced. This method would revolutionize, and in many cases create, the sciences. Most importantly, it would raise questions about the nature and source of Truth both in Europe and in North America.

Discovery or Revelation

Until the Enlightenment, all truth (about life, the universe, and everything else) had been widely understood as that which was revealed by God, especially through the Bible. The scientific method, however, caused a widespread rethinking of the nature of truth. Could truth be discovered as well as revealed? Must truth come only from discovery, or only from revelation?

The fledgling scientific community quickly began gravitating toward only accepting truth which was purely discoverable. Citing the history of violence inflicted by and on behalf of religion (which never seemed to uncover new Truth like science did), many scientific thinkers began to describe God as a sort of clock-maker who wound up the universe and then walked away (a concept known as Deism). Some then abandoned all notions of God and opted for a purely material universe with purely material explanations for everything that happens ( known today as Materialism).

Video (00:11:00) A Reformation of the Mind (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/play/8THGFK) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

What was at Stake?

For the colonial descendants of the Puritan Fathers, an entire worldview was at stake. In a purely material universe, freedom of choice is not possible. Everything, from exploding stars to baptism, would be pre-determined by random matter colliding and interacting at the chemical, celestial and other levels—with no choice involved. One problem was that such a material explanation actually fit with the Puritan view of predestination in which all persons were “predetermined’ for heaven or hell, with nothing at all possible to change that outcome. What ‘was’ possible was to seek “evidence” of predestination by “observing” whether a person’s life, occupation and actions were blessed or not. As Puritans and others grappled with this issue, Puritan liturgy stagnated and became dry, terse, “reasonable” and...boring.

Society, Schools and Culture

In the 18th century, the intellectual and cultural development of Pennsylvania reflected, in large measure, the vigorous personalities of two men: James Logan and Benjamin Franklin. Logan was secretary of the colony, and it was in his fine library that young Franklin found the latest scientific works. In 1745 Logan erected a building for his collection and bequeathed both building and books to the city.

Franklin contributed even more to the intellectual activity of Philadelphia. He formed a debating club that became the embryo of the American Philosophical Society. His endeavors also led to the founding of a public academy that later developed into the University of Pennsylvania. He was a prime mover in the establishment of a subscription library, which he called “the mother of all North American subscription libraries.”

In the Southern colonies, wealthy planters and merchants imported private tutors from Ireland or Scotland to teach their children. Some sent their children to school in England. Having these other opportunities, the upper classes in the Tidewater were not interested in supporting public education. In addition, the diffusion of farms and plantations made the formation of community schools difficult. There were only a few free schools in Virginia.

The desire for learning did not stop at the borders of established communities, however. On the frontier, the Scots-Irish, though living in primitive cabins, were firm devotees of scholarship, and they made great efforts to attract learned ministers to their settlements.

Literary production in the colonies was largely confined to New England. Here attention concentrated on religious subjects. Sermons were the most common products of the press. A famous Puritan minister, the Reverend Cotton Mather, wrote some 400 works. His masterpiece, Magnalia Christi Americana, presented the pageant of New England’s history. The most popular single work of the day was the Reverend Michael Wigglesworth’s long poem, “The Day of Doom,” which described the Last Judgment in terrifying terms.

In 1704 Cambridge, Massachusetts, launched the colonies’ first successful newspaper. By 1745 there were 22 newspapers being published in British North America.

In New York, an important step in establishing the principle of freedom of the press took place with the case of John Peter Zenger, whose New York Weekly Journal, begun in 1733, represented the opposition to the government. After two years of publication, the colonial governor could no longer tolerate Zenger’s satirical barbs, and had him thrown into prison on a charge of seditious libel. Zenger continued to edit his paper from jail during his nine month trial, which excited intense interest throughout the colonies. Andrew Hamilton, the prominent lawyer who defended Zenger, argued that the charges printed by Zenger were true and hence not libelous. The jury returned a verdict of not guilty, and Zenger went free.

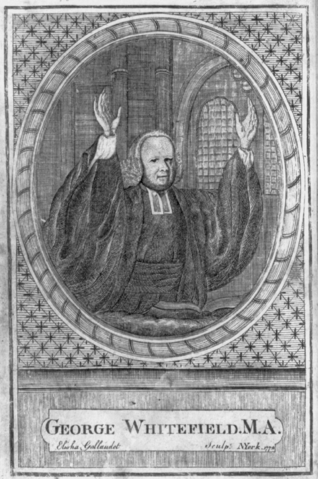

The Great Awakening

The increasing prosperity of the towns prompted fears that the devil was luring society into pursuit of worldly gain and may have contributed to the religious reaction of the 1730s, known as the Great Awakening which challenged both Scientific and Puritan thinking. George Whitefield, a Wesleyan revivalist who arrived from England in 1739, brought with him a new style of preaching, which was flamboyant (by comparison to stiff Puritan sermons), drew immense crowds of 20,000 or more, and served to give a sense of unity to the colonists. When Whitefield would address a crowd in Virginia, for example, he might inform the crowd that they were just like their brethren in Massachusetts in their response to his message.

Edwards

Jonathan Edwards was the most prominent of those influenced by Whitefield and the Great Awakening. His most memorable contribution was his 1741 sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Rejecting theatrics, he delivered his message in a quiet, thoughtful manner, arguing that the established churches sought to deprive Christianity of its function of redemption from sin. His magnum opus, Of Freedom of Will (1754), attempted to reconcile Calvinism with the Enlightenment. As Puritans, Deists, and the non-religious criticized the “enthusiastic” gatherings of the Awakening, Edwards, who served the Congregational Church in Northampton, Massachusetts, used scientific reasoning to defend them. Edwards agreed that passion and strange behavior were not evidence of spiritual substance. However, Edwards argued, a changed life was. Indeed, the multitude of changed lives which resulted seemed to satisfy the scientific need for “material” evidence and results while allowing the “immaterial” to remain a viable part of the American experience. Religious turmoil swept throughout New England and the middle colonies as ministers left established churches to preach the revival.

In the South

In the South, slaveholders had initially tried to keep Christianity mysterious and incomprehensible to slaves. In question was whether slaves had souls and whether they could (or should) be perceived as “brothers and sisters in Christ.” Southern preachers, whose salaries were controlled by local congregations, found that affirming such biblical notions was a quick road to unemployment and poverty. By the time of the Great Awakening, however, Baptists virtually stormed the southern colonies and encouraged blacks to participate in the open air meetings. A struggling Black Christian community found new fire and increasingly identified with the Awakening and the biblical book of Exodus in which Moses led the enslaved Israelites to freedom in the “promised land.”

The Great Awakening gave rise to evangelical denominations (those Christian churches that believe in personal conversion and the inerrancy of the Bible) and the spirit of revivalism, which continue to play significant roles in American religious and cultural life. It weakened the status of the established clergy and provoked believers to rely on their own conscience. Perhaps most important, it led to the proliferation of sects and denominations, which in turn encouraged general acceptance of the principle of religious toleration.

Recap of the Emergence of Colonial Government

In the early phases of colonial development, a striking feature was the lack of controlling influence by the English government. All colonies except Georgia emerged as companies of shareholders, or as feudal proprietorships stemming from charters granted by the Crown. The fact that the king had transferred his immediate sovereignty over the New World settlements to stock companies and proprietors did not, of course, mean that the colonists in America were necessarily free of outside control. Under the terms of the Virginia Company charter, for example, full governmental authority was vested in the company itself. Nevertheless, the crown expected that the company would be resident in England. Inhabitants of Virginia, then, would have no more voice in their government than if the king himself had retained absolute rule.

Still, the colonies considered themselves chiefly as commonwealths or states, much like England itself, having only a loose association with the authorities in London. In one way or another, exclusive rule from the outside withered away. The colonists — inheritors of the long English tradition of the struggle for political liberty — incorporated concepts of freedom into Virginia’s first charter. It provided that English colonists were to exercise all liberties, franchises, and immunities “as if they had been abiding and born within this our Realm of England.” They were, then, to enjoy the benefits of the Magna Carta — the charter of English political and civil liberties granted by King John in 1215 — and the common law — the English system of law based on legal precedents and tradition. In 1618 the Virginia Company had issued instructions to its appointed governor providing that free inhabitants of the plantations should elect representatives to join with the governor and an appointive council in passing ordinances for the welfare of the colony.

These measures proved to be some of the most far-reaching in the entire colonial period. From then on, it was generally accepted that the colonists had a right to participate in their own government. In most instances, the king, in making future grants, provided in the charter that the free men of the colony should have a voice in legislation affecting them. Thus, charters awarded to the Calverts in Maryland, William Penn in Pennsylvania, the proprietors in North and South Carolina, and the proprietors in New Jersey specified that legislation should be enacted with “the consent of the freemen.”

In New England, for many years, there was even more complete self government than in the other colonies. Aboard the Mayflower, the Pilgrims had adopted the “Mayflower Compact,” to “combine ourselves together into a civil body politic for our better ordering and preservation … and by virtue hereof [to] enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices ... as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony. ...”

Although there was no legal basis for the Pilgrims to establish a system of self-government, the action was not contested, and, under the compact, the Plymouth settlers were able for many years to conduct their own affairs without outside interference.

A similar situation had developed in the Massachusetts Bay Company, which had been given the right to govern itself. Thus, full authority rested in the hands of persons residing in the colony. At first, the dozen or so original members of the company who had come to America attempted to rule autocratically. But the other colonists soon demanded a voice in public affairs and indicated that refusal would lead to a mass migration.

As company members yielded, control of the government passed to elected representatives. Subsequently, other New England colonies — such as Connecticut and Rhode Island — also succeeded in becoming self-governing simply by asserting that they were beyond any governmental authority, and then setting up their own political system modeled after that of the Pilgrims at Plymouth.

In only two cases was the self-government provision omitted. These were New York, which was granted to Charles II’s brother, the Duke of York (later to become King James II), and Georgia, which was granted to a group of “trustees.” In both instances the provisions for governance were short-lived, for the colonists demanded legislative representation so insistently that the authorities soon yielded.

In the mid-17th century, the English were too distracted by their Civil War (1642-49) and Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan Commonwealth to pursue an effective colonial policy. After the restoration of Charles II and the Stuart dynasty in 1660, England had more opportunity to attend to colonial administration. Even then, however, it was inefficient and lacked a coherent plan. The colonies were left largely to their own devices.

The remoteness afforded by a vast ocean also made control of the colonies difficult. Added to this was the character of life itself in early America. From countries limited in space and dotted with populous towns, the settlers had come to a land of seemingly unending reach. On such a continent, natural conditions promoted a tough individualism, as people became used to making their own decisions. Government penetrated the backcountry only slowly, and conditions of anarchy often prevailed on the frontier.

Yet the assumption of self-government in the colonies did not go entirely unchallenged. In the 1670s, the Lords of Trade and Plantations, a royal committee established to enforce the mercantile system in the colonies, had moved to annul the Massachusetts Bay charter because the colony was resisting the government’s economic policy. James II in 1685 approved a proposal to create a Dominion of New England and place colonies south through New Jersey under its jurisdiction, thereby tightening the Crown’s control over the whole region. The royal governor, Sir Edmund Andros, levied taxes by executive order, implemented a number of other harsh measures, and jailed those who resisted.

When news of the Glorious Revolution (1688-89), which deposed James II in England, reached Boston, the population rebelled and imprisoned Andros. Under a new charter, Massachusetts and Plymouth were united for the first time in 1691 as the royal colony of Massachusetts Bay. The other New England colonies quickly reinstalled their previous governments.

The English Bill of Rights and the Toleration Act of 1689 affirmed freedom of worship for Christians in the colonies as well as in England and enforced limits on the Crown. Equally important, John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government (1690), which was viewed as the Glorious Revolution’s major theoretical justification, set forth a theory of government based not on divine right but on contract. It contended that the people, endowed with natural rights of life, liberty, and property, had the right to rebel when governments violated their rights.

By the early 18th century, almost all the colonies had been brought under the direct jurisdiction of the British Crown, but under the rules established by the Glorious Revolution. Colonial governors sought to exercise powers that the king had lost in England, but the colonial assemblies, aware of events there, attempted to assert their “rights” and “liberties.” Their leverage rested on two significant powers similar to those held by the English Parliament: the right to vote on taxes and expenditures, and the right to initiate legislation rather than merely react to proposals of the governor.

The legislatures used these rights to check the power of royal governors and to pass other measures to expand their power and influence. The recurring clashes between governor and assembly made colonial politics tumultuous and worked increasingly to awaken the colonists to the divergence between American and English interests. In many cases, the royal authorities did not understand the importance of what the colonial assemblies were doing and simply neglected them. Nonetheless, the precedents and principles established in the conflicts between assemblies and governors eventually became part of the unwritten “constitution” of the colonies. In this way, the colonial legislatures asserted the right of self-government.

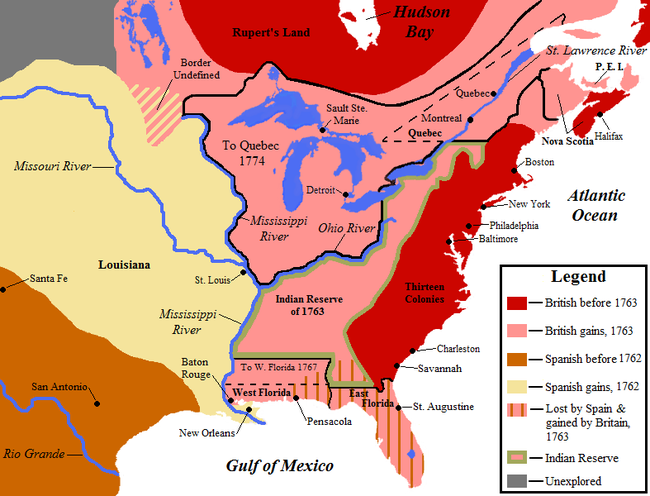

THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR

France and Britain engaged in a succession of wars in Europe and the Caribbean throughout the 18th century. Though Britain secured certain advantages — primarily in the sugar-rich islands of the Caribbean — the struggles were generally indecisive, and France remained in a powerful position in North America. By 1754, France still had a strong relationship with a number of Native American tribes in Canada and along the Great Lakes. It controlled the Mississippi River and, by establishing a line of forts and trading posts, had marked out a great crescent- shaped empire stretching from Quebec to New Orleans. The British remained confined to the narrow belt east of the Appalachian Mountains. Thus the French threatened not only the British Empire but also the American colonists themselves, for in holding the Mississippi Valley, France could limit their westward expansion.

An armed clash took place in 1754 at Fort Duquesne, the site where Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is now located, between a band of French regulars and Virginia militiamen under the command of 22-year-old George Washington, a Virginia planter and surveyor. The British government attempted to deal with the conflict by calling a meeting of representatives from New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and the New England colonies. From June 19 to July 10, 1754, the Albany Congress, as it came to be known, met with the Iroquois in Albany, New York, in order to improve relations with them and secure their loyalty to the British.

But the delegates also declared a union of the American colonies “absolutely necessary for their preservation” and adopted a proposal drafted by Benjamin Franklin. The Albany Plan of Union provided for a president appointed by the king and a grand council of delegates chosen by the assemblies, with each colony to be represented in proportion to its financial contributions to the general treasury. This body would have charge of defense, Native American relations, and trade and settlement of the west. Most importantly, it would have independent authority to levy taxes. But none of the colonies accepted the plan, since they were not prepared to surrender either the power of taxation or control over the development of the western lands to a central authority.

Video: 00:32:00 Washington the Warrior (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/play/RVJFWK) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

In spite of their more numerous victories and more numerous Indian allies, the French would be defeated by both the Winter and the Royal Navy, both of which succeeded in blocking French resupply ships to the Saint Lawrence River and New Orleans respectively. Though the war was fought in Europe, on the high seas, and North America, the English concentrated on the North American theater, correctly perceiving that North America was where the future would lie.

Settlement

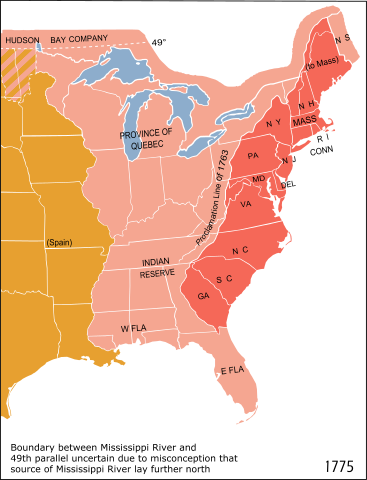

In 1763, the Peace of Paris granted all of Canada and all claims east of the Mississippi River to the British. The British also obtained Spanish Florida and, in a stunning turn of events, the French transferred by secret treaty, all of French Louisiana to Spain. The French were out of North America entirely—exactly what the British had hoped for.

Problems of Administration

Having triumphed over France, Britain was now compelled to face a problem that it had hitherto neglected, the governance of its empire. London thought it essential to organize its now vast possessions to facilitate defense, reconcile the divergent interests of different areas and peoples, and distribute more evenly the cost of imperial administration.

In North America alone, British territories had more than doubled. A population that had been predominantly Protestant and English now included French-speaking Catholics from Quebec, and large numbers of partly Christianized Native Americans. Defense and administration of the new territories, as well as of the old, would require huge sums of money and increased personnel. The old colonial system was obviously inadequate to these tasks. Measures to establish a new one, however, would rouse the latent suspicions of colonials who increasingly would see Britain as no longer a protector of their rights, but rather a danger to them.

An Exceptional Nation?

The United States of America did not emerge as a nation until about 175 years after its establishment as a group of mostly British colonies. Yet from the beginning it was a different society in the eyes of many Europeans who viewed it from afar, whether with hope or apprehension. Most of its settlers — whether the younger sons of aristocrats, religious dissenters, or impoverished indentured servants — came there lured by a promise of opportunity or freedom not available in the Old World. The first Americans were reborn free, establishing themselves in a wilderness unencumbered by any social order other than that of the aboriginal peoples they displaced. Having left the baggage of a feudal order behind them, they faced few obstacles to the development of a society built on the principles of political and social liberalism that emerged with difficulty in 17th- and 18th-century Europe. Based on the thinking of the philosopher John Locke, this sort of liberalism emphasized the rights of the individual and constraints on government power.

Most immigrants to America came from the British Isles, the most liberal of the European polities along with The Netherlands. In religion, the majority adhered to various forms of Calvinism with its emphases on both divine and secular contractual relationships. These greatly facilitated the emergence of a social order built on individual rights and social mobility. The development of a more complex and highly structured commercial society in coastal cities by the mid-18th century did not stunt this trend; it was in these cities that the American Revolution was made. The constant reconstruction of society along an ever-receding Western frontier equally contributed to a liberal-democratic spirit.

In Europe, ideals of individual rights advanced slowly and unevenly; the concept of democracy was even more alien. The attempt to establish both in continental Europe’s oldest nation would lead to the French Revolution. The effort to destroy a neofeudal society while establishing the rights of man and democratic fraternity generated terror, dictatorship, and Napoleonic despotism. In the end, it led to reaction and gave legitimacy to a decadent old order. In America, the European past was overwhelmed by ideals that sprang naturally from the process of building a new society on virgin land. The principles of liberalism and democracy were strong from the beginning. A society that had thrown off the burdens of European history would naturally give birth to a nation that saw itself as exceptional.