Chapter 8 - Early Republic

By U.S. Post Office; Bureau of Engraving and Printing; designed by Charles R. Chickering (U.S. Government, Dept of the Post Office) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Total Video: 01:01:19

Introduction

The early republic developed along uneasy lines. The judicial branch of government was, as yet, untested and effectively powerless. By the time the Civil War broke out, however, the judicial branch of the government would be exerting its influence as an equal player with the executive and legislative branches. Another war with Great Britain would destroy the Federalists and divide the Democratic Republicans into two new and opposing parties. The absurd compromises over slavery between North and South during the Constitutional Convention had been intended to avoid immediate national collapse. Effectively the collapse was merely postponed until the spirit of compromise would be exhausted in the 1850s

Video: (00:04:12) The Republic (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Co69Ngf4&sa=D&ust=1464788700293000&usg=AFQjCNGvEX9O_Et8Bu_hmOhoHF4GfcdaCg

By 1800 the American people were ready for a change. Under Washington and Adams, the Federalists had established a strong government, but sometimes failing to honor the principle that the American government must be responsive to the will of the people, they had followed policies that alienated large groups. For example, in 1798 they had enacted a tax on houses, land, and slaves, affecting every property owner in the country.

The Revolution of 1800

Ultimately Federalist hopes of an official (declared) war against France were dashed when John Adams supported a successful peace commission to France in 1800. Alexander Hamilton, incensed at the loss of this political cash cow, led a split in the Federalist Party which would end Adams’ hope of a second term and hand the presidency to Jefferson. The election of 1800 stands as a monument to American politics and an inspiration to democracies ever since, for this was the first time that power at the very highest level was transferred from one opposing faction to another—without bloodshed.

Video: (00:02:16) John Adams(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Km74Syp2&sa=D&ust=1464788700296000&usg=AFQjCNH4XMS-HzApgvWNHDr_1btOerwprg)

Jefferson had steadily gathered behind him a great mass of small farmers, shopkeepers, and other workers. He won a narrow victory in a closely contested election. Jefferson enjoyed extraordinary favor because of his appeal to American idealism. In his inaugural address, the first such speech in the new capital of Washington, D.C., he promised “a wise and frugal government” that would preserve order among the inhabitants but leave people “otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry, and improvement.”

Video: (00:03:13) The Presidents: Jefferson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=95QRQP) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

Jefferson’s mere presence in the White House encouraged democratic procedures. He preached and practiced democratic simplicity, eschewing much of the pomp and ceremony of the presidency. In line with Republican ideology, he sharply cut military expenditures. Believing America to be a haven for the oppressed, he secured a liberal naturalization law. By the end of his second term, his far-sighted secretary of the treasury, Albert Gallatin, had reduced the national debt to less than $560 million. Widely popular, Jefferson won reelection easily.

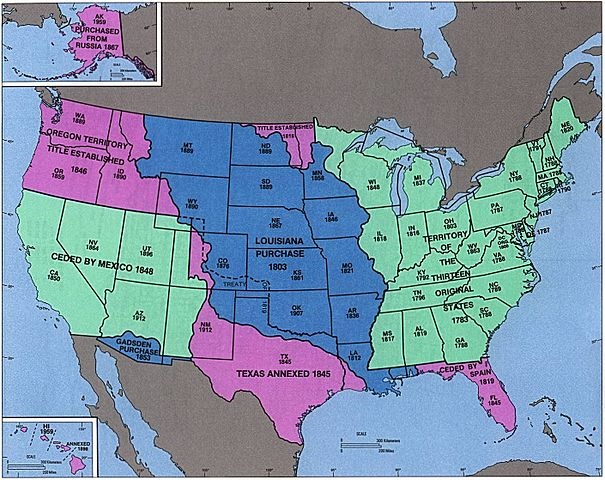

LOUISIANA

![Territory of the Louisiana Purchase

By William Morris [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7573)

Map of the United States showing the region included in the Louisiana Purchase; with the northern border in Alberta and Saskatchewan and stretching southeast to Louisiana. The states of Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas are fully within the boundaries of the purchase. Parts of Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas are also included in the purchase territory.

Thomas Jefferson was Alexander Hamilton’s opposite in nearly every way. Instead of strong central government, Jefferson preferred strong state governments. Instead of the mighty cities and industry preferred by Hamilton, Jefferson wished to see small villages and family farms as the backbone of the economy. Indeed, cities were, for Jefferson, putrid cesspools of humanity—devoid of morality. In fact, it was this vision, which led Jefferson into his own violation of the Constitution when he personally made arrangements with France’s Napoleon Bonaparte for the purchase of French Louisiana.

Video: (00:02:33) Natchez Trace (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Gi9m2MCy&sa=D&ust=1464788700305000&usg=AFQjCNEDoG52ofsyM3gDw13t1OkzeRZtUg)

Though France had ceded the Louisiana territory to Spain by secret treaty in 1763, the administration of the territory proved expensive and difficult. Spanish hopes to bolster Louisiana’s economy literally sank with the treasure ship El Cazador in 1784; the ship had been en route to Louisiana for just that purpose. In 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte reacquired Louisiana in hopes of reestablishing a French empire in North America. The move filled Americans with apprehension and indignation. French plans for a huge colonial empire just west of the United States seriously threatened the future development of the United States. Jefferson asserted that if France took possession of Louisiana, “from that moment we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.”

A failed attempt at putting down a slave revolt in French Haiti along with continuing difficulties at home convinced Napoleon to offer the territory to the United States for fifteen million dollars which would be used to fund his war effort in Europe. In 1803, Jefferson bought it, though the Constitution clearly did not designate such power to the President. The United States obtained the “Louisiana Purchase” for $15 million in 1803. It contained more than a million square miles as well as the port of New Orleans. The nation had gained a sweep of rich plains, mountains, forests, and river systems that within 80 years would become its heartland — and a breadbasket for the world.

Video (00:02:01) El Cazador (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Pr97QoMp&sa=D&ust=1464788700308000&usg=AFQjCNE8xMjNES--yS3moTcv2ubn7HKJCg)

Lewis and Clark

Cries of “unconstitutional” quickly subsided as Americans realized that the size of the United States had just been doubled—and that for a song. Here was the perfect chance for Jefferson to realize his vision of an agricultural America. Jefferson’s personal secretary Meriwether Lewis co-led the expedition to the Pacific Ocean with William Clark. The expedition was to preserve or send biological, geological and other scientific specimens, make friends with any tribes encountered, and look for a navigable water route to the Pacific. They succeeded in all but the latter and returned after about a two year expedition having lost only one of fifty men.

Video: (00:03:29) Pompey’s Pillar (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Ek3i9D2A&sa=D&ust=1464788700311000&usg=AFQjCNGYeW86m97WVmYqmFD5HWwubIKMTQ)

BRITAIN

As Jefferson began his second term in 1805, he declared American neutrality in the struggle between Great Britain and France. Although both sides sought to restrict neutral shipping to the other, British control of the seas made its interdiction and seizure much more serious than any actions by Napoleonic France. British naval commanders routinely searched American ships, seized vessels and cargoes, and took off sailors believed to be British subjects. They also frequently impressed American seamen into their service.

Video: (00:02:31) The Presidents Jefferson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&AssignmentID=QMC2PM) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

When Jefferson issued a proclamation ordering British warships to leave U.S. territorial waters, the British reacted by impressing more sailors. Jefferson then decided to rely on economic pressure; in December 1807 Congress passed the Embargo Act, forbidding all foreign commerce. Ironically, the law required strong police authority that vastly increased the powers of the national government. Economically, it was disastrous. In a single year American exports fell to one-fifth of their former volume. Shipping interests were almost ruined by the measure; discontent rose in New England and New York. Agricultural interests suffered heavily also. Prices dropped drastically when the Southern and Western farmers could not export their surplus grain, cotton, meat, and tobacco.

The embargo failed to starve Great Britain into a change of policy. As the grumbling at home increased, Jefferson turned to a milder measure, which partially conciliated domestic shipping interests. In early 1809 he signed the Non-Intercourse Act permitting commerce with all countries except Britain or France and their dependencies.

James Madison succeeded Jefferson as president in 1809. Relations with Great Britain grew worse, and the two countries moved rapidly toward war. The president laid before Congress a detailed report, showing several thousand instances in which the British had impressed American citizens. In addition, northwestern settlers had suffered from attacks by Indians whom they believed had been incited by British agents in Canada. In turn, many Americans favored conquest of Canada and the elimination of British influence in North America, as well as vengeance for impressment and commercial repression. By 1812, war fervor was dominant. On June 18, the United States declared war on Britain.

Video (00:01:52) The Presidents: Madison (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/play/XVLTGG) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

THE WAR OF 1812

The nation went to war bitterly divided. This time, while the largely Democratic-Republican South and West favored the conflict, Federalist-dominated New York and New England opposed it because it interfered with their commerce. The U.S. military was weak. The army had fewer than 7,000 regular soldiers, distributed in widely scattered posts along the coast, near the Canadian border, and in the remote interior. The state militias were poorly trained and undisciplined.

Hostilities began with an invasion of Canada, which, if properly timed and executed, would have brought united action against Montreal. Instead, the entire campaign miscarried and ended with the British occupation of Detroit. The U.S. Navy, however, scored successes. In addition, American privateers, swarming the Atlantic, captured 500 British vessels during the fall and winter months of 1812 and 1813.

The campaign of 1813 centered on Lake Erie. General William Henry Harrison — who would later become president — led an army of militia, volunteers, and regulars from Kentucky with the object of reconquering Detroit. On September 12, while he was still in upper Ohio, news reached him that Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry had annihilated the British fleet on Lake Erie. Harrison occupied Detroit and pushed into Canada, defeating the fleeing British and their Indian allies on the Thames River. The entire region now came under American control.

![“Battle of Lake Erie” by William Henry Powell [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7586)

Commodore Perry stands, pointing to the right, in a rowboat with with about eight sailors. An American flag waves from the back of the boat. Many larger boats are shown in the distance, obscured by a stormy sky.

![“The Taking of the City of Washington... by the British Forces Under Major General Ross on August 24, 1814” Creator unknown (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7587)

The buildings of Washington are billowing with smoke and flames, while British soldiers are shown brandishing weapons and manning cannons. British soldiers are also seen boats in the foreground, aiming weapons at several boats which are on fire.

A year later Commodore Thomas Macdonough won a point-blank gun duel with a British flotilla on Lake Champlain in upper New York. Deprived of naval support, a British invasion force of 10,000 men retreated to Canada. Nevertheless, the British fleet harassed the Eastern seaboard with orders to “destroy and lay waste.” On the night of August 24, 1814, an expeditionary force routed American militia, marched to Washington, D.C., and left the city in flames. President James Madison fled to Virginia.

British and American negotiators conducted talks in Europe. The British envoys decided to concede, however, when they learned of Macdonough’s victory on Lake Champlain. Faced with the depletion of the British treasury due in large part to the heavy costs of the Napoleonic Wars, the negotiators for Great Britain accepted the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814. It provided for the cessation of hostilities, the restoration of conquests, and a commission to settle boundary disputes. Unaware that a peace treaty had been signed, forces from both sides continued fighting into 1815 near New Orleans, Louisiana. Led by General Andrew Jackson, the United States scored the greatest land victory of the war with the British sustaining over 2,000 casualties to the Americans 71. This ended once and for all any British hopes of reestablishing continental influence south of the Canadian border.

Video: (00:06:01) Battle of New Orleans (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Ds79Jam5&sa=D&ust=1464788700324000&usg=AFQjCNE7xKPJKjKxh3mMa8-3L9EDoDsfdQ)

While the British and Americans were negotiating a settlement, Federalist delegates selected by the legislatures of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, and New Hampshire gathered in Hartford, Connecticut, to express opposition to “Mr. Madison’s war.” New England had managed to trade with the enemy throughout the conflict, and some areas actually prospered from this commerce. Nevertheless, the Federalists claimed that the war was ruining the economy. With a possibility of secession from the Union in the background, the convention proposed a series of constitutional amendments that would protect New England interests. Instead, the end of the war, punctuated by the smashing victory at New Orleans, stamped the Federalists with a stigma of disloyalty from which they never recovered. After the Battle of New Orleans—even though the war had proven a stalemate—patriotism was running high and it was the Federalists who now came off looking like traitors. The Federalist Party melted away leaving only the Democratic Republicans still standing. No serious opposition would arise until the election of 1824.

BUILDING UNITY

The War of 1812 was, in a sense, a second war of independence that confirmed once and for all the American break with England. With its conclusion, many of the serious difficulties that the young republic had faced since the Revolution disappeared. National union under the Constitution brought a balance between liberty and order. With a low national debt and a continent awaiting exploration, the prospect of peace, prosperity, and social progress opened before the nation.

Commerce cemented national unity. The privations of war convinced many of the importance of protecting the manufacturers of America until they could stand alone against foreign competition. Economic independence, many argued, was as essential as political independence. To foster self-sufficiency, congressional leaders Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina urged a policy of protectionism — imposition of restrictions on imported goods to foster the development of American industry.

The time was favorable for raising the customs tariff. The shepherds of Vermont and Ohio wanted protection against an influx of English wool. In Kentucky, a new industry of weaving local hemp into cotton bagging was threatened by the Scottish bagging industry. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, already a flourishing center of iron smelting, was eager to challenge British and Swedish iron suppliers. The tariff enacted in 1816 imposed duties high enough to give manufacturers real protection by making American goods economically competitive with imported goods.

In addition, Westerners advocated a national system of roads and canals to link them with Eastern cities and ports, and to open frontier lands for settlement. However, they were unsuccessful in pressing their demands for a federal role in internal improvement because of opposition from New England and the South. Roads and canals remained the province of the states until the passage of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916.

Video (00:04:10) Eerie Canal (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Hi3b7KDt&sa=D&ust=1464788700329000&usg=AFQjCNFSxvG8Li4D9iOoREmmljpXY6dHFA)

The Supreme Court gets Empowered

The position of the federal government at this time was greatly strengthened by several Supreme Court decisions. A committed Federalist, John Marshall of Virginia became chief justice in 1801 and held office until his death in 1835. The court — weak before his administration — was transformed into a powerful tribunal, occupying a position co-equal to the Congress and the president. In a succession of historic decisions,

Marshall established the power of the Supreme Court and strengthened the national government. Marshall was the first in a long line of Supreme Court justices whose decisions have molded the meaning and application of the Constitution. When he finished his long service, the court had decided nearly 50 cases clearly involving constitutional issues.

Marbury vs Madison

Having lost the election of 1800, John Adams was determined to minimize the damage by packing the federal courts with as many Federalists as possible. As it was impossible for the outgoing Secretary of State to deliver all of the appointments, it fell to the new Secretary of State (James Madison) to do so. Madison refused. One of the appointees (William Marbury) petitioned the Supreme Court to force the appointments. In a brilliant decision, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that Madison should have delivered the appointment but that the Supreme Court could only act as an appellate court in this case, as it would be unconstitutional to act as a court of first resort under the particular circumstances.

The Supreme Court had not been tested in any practical way since its creation in the Constitution a dozen years prior. If the court ordered the Jefferson administration to deliver the appointments and the administration said "no," then the Supreme Court would be left with egg on their faces and clearly rendered powerless by the executive branch. By declaring Marbury legally in the right, but denying his claim because it conflicted with Article III, section II of the Constitution, Marshall had effectively and accurately "interpreted" the Constitution and nobody could do anything about it. To go against the decision, Jefferson would have to order the appointments delivered. Doing nothing would be tantamount to going along with the decision, thereby admitting the Supreme Court's right to interpret the Constitution. Jefferson did nothing.

McCulloch v. Maryland

In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), Marshall boldly upheld the Hamiltonian theory that the Constitution by implication gives the government powers beyond those expressly stated. Citing the Necessary and Proper clause of the Constitution, Marshall reasoned that Maryland’s attempt to tax all banks within the state which had not been chartered within the state was a direct attack on the Bank of the United States (the only bank in Maryland that had not been chartered in Maryland). He further reasoned that the power to tax is the power to destroy and that if Maryland retained the right to tax an institution established by the Federal Government, then Maryland could effectively claim sovereignty over the Federal Government and render it powerless. Sovereignty, Marshall reasoned, lay in the People, not in the states. Since the People had established the Constitution of the Federal Government, the People--not the States-- would retain such powers unto themselves via the Constitution.

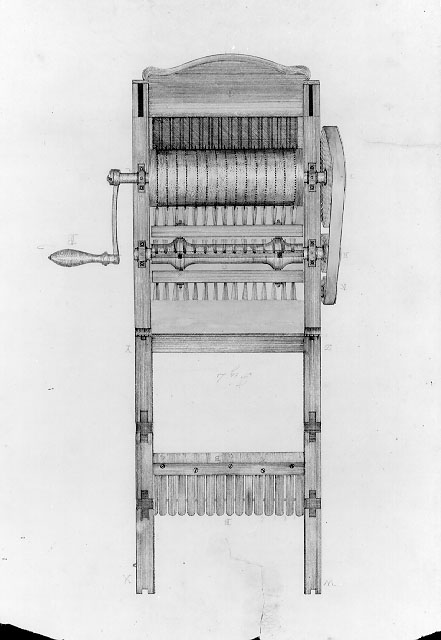

EXTENSION OF SLAVERY

null

Slavery, which up to now had received little public attention, began to assume much greater importance as a national issue. In the early years of the republic, when the Northern states were providing for immediate or gradual emancipation of the slaves, many leaders had supposed that slavery would die out. In 1786 George Washington wrote that he devoutly wished some plan might be adopted “by which slavery may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees.” Virginians Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe and other leading Southern statesmen made similar statements.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had banned slavery in the Northwest Territory. As late as 1808, when the international slave trade was abolished, there were many Southerners who thought that slavery would soon end. The expectation proved false, for during the next generation, the South became solidly united behind the institution of slavery as new economic factors made slavery far more profitable than it had been before 1790.

Chief among these was the rise of a great cotton-growing industry in the South, stimulated by the introduction of new types of cotton and by Eli Whitney’s invention in 1793 of the cotton gin, which separated the seeds from cotton. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution, which made textile manufacturing a large-scale operation, vastly increased the demand for raw cotton. And the opening of new lands in the West after 1812 greatly extended the area available for cotton cultivation. Cotton culture moved rapidly from the Tidewater states on the East Coast through much of the lower South to the delta region of the Mississippi and eventually to Texas.

Sugar cane, another labor-intensive crop, also contributed to slavery’s extension in the South. The rich, hot lands of southeastern Louisiana proved ideal for growing sugar cane profitably. By 1830 the state was supplying the nation with about half its sugar supply. Finally, tobacco growers moved westward, taking slavery with them.

As the free society of the North and the slave society of the South spread westward, it seemed politically expedient to maintain a rough equality among the new states carved out of western territories. In 1818, when Illinois was admitted to the Union, 10 states permitted slavery and 11 states prohibited it; but balance was restored after Alabama was admitted as a slave state. Population was growing faster in the North, which permitted Northern states to have a clear majority in the House of Representatives. However, equality between the North and the South was maintained in the Senate.

This Map has the following information:

Free states as of 1850 were Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Massachusetts)

Slave states as of 1850 were Texas (not including Texas claims surrendered in Compromise of 1850 and Border slave states that did not later secede in 1861), Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware.

Territories with eventual state Boundaries superimposed were New Mexico, Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and including later Gadsden Purchase of 1853

Missouri Compromise Line ran through mid California across to the east ending at the border of Arkansas and Tennessee.

Júlio Reis. Missouri Compromise Line. GNU Free Documentation License via Wikimedia Commons. United States map with Missouri Compromise Line.

Video: (00:02:11) The Presidents: Monroe Part 1(https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/play/4DZCHK) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

In 1819 Missouri, which had 10,000 slaves, applied to enter the Union. Northerners rallied to oppose Missouri’s entry except as a free state, and a storm of protest swept the country. For a time Congress was deadlocked, but Henry Clay arranged the so-called Missouri Compromise: Missouri was admitted as a slave state at the same time Maine came in as a free state. In addition, Congress banned slavery from the territory acquired by the Louisiana Purchase north of Missouri’s southern boundary. Thus, in the same way that the Northwest Ordinance set the tone of a free North, the Missouri Compromise further cemented the notion. At the time however, this provision appeared to be a victory for the Southern states because it was thought unlikely that this “Great American Desert” would ever be settled. The controversy was temporarily resolved, but Thomas Jefferson wrote to a friend that “this momentous question, like a firebell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the (death) knell of the Union.”

Video (00:02:12) The Presidents: Monroe Part 2 (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=MTW864) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

LATIN AMERICA AND THE MONROE DOCTRINE

During the opening decades of the 19th century, Central and South America turned to revolution. The idea of liberty had stirred the people of Latin America from the time the English colonies gained their freedom. Napoleon’s conquest of Spain and Portugal in 1808 provided the signal for Latin Americans to rise in revolt. By 1822, ably led by Simón Bolívar, Francisco Miranda, José de San Martín and Miguel de Hidalgo, most of Hispanic America — from Argentina and Chile in the south to Mexico in the north — had won independence.

The people of the United States took a deep interest in what seemed a repetition of their own experience in breaking away from European rule. The Latin American independence movements confirmed their own belief in self-government. In 1822 President James Monroe, under powerful public pressure, received authority to recognize the new countries of Latin America and soon exchanged ministers with them. He thereby confirmed their status as genuinely independent countries, entirely separated from their former European connections.

At just this point, Russia, Prussia, and Austria formed an association, the Holy Alliance, to protect themselves against revolution. By intervening in countries where popular movements threatened monarchies, the alliance — joined by post-Napoleonic France — hoped to prevent the spread of revolution. This policy was the antithesis of the American principle of self-determination.

As long as the Holy Alliance confined its activities to the Old World, it aroused no anxiety in the United States. But when the alliance announced its intention of restoring to Spain its former colonies, Americans became very concerned. Britain, to which Latin American trade had become of great importance, resolved to block any such action. London urged joint Anglo-American guarantees to Latin America, but Secretary of State John Quincy Adams convinced Monroe to act unilaterally: “It would be more candid, as well as more dignified, to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war.”

But how could the Americans, with their twenty ship navy, back up any unilateral action? In December 1823, with the knowledge that the British navy would defend Latin America from the Holy Alliance and France, President Monroe took the occasion of his annual message to Congress to pronounce what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine — the refusal to tolerate any further extension of European domination in the Americas:

The American continents ... are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers. We should consider any attempt on their part to extend their [political] system to any portion of this hemisphere, as dangerous to our peace and safety.

With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered, and shall not interfere. But with the governments who have declared their independence, and maintained it, and whose independence we have … acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling, in any other manner, their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition towards the United States.

The Monroe Doctrine expressed a spirit of solidarity with the newly independent republics of Latin America. These nations in turn recognized their political affinity with the United States by basing their new constitutions, in many instances, on the North American model. The result was a diplomatic coup for the United States and a foreign policy posture that would stand unopposed until the 1980s.

FACTIONALISM AND POLITICAL PARTIES

Domestically, the presidency of Monroe (1817-1825) was termed the “era of good feelings.” The phrase acknowledged the political triumph of the Republican Party over the Federalist Party, which had collapsed as a national force. All the same, this was a period of vigorous factional and regional conflict.

Video: (00:02:57) The Presidents: John Quincy Adams (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=33HNQG) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

The end of the Federalists led to a brief period of factional politics and brought disarray to the practice of choosing presidential nominees by congressional party caucuses. For a time, state legislatures nominated candidates. In 1824 Tennessee and Pennsylvania chose Andrew Jackson, with South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun as his running mate. Kentucky selected Speaker of the House Henry Clay; Massachusetts, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, son of the second president, John Adams. A congressional caucus, widely derided as undemocratic, picked Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford.

Personality and sectional allegiance played important roles in determining the outcome of the election. Adams won the electoral votes from New England and most of New York; Clay won Kentucky, Ohio, and Missouri; Jackson won the Southeast, Illinois, Indiana, the Carolinas, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and New Jersey; and Crawford won Virginia, Georgia, and Delaware. No candidate gained a majority in the Electoral College, so, according to the provisions of the Constitution, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives, where Clay was the most influential figure. He supported Adams, who gained the presidency.

This political cartoon appeared in the Niles Weekly Register regarding the "Corrupt Bargain" accusations made against Secretary of State Henry Clay. Secretary Clay is shown restraining a seated, uniformed General Jackson and sewing up his mouth. From Clay's pocket protrudes a slip of paper reading, "cure for calumny." Below the image is a quote from Shakespeare's "Hamlet," ". . . Clay might stop a hole, to keep the wind away." On the wall behind him are the words "Plain sewing done here."

Video: (00:01:50)The Presidents: John Quincy Adams (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=Y2KRQA) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

During Adams’s administration, new party alignments appeared. Adams’s followers, some of whom were former Federalists, took the name of “National Republicans” as emblematic of their support of a federal government that would take a strong role in developing an expanding nation. Though he governed honestly and efficiently, Adams was not a popular president. He failed in his effort to institute a national system of roads and canals. His coldly intellectual temperament did not win friends. Jackson, by contrast, had enormous popular appeal and a strong political organization. His followers coalesced to establish the Democratic Party, claimed direct lineage from the Democratic- Republican Party of Jefferson, and in general advocated the principles of small, decentralized government. Mounting a strong anti-Adams campaign, they accused the president of a “corrupt bargain” for naming Clay secretary of state. In the election of 1828, Jackson defeated Adams by an overwhelming electoral majority.

![General Jackson. [Public Domain] Library of Congress](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7592)

Portrait of General Jackson

Video: (00:02:54) The Presidents: Jackson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=V2RT9L) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

Jackson — Tennessee politician, Indian fighter on the Southern frontier, and hero of the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812 — drew his support from the “common people.” He came to the presidency on a rising tide of enthusiasm for popular democracy. The election of 1828 was a significant benchmark in the trend toward broader voter participation. By then most states had either enacted universal white male suffrage or minimized property requirements. In 1824 members of the Electoral College in six states were still selected by the state legislatures. By 1828 presidential electors were chosen by popular vote in every state but Delaware and South Carolina. These developments were the products of a widespread sense that the people should rule and that government by traditional elites had come to an end.

Video (00:07:43) The Hermitage (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/g9KPc3w7&sa=D&ust=1464788700369000&usg=AFQjCNEQrLiwfi5MHfYEjSneGWB4Sno4aA)

NULLIFICATION CRISIS

Video (00:01:52) The Presidents: Jackson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&AssignmentID=GPFLM5) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

Toward the end of his first term in office, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South Carolina, the most important of the emerging Deep South cotton states, on the issue of the protective tariff. Business and farming interests in the state had hoped that the president would use his power to modify the 1828 act that they called the Tariff of Abominations. In their view, all its benefits of protection went to Northern manufacturers, leaving agricultural South Carolina poorer.

![John C. Calhoun. [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7593)

portrait of John C. Calhoun

In 1828, the state’s leading politician — and Jackson’s vice president until his resignation in 1832 — John C. Calhoun had declared in his South Carolina Exposition and Protest that states had the right to nullify oppressive national legislation. In 1832, Congress passed and Jackson signed a bill that revised the 1828 tariff downward, but it was not enough to satisfy most South Carolinians. The state adopted an Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void within state borders. Its legislature also passed laws to enforce the ordinance, including authorization for raising a military force and appropriations for arms. Nullification was a long-established theme of protest against perceived excesses by the federal government. Jefferson and Madison (the primary authors of the Declaration and the Constitution respectively) had proposed it in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798, to protest the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Hartford Convention of 1814 had invoked it to protest the War of 1812. Never before, however, had a state actually attempted nullification. The young nation faced its most dangerous crisis yet.

In response to South Carolina’s threat, Jackson sent seven small naval vessels and a man-of-war to Charleston in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a resounding proclamation against the nullifiers. South Carolina, the president declared, stood on “the brink of insurrection and treason,” and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to the Union. He also let it be known that, if necessary, he personally would lead the U.S. Army to enforce the law.

When the question of tariff duties again came before Congress, Jackson’s political rival, Senator Henry Clay, a great advocate of protection but also a devoted Unionist, sponsored a compromise measure. Clay’s tariff bill, quickly passed in 1833, specified that all duties in excess of 20 percent of the value of the goods imported were to be reduced year by year, so that by 1842 the duties on all articles would reach the level of the moderate tariff of 1816. At the same time, Congress passed a Force Act, authorizing the president to use military power to enforce the laws.

South Carolina had expected the support of other Southern states, but instead found itself isolated. Its most likely ally, the state government of Georgia, had recently sought, and received, U.S. military force to remove Native American tribes from the state. Eventually, South Carolina rescinded its action. Both sides, nevertheless, claimed victory. Jackson had strongly defended the Union. But South Carolina, by its show of resistance, had obtained many of its demands and had demonstrated that a single state could force its will on Congress. As a parting shot, South Carolina retained the doctrine of nullification by nullifying Congress’s “Force Bill.”

THE BANK FIGHT

![This political cartoon depicts Jackson battling a many-headed monster that represents the bank. [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7594)

A political cartoon of Jackson battling a snake with 21 human heads which represents the Bank.

Video (00:06:02) The Presidents: Jackson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=ZLHPBA) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

Although the nullification crisis possessed the seeds of civil war, it was not as critical a political issue as a bitter struggle over the continued existence of the nation’s central bank, the second Bank of the United States. The first bank, established in 1791 under Alexander Hamilton’s guidance, had been chartered for a 20-year period. Though the government held some of its stock, the bank, like the Bank of England and other central banks of the time, was a private corporation with profits passing to its stockholders. Its public functions were to act as a depository for government receipts, to make short-term loans to the government, and above all to establish a sound currency by refusing to accept at face value notes (paper money) issued by state-chartered banks in excess of their ability to redeem.

To the Northeastern financial and commercial establishment, the central bank was a needed enforcer of prudent monetary policy, but from the beginning it was resented by Southerners and Westerners who believed their prosperity and regional development depended upon ample money and credit. The Republican Party of Jefferson and Madison doubted its constitutionality. When its charter expired in 1811, it was not renewed.

For the next few years, the banking business was in the hands of state-chartered banks, which issued currency in excessive amounts, creating great confusion and fueling inflation. It became increasingly clear that state banks could not provide the country with a reliable currency. In 1816 a second Bank of the United States, similar to the first, was again chartered for 20 years. From its inception, the second bank was unpopular in the newer states and territories, especially with state and local bankers who resented its virtual monopoly over the country’s credit and currency, but also with less prosperous people everywhere, who believed that it represented the interests of the wealthy few.

On the whole, the bank was well managed and rendered a valuable service; but Jackson had long shared the Republican distrust of the financial establishment. Nicholas Biddle, the bank’s president, reasoned that by applying for an early re-chartering of the bank (necessary every 20 years) that he could force Jackson to alienate half the population during the presidential election year, whether he signed or vetoed the bill, thereby losing the election. Jackson recognized Biddle’s blatant political manipulation and resolved, not only to veto the bill, but to pull all federal funds out of the bank before its charter expired. This, he did, thereby destroying the bank and sending the national economy into chaos as state banks grew wildly speculative without the oversight of the Bank of the United States.

In the presidential campaign that followed, the bank question revealed a fundamental division. Established merchant, manufacturing, and financial interests favored sound money. Regional bankers and entrepreneurs on the make wanted an increased money supply and lower interest rates. Other debtor classes, especially farmers, shared those sentiments. Jackson and his supporters called the central bank a “monster” and coasted to an easy election victory over Henry Clay.

The president interpreted his triumph as a popular mandate to crush the central bank irrevocably. In September 1833 he ordered an end to deposits of government money in the bank, and gradual withdrawals of the money already in its custody. The government deposited its funds in selected state banks, characterized as “pet banks” by the opposition.

For the next generation the United States would get by on a relatively unregulated state banking system, which helped fuel westward expansion through cheap credit but kept the nation vulnerable to periodic panics. During the Civil War, the United States initiated a system of national charters for local and regional banks, but the nation returned to a central bank only with the establishment of the Federal Reserve system in 1913.

WHIGS, DEMOCRATS, AND KNOW-NOTHINGS

Jackson’s political opponents, united by little more than a common opposition to him, eventually coalesced into a common party called the Whigs, a British term signifying opposition to Jackson’s “monarchical rule.” Although they organized soon after the election campaign of 1832, it was more than a decade before they reconciled their differences and were able to draw up a platform. Largely through the magnetism of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, the Whigs’ most brilliant statesmen, the party solidified its membership. But in the 1836 election, the Whigs were still too divided to unite behind a single man. New York’s Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s vice president, won the contest.

Video: (00:01:58) The Presidents: Van Buren (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=65KMZP) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

An economic depression and the larger-than-life personality of his predecessor obscured Van Buren’s merits. His public acts aroused no enthusiasm, for he lacked the compelling qualities of leadership and the dramatic flair that had attended Jackson’s every move. The election of 1840 found the country afflicted with hard times and low wages — and the Democrats on the defensive.

The Whig candidate for president was William Henry Harrison of Ohio, vastly popular as a hero of conflicts with Native Americans and the War of 1812. He was promoted, like Jackson, as a representative of the democratic West. His vice presidential candidate was John Tyler — a Virginian whose views on states’ rights and a low tariff were popular in the South. Harrison won a sweeping victory.

Video (00:01:48) The Presidents: Harrison (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=A4W8GV) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

Within a month of his inauguration, however, the 68-year-old Harrison died, and Tyler became president. Tyler’s beliefs differed sharply from those of Clay and Webster, still the most influential men in Congress. The result was an open break between the new president and the party that had elected him. The Tyler presidency would accomplish little other than to establish definitively that, if a president died, the vice president would assume the office with full powers for the balance of his term.

Video: (00:04:19) The Presidents: Tyler (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=WFYCXC) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

Americans found themselves divided in other, more complex ways. The large number of Catholic immigrants in the first half of the 19th century, primarily Irish and German, triggered a backlash among native-born Protestant Americans. Immigrants brought strange new customs and religious practices to American shores. They competed with the native-born for jobs in cities along the Eastern seaboard. The coming of universal white male suffrage in the 1820s and 1830s increased their political clout. Displaced patrician politicians blamed the immigrants for their fall from power. The Catholic Church’s failure to support the temperance movement gave rise to charges that Rome was trying to subvert the United States through alcohol.

The most important of the nativist organizations that sprang up in this period was a secret society, the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, founded in 1849. When its members refused to identify themselves, they were swiftly labeled the “Know- Nothings.” In a few years, they became a national organization with considerable political power.

The Know-Nothings advocated an extension in the period required for naturalized citizenship from five to 21 years. They sought to exclude the foreign-born and Catholics from public office. In 1855 they won control of legislatures in New York and Massachusetts; by then, about 90 U.S. congressmen were linked to the party. That was its high point. Soon after, the gathering crisis between North and South over the extension of slavery fatally divided the party, consuming it along with the old debates between Whigs and Democrats that had dominated American politics in the second quarter of the 19th century.

STIRRINGS OF REFORM

The democratic upheaval in politics exemplified by Jackson’s election was merely one phase of the long American quest for greater rights and opportunities for all citizens. Another was the beginning of labor organization, primarily among skilled and semiskilled workers. In 1835 labor forces in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, succeeded in reducing the old “dark-to-dark” workday to a 10-hour day. By 1860, the new work day had become law in several of the states and was a generally accepted standard.

!["Woman's Holy War. Grand Charge on the Enemy's Works." [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7595)

An allegorical 1874 political cartoon print, which somewhat unusually shows temperance campaigners (alcohol prohibition advocates) as virtuous armored women warriors (riding sidesaddle), wielding axes Carrie-Nation-style to destroy barrels of Beer, Whisky, Gin, Rum, Brandy, Wine and Liquors, under the banners of "In the name of God and humanity" and "Temperance League". The foremost woman bears the shield seen in the Seal of the United States (based on the U.S. flag), suggesting the patriotic motivations of temperance campaigners.

The spread of suffrage had already led to a new concept of education. Clear-sighted statesmen everywhere understood that universal suffrage required a tutored, literate electorate. Workingmen’s organizations demanded free, tax supported schools open to all children. Gradually, in one state after another, legislation was enacted to provide for such free instruction. The leadership of Horace Mann in Massachusetts was especially effective. The public school system became common throughout the North. In other parts of the country, however, the battle for public education continued for years.

Another influential social movement that emerged during this period was the opposition to the sale and use of alcohol, or the temperance movement. It stemmed from a variety of concerns and motives: religious beliefs, the effect of alcohol on the work force, the violence and suffering women and children experienced at the hands of heavy drinkers. In 1826 Boston ministers organized the Society for the Promotion of Temperance. Seven years later, in Philadelphia, the society convened a national convention, which formed the American Temperance Union. The union called for the prohibition of all alcoholic beverages, and pressed state legislatures to ban their production and sale. Thirteen states had done so by 1855, although the laws were subsequently challenged in court. They survived only in northern New England, but between 1830 and 1860 the temperance movement reduced Americans’ per capita consumption of alcohol.

Other reformers addressed the problems of prisons and care for the insane. Efforts were made to turn prisons, which stressed punishment, into penitentiaries where the guilty would undergo rehabilitation. In Massachusetts, Dorothea Dix led a struggle to improve conditions for insane persons, who were kept confined in wretched almshouses and prisons. After winning improvements in Massachusetts, she took her campaign to the South, where nine states established hospitals for the insane between 1845 and 1852.

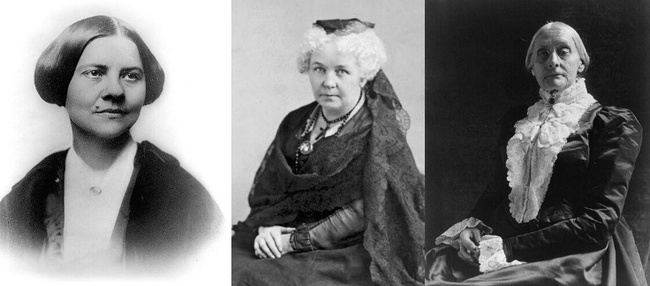

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Such social reforms brought many women to a realization of their own unequal position in society. From colonial times, unmarried women had enjoyed many of the same legal rights as men, although custom required that they marry early. With matrimony, women virtually lost their separate identities in the eyes of the law. Women were not permitted to vote. Their education in the 17th and 18th centuries was limited largely to reading, writing, music, dancing, and needlework.

The awakening of women began with the visit to America of Frances Wright, a Scottish lecturer and journalist, who publicly promoted women’s rights throughout the United States during the 1820s. At a time when women were often forbidden to speak in public places, Wright not only spoke out, but shocked audiences by her views advocating the rights of women to seek information on birth control and divorce. By the 1840s an American women’s rights movement emerged. Its foremost leader was Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In 1848 Stanton and her colleague Lucretia Mott organized a women’s rights convention — the first in the history of the world — at Seneca Falls, New York. Delegates drew up a “Declaration of Sentiments,” demanding equality with men before the law, the right to vote, and equal opportunities in education and employment. The resolutions passed unanimously with the exception of the one for women’s suffrage, which won a majority only after an impassioned speech in favor by Frederick Douglass, the black abolitionist.

At Seneca Falls, Elizabeth Cady Stanton gained national prominence as an eloquent writer and speaker for women’s rights. She had realized early on that without the right to vote, women would never be equal with men. Taking the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison as her model, she saw that the key to success lay in changing public opinion, and not in party action. Seneca Falls became the catalyst for future change. Soon other women’s rights conventions were held, and other women would come to the forefront of the movement for their political and social equality.

Video: (00:05:04) Women’s Suffrage (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Gy3f2WRm&sa=D&ust=1464788700398000&usg=AFQjCNFU_GXb2SjDKGc5nS2qpAl2zFSpYA)

In 1848 also, Ernestine Rose, a Polish immigrant, was instrumental in getting a law passed in the state of New York that allowed married women to keep their property in their own name. Among the first laws in the nation of this kind, the Married Women’s Property Act encouraged other state legislatures to enact similar laws.

In 1869 Stanton and another leading women’s rights activist, Susan B. Anthony, founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) to promote a constitutional amendment for women’s right to the vote. These two would become the women’s movement’s most outspoken advocates. Describing their partnership, Stanton would say, “I forged the thunderbolts and she fired them.”

WESTWARD

![“Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way” by Emanuel Leutze [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7596)

A stream of rugged pioneers is shown travelling with horses, oxen, and covered wagons across a mountainous landscape.

The frontier did much to shape American life. Conditions along the entire Atlantic seaboard stimulated migration to the newer regions. From New England, where the soil was incapable of producing high yields of grain, came a steady stream of men and women who left their coastal farms and villages to take advantage of the rich interior land of the continent. In the backcountry settlements of the Carolinas and Virginia, people handicapped by the lack of roads and canals giving access to coastal markets and resentful of the political dominance of the Tidewater planters also moved westward. By 1800 the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys were becoming a great frontier region. “Hi-o, away we go, floating down the river on the Ohi- o,” became the song of thousands of migrants.

The westward flow of population in the early 19th century led to the division of old territories and the drawing of new boundaries. As new states were admitted, the political map stabilized east of the Mississippi River. From 1816 to 1821, six states were created — Indiana, Illinois, and Maine (which were free states), and Mississippi, Alabama, and Missouri (slave states).The first frontier had been tied closely to Europe, the second to the coastal settlements, but the Mississippi Valley was independent and its people looked west rather than east.

![By User:Golbez. derivative work: Kenmayer (United_States_1821-07-1821-08.png) [CC BY 2.5, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7597)

Map showing established states and territories in the United States in 1821. Slave states are indicated as Missouri, Kentucky, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. Slave territories are indicated as Arkansas Territory and Florida Territory. Established free states are Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Vermont, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine.

Frontier settlers were a varied group. One English traveler described them as “a daring, hardy race of men, who live in miserable cabins. ... They are unpolished but hospitable, kind to strangers, honest, and trustworthy. They raise a little Indian corn, pumpkins, hogs, and sometimes have a cow or two. ... But the rifle is their principal means of support.” Dexterous with the axe, snare, and fishing line, these men blazed the trails, built the first log cabins, and confronted Native American tribes, whose land they occupied.

As more and more settlers penetrated the wilderness, many became farmers as well as hunters. A comfortable log house with glass windows, a chimney, and partitioned rooms replaced the cabin; the well replaced the spring. Industrious settlers would rapidly clear their land of timber, burning the wood for potash and letting the stumps decay. They grew their own grain, vegetables, and fruit; ranged the woods for deer, wild turkeys, and honey; fished the nearby streams; looked after cattle and hogs. Land speculators bought large tracts of the cheap land and, if land values rose, sold their holdings and moved still farther west, making way for others.

Doctors, lawyers, storekeepers, editors, preachers, mechanics, and politicians soon followed the farmers. The farmers were the sturdy base, however. Where they settled, they intended to stay and hoped their children would remain after them. They built large barns and brick or frame houses. They brought improved livestock, plowed the land skillfully, and sowed productive seed. Some erected flour mills, sawmills, and distilleries. They laid out good highways, and built churches and schools. Incredible transformations were accomplished in a few years. In 1830, for example, Chicago, Illinois, was merely an unpromising trading village with a fort; but long before some of its original settlers had died, it had become one of the largest and richest cities in the nation.

![“Imagined view of Wolf Point, Chicago, Illinois, USA as it might have appeared in 1830” By Alfred Theodore Andreas (1839–1900) (History of Chicago [1]) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7598)

In this imagined view of Chicago, circa 1830, two buildings with log construction are situated near the fork of a river. A small rowboat is pulled up on shore. Tall weeds are growing on the banks of the river. One or two more buildings are visible in the distance.

![Chicago, shortly before 1871 By unknown artist (The American Cyclopædia, v. 4, 1879, p. 398.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7599)

In this illustration of Chicago around 1871, a busy waterway is shown with dozens of boats of various sizes. Beyond the shore, buildings and street gridlines stretch to the horizon.

Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny put quite simply, was a conviction that God had granted the continent of North America to white Americans—that dominating the land from “sea to shining sea” was a God-ordained right and duty. The White Man’s Burden, which naturally flowed from this species of thinking, was to subdue, civilize and educate natives in the American West and eventually any others who did not subscribe to Democracy, Christianity and Progress.

![“American Progress” By John Gast (painter) (scan or photograph of 1872 painting) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7600)

A scene of westward expansion is dominated by a woman dressed in Roman-style, flowing white robes, who float across the sky. She is holding a book in her right hand, and stringing along telegraph wire with her left. To the east, the sky is bright; to the west, it is dark and cloudy. Native Americans and bison are depicted fleeing into the stormy West, while settlers, wagons and trains move westward across the canvas.

Farms in the West were easy to acquire. Government land after 1820 could be bought for $1.25 for just over an acre, and after the 1862 Homestead Act, could be claimed by merely occupying and improving it. In addition, tools for working the land were easily available. It was a time when, in a phrase coined by Indiana newspaperman John Soule and popularized by New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, young men could “go west and grow with the country.”

Except for a migration into Mexican- owned Texas, the westward march of the agricultural frontier did not pass Missouri into the vast Western territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase until after 1840. In 1819, in return for assuming the claims of American citizens to the amount of $5 million, the United States obtained from Spain both Florida and Spain’s rights to the Oregon country in the Far West. In the meantime, the Far West had become a field of great activity in the fur trade, which was to have significance far beyond the value of the skins. As in the first days of French exploration in the Mississippi Valley, the trader was a pathfinder for the settlers beyond the Mississippi. The French and Scots-Irish trappers, exploring the great rivers and their tributaries and discovering the passes through the Rocky and Sierra Mountains, made possible the overland migration of the 1840s and the later occupation of the interior of the nation.

Video: (00:02:26) Mountain Men (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewPlaylist.aspx?AssignmentID=P8VJJT) This video is accessible to NMC students only (login required).

Overall, the growth of the nation was enormous: The population grew from 7.25 million to more than 23 million from 1812 to 1852, and the land available for settlement increased by almost the size of Western Europe — from 2.7 million to 4.8 million square miles. Still unresolved, however, were the basic conflicts rooted in sectional differences that, by the decade of the 1860s, would explode into civil war. Inevitably, too, this westward expansion brought settlers into conflict with the original inhabitants of the land: the Native Americans.

Indian Removal

A two-story building stands in the middle of the photo. Several smaller buildings are partially visible behind some trees.

![Cherokee Syllabary. By Sakurambo at English Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7602)

A picture of the Cherokee Syllabary looks very different than an English alphabet including many swirls not found in english characters.

![Title page, [Constitution and laws of the Cherokee nation] 1875. [Public domain], via Library of Congress.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7603)

The title page is written in Cherokee script, and shows the seal of the Cherokee nation, which is a seven-pointed star encircled by a wreath of oak leaves.

During the Jefferson presidency a policy of assimilation had been pursued with regard to the Indian population. Indians were to be “civilized,” and brought into the dominant culture. No tribe had succeeded in assimilation as had the Cherokee of Georgia. Family farms, constitutional law, even Christianity had become commonplace throughout Cherokee lands—lands which had been guaranteed by federal treaty in 1791. Then gold was discovered on Cherokee land. A flood of white squatter-miners led the state of Georgia to legislate the Cherokee right out of their lands. A Cherokee appeal to the Supreme Court ended in the 1831 ruling that the Cherokee had a right to remain. All that remained was for the Chief Executive (Andrew Jackson) to enforce the ruling. In perhaps the most flagrant violation in the history of the Constitution, Andrew Jackson replied that “Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” Four thousand Cherokee died on the forced march to Oklahoma.

![By User: Nikater [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7604)

Map of the route of the Trails of Tears — for ethnic cleansing of Native Americans from the Southeastern United States between 1836 and 1839.The forced march of Cherokee removal from the Southeastern United States for forced relocation to the Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma)

THE FRONTIER, “THE WEST,” AND THE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE

The frontier — the point at which settled territory met “unoccupied land” — began at Jamestown and Plymouth Rock. It moved in a westward direction for nearly 300 years through densely forested wilderness and barren plains until the decennial census of 1890 revealed that at last the United States no longer possessed a discernible line of settlement.

At the time it seemed to many that a long period had come to an end — one in which the country had grown from a few struggling outposts of English civilization to a huge independent nation with an identity of its own. It was easy to believe that the experience of settlement and post-settlement development, constantly repeated as a people conquered a continent, had been the defining factor in the nation’s development.

In 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, expressing a widely held sentiment, declared that the frontier had made the United States more than an extension of Europe. It had created a nation with a culture that was perhaps coarser than Europe’s, but also more pragmatic, energetic, individualistic, and democratic. The existence of large areas of “free land” had created a nation of property holders and had provided a “safety valve” for discontent in cities and more settled areas. His analysis implied that an America without a frontier would trend ominously toward what were seen as the European ills of stratified social systems, class conflict, and diminished opportunity.

After more than a hundred years scholars still debate the significance of the frontier in American history. Few believe it was quite as all-important as Turner suggested; its absence does not appear to have led to dire consequences. Some have gone farther, rejecting the Turner argument as a romantic glorification of a bloody, brutal process — marked by a war of conquest against Mexico, near-genocidal treatment of Native American tribes, and environmental despoliation. The common experience of the frontier, they argue, was one of hardship and failure.

Yet it remains hard to believe that three centuries of westward movement had no impact on the national character and suggestive that intelligent foreign observers, such as the French intellectual Alexis de Tocqueville, were fascinated by the American West. Indeed, the last area of frontier settlement, the vast area stretching north from Texas to the Canadian border, which Americans today commonly call “the West,” still seems characterized by ideals of individualism, democracy, and opportunity that are more palpable than in the rest of the nation. It is perhaps also revealing that many people in other lands, when hearing the word “American,” so often identify it with a symbol of that final frontier — the “cowboy.”