Chapter 3 Colonies

Total Video: 0:37.96

Introduction

England was the late-comer to the colonization game. While France and England both envied the Spanish ability to drain wealth from the New World, neither, ultimately, would be able to duplicate it. As the French began developing their fur empire, the English made halting, fitful attempts on the eastern coast of North America in two very different colonization efforts. One involved the same sort of adventurers the French and Spanish had employed—only, these spoke English. The other involved religious refugees who were stamped of a completely different mold altogether.

These two English Settlements in Virginia and Massachusetts would develop along very different lines from each other. The Virginia settlements, beginning with Jamestown, would know suffering, violence and want for over a decade after their initial establishment. In Massachusetts, beginning with Plymouth, and later Boston, a difficult winter would be followed by tremendous success-- comparatively speaking-- in relations with the native locals, economic endeavors and health.

What they Found

The colonists’ first glimpse of the new land was a vista of dense woods. The settlers might not have survived had it not been for the help of friendly Indians, who taught them how to grow native plants — pumpkin, squash, beans, and corn. In addition, the vast, virgin forests, extending nearly 1,300 miles along the Eastern seaboard, proved a rich source of game and firewood. They also provided abundant raw materials used to build houses, furniture, ships, and profitable items for export.

Although the new continent was remarkably endowed by nature, trade with Europe was vital for articles the settlers could not produce. The coast served the immigrants well. The whole length of shore provided many inlets and harbors. Only two areas — North Carolina and southern New Jersey — lacked harbors for ocean-going vessels.

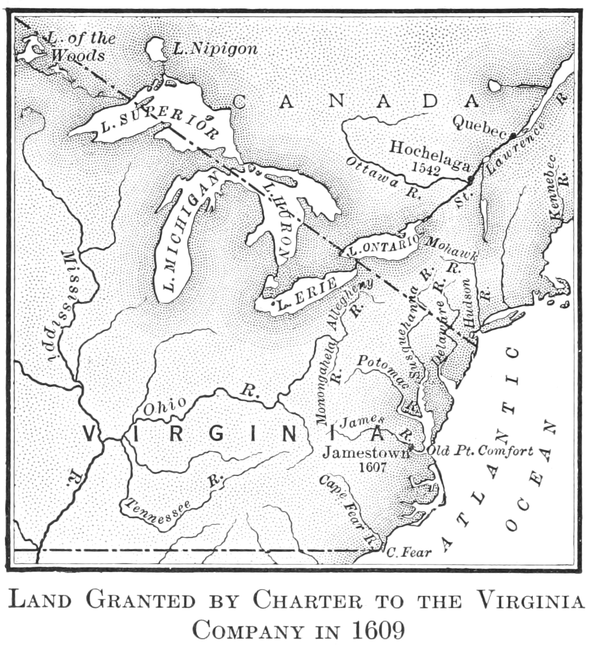

Majestic rivers — the Kennebec, Hudson, Delaware, Susquehanna, Potomac, and numerous others — linked lands between the coast and the Appalachian Mountains with the sea. Only one river, however, the St. Lawrence — dominated by the French in Canada — offered a water passage to the Great Lakes and the heart of the continent. Dense forests, the resistance of some Indian tribes, and the formidable barrier of the Appalachian Mountains discouraged settlement beyond the coastal plain. Only trappers and traders ventured into the wilderness. For the first hundred years the colonists built their settlements compactly along the coast.

The Virginia Company

Unlike Spain and France, English colonization efforts were private enterprises. As such, they were approved, but not funded, by the Crown. The Virginia Company of London was such an endeavor. As a Joint Stock Company, its operating capital came from a multitude of investors hoping to see a return in the form of precious metals, glass, dyes and other products from the colony. One way of investing was to invest oneself in the form of Indenture. An indentured servant could, for example, offer his or her services for several years in exchange for acreage and tools at the end of service.

Indentured Servitude became a real option to the poor as English lands were being enclosed for the raising of sheep to support English textile mills, thus throwing many farming peasants out of work to make room for sheep. Because the ownership of land was equated with nobility and wealth, the promise of acreage and upward mobility in the New World sounded much better than starvation or debtor's prison in the old.

Three ships, one owned, two hired, by the Virginia Company landed in April, 1607 in Virginia's Chesapeake Bay. They traveled fifty miles up the "James" River and named their settlement "Jamestown" after their king.

Jamestown

The first settlers at Jamestown had hoped to find gold (as had the Spanish) and Indians to enslave (as had the Spanish) for the purpose of extracting the gold. What they found was a malarial swamp and Indians who, if they hadn’t initially taken pity on the new settlers, could have very likely enslaved the Englishmen. After a year in Jamestown, only 38 of 144 were still alive. If not for the severe discipline imposed by Captain John Smith, even these few would not likely have survived.

Video: Jamestown 3:48(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/n6DWp25Q)

Powhatan

For his part, Powhatan—leader of the local Indian confederation bearing his name—viewed the new settlers as potential allies against his enemies. At the very least he had no desire to see the new-comers and their booming weapons allied with one of his rivals. After English raids on village corn supplies and various attempts by both sides to avoid open warfare, Powhatan withdrew all help from the struggling colonists. In this, Powhatan won the day for about a day.

Video: Powhatan Village (2:59)(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/g9NQy5t3)

The colonists, despairing of making it on their own, and lacking supplies, left Jamestown and sailed the fifty miles back to the edge of the Atlantic where they spent the night in a sheltered cove in anticipation of the Atlantic crossing. In the morning, sails were spotted on the eastern horizon. The colonists returned to Jamestown with new provisions and settled in.

Early Growth

Early Jamestown was as much a graveyard as it was a settlement. Colonists continued to be lured across the Atlantic with promises of acreage and tools in return for a set time of indentured service—usually seven years. They came and they died in a seemingly endless cycle. By 1618, there were still only 1,000 colonists in Virginia. Over the next six years another 4,000 joined them. One year later, in 1625, the population stood at 1,210. The clear disaster that was Jamestown prompted the King to dissolve the Virginia Company charter and declare all of Virginia a royal colony in 1624.

Video: More on Jamestown 8:23(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/j4QFa75D)

Economic Salvation

No gold was found in Jamestown but in 1611 John Rolfe successfully introduced tobacco into the colony and it quickly became the preferred cash crop. In fact, colonists were so eager to profit from the “stinking weed,” as King James called it, that the colonial authorities had to force each settler to grow a prescribed acreage of foodstuffs to ensure the settlement’s survival. Like the French and their furs, the Jamestown settlers put their crop on the market and eventually found Spanish gold in their pockets, which had been their goal in the first place.

Early Tremors

Prior to the colony being royalized, the Virginia Company had established the House of Burgesses in 1619. This meant essentially a local government—in Virginia. More importantly, it was an admission that the Virginia Company could not govern the colony from 3,000 miles distant in London; the settlement had immediate needs which required immediate attention. Company propagandists had long promoted the temptation of land and wealth to entice people into removing from England to Virginia. To this they added the enticement of self-government. Let it suffice to say that Virginians quickly learned to jealously guard their “right” to govern themselves so they could continue to “do as they wished.”

Powhatan’s End

Tense relations between the Powhatan tribe and the English settlers at Jamestown were briefly put at ease with the marriage of Chief Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas and John Rolfe in 1614. Following her death in 1617 and Chief Powhatan’s death the next year, Opechancanough (Chief Powhatan’s brother) led the Powhatans in a surprise attack in 1622 with the intention of either driving out the English or winning their respect as cohabitants of the land. Nearly 400 (about a third) of the colonists living in the vicinity of Jamestown were killed, while Jamestown itself had been spared due to warning from a local Indian boy. Instead of respect, the English were incensed, went to war, and destroyed so much of the Powhatan’s corn supply that Opechancanough sued for peace.

The Issue

The dispute was primarily over land. The English had settled on tobacco as the colony’s economic engine. Tobacco, as it turns out, requires a great deal of land and depletes the soil quickly—thus requiring even more land. It was not long before the English and the Powhatans were bumping against each other agriculturally. When Opechancanough decided that the English expansion would continue unchecked, the attack was planned for the morning of Good Friday in 1622. A second attempt by Opechancanough in 1644 killed about 500 colonists but ended in decisive defeat and subjected the remainder of the tribe to the English Crown.

Puritans Arrive in Massachusetts

When Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church in the 1530s, there were those who misinterpreted the break as a serious theological rift. These "Puritans" wished to "purify" the catholic elements out of the Anglican Church. Puritans came in two flavors: Congregationalists and Separatists. The Congregationalist Puritans believed the Church of England could be reformed and they stayed in England to accomplish just that. The Separatist Puritans had given up on reform and sought to break away from the Church of England and begin anew.

Pilgrims

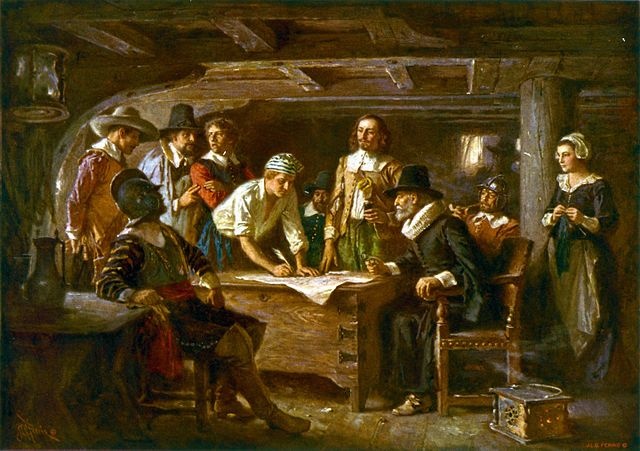

The same year Jamestown was founded, a group of Separatist Puritans left England for Leyden, Holland in an effort to live and raise their families in good conscience and out of England. King James had made it clear that all English subjects were to worship only as prescribed by the Anglican Church and its Common Book of Prayer "or else." The Separatist Puritans saw no reason to experience "or else" and sailed across the channel. After a decade in Holland the Separatist Puritans, discriminated against by the Dutch, and realizing that their children were growing up Dutch rather than English, applied to the Virginia Company of London for a land grant. Receiving this, they sailed in the Mayflower for "Northern Virginia."

Difficult weather and contrary trade winds made it clear that they would land well north of the Virginia claim in “ungoverned” territory, so an agreement of government was quickly drawn up before landfall. This "Mayflower Compact" pledged all to working for the good of the community, rather than for mere individual gain.

Video: Plymouth 8:50 (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Xm47Tig5)

Plymouth

Nearly half of the original Pilgrims (Puritan Separatists) aboard the Mayflower had taken ill and died by the time Plymouth colony was established in Cape Cod. Having missed their goal of the northern part of the Virginia claim and drawn up the Mayflower Compact for mutual governance, the settlers wintered aboard the Mayflower while a search party scouted for a suitable settlement. Once Plymouth was selected, the Ship was brought to anchorage and the settlement began to take shape in Spring of 1621.

They immediately set about planting, assisted by a local English-speaking Indian named Tisquantum, then celebrated the first Thanksgiving for the first harvest of that same year with about ninety local Indians and their chiefs. Curiously, the story of “Squanto” teaching the pilgrims to bury fish to fertilize their maize, has an interesting twist; he probably learned the trick from the Spaniards years earlier during his captivity in Europe.

The Plymouth colony was so successful, that they were able to buy out their London backers in 1627 and divide all property amongst the local families. Buying out their backers made them essentially a self-governing settlement--the second such English settlement in the New World that would learn to jealously guard its “right” to govern itself.

The Great Puritan Migration

![John Winthrop [artist unidentified], Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/1372)

Meanwhile, back in England, James I was succeeded by his Son Charles I in 1625. It happened that Charles hated Puritans even more than his father James. Accordingly, the Congregationalist Puritans began to lose hope of reforming the Anglican Church; in fact, many of them fled for their lives. Their leader, John Winthrop, urged them to create a “city upon a hill” in the New World — a place where they would live in strict accordance with their religious beliefs and set an example for all Christendom.

A group of these Puritans, led by Winthrop, began the Massachusetts Bay Company while still in England, then sailed to Massachusetts in 1629, taking the company charter with them.

This meant that this newest Puritan settlement of Boston would be a third self-governing unit and it quickly became jealously protective of its right to do so. Under the charter’s provisions, power rested with the General Court, which was made up of “free men” required to be members of the Puritan, or “Congregational”, Church. This guaranteed that the Puritans would be the dominant political as well as religious force in the colony. The General Court elected the governor, who for most of the next generation would be John Winthrop. By 1630, there were 1,000 people in the settlement and by 1640 as many as 9,000 people throughout Massachusetts, with Boston emerging as the economic center of the colony.

Differences

The English Puritans in Massachusetts were distinctly different from the English settlers at Jamestown and their Spanish and French counterparts. The Puritans had come to the New World as families intending to stay and replicate that part of English society which they approved of. This meant they would grow in population much more quickly than Jamestown, build more permanent structures, approach town building in a more organized fashion and have a greater sense of community welfare compared to the highly individualistic loners of Jamestown.

These Puritans valued liberty for the ability it gave them to "do the right” thing as they saw it--a decidedly different perspective than the Jamestown settlers who valued liberty for the ability to “do as they wished.”

The two Puritan settlements in Massachusetts represented something wholly different from Jamestown, Virginia in several more ways. In Massachusetts, high literacy, low rates of disease, community effort and fruitful peace-making efforts with local tribes had produced a thriving, vibrant economy and community life. Whereas the Massachusetts settlers enjoyed two generations of fairly stable peace with local tribes (excepting a very bloody affair early on with the Pequot), the settlers in Virginia found themselves immediately and perpetually at odds with the native inhabitants. In Jamestown, disease, death, illiteracy and despair were commonplace.

One Commonality

Self government was probably the one thing which all Englishmen in the New World shared. This was both radically different and surprisingly similar to the situation in the England they had left. Seventeenth century England was the most democratic nation on earth; Englishmen expected to be represented in Parliament and had well-established rights. However, having the vote in England meant being landed, or owning land, and there simply was no more land available.

Hence, the vote in England was held by a few on behalf of all. In the new English colonies of North America, land was very attainable. While the vote in English North America was initially limited to land owners (just like in old England), proportionally far more people could vote. Those who couldn’t vote could look forward to a time when they would hold enough land to vote. Of course, early English voting in North America was more about having a say in company policy; but company policy, early on, was the only rule there was.

Where?

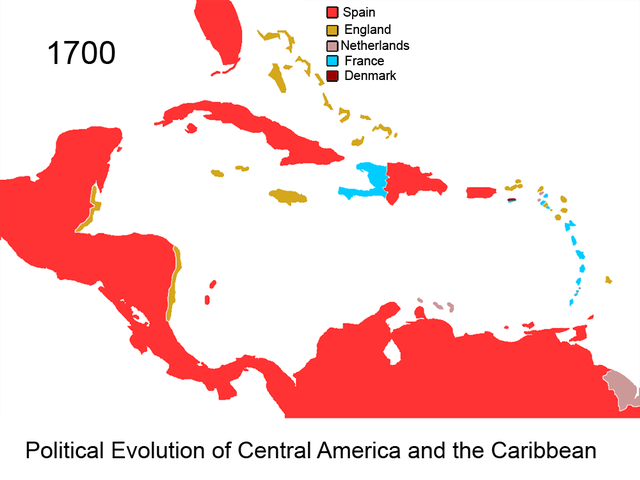

By the early 17th century, a picture of the New World began to emerge in which the three primary European powers—Spain, France, and England, controlled or influenced a large swath of the hemisphere. In the Great Lakes region, and all along the Saint Lawrence river valley, were the French and their fur-trading Huron allies. From what we now call Florida, west to California, and down into Central and South America were the Spanish.

By the end of the 17th century, most of the eastern coast of North America was colonized and dominated by the English. All three powers controlled various sugar-producing islands in and around the Caribbean.

Video: “La Purisima 00:15:16 (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Ti24ZcBo)

Motivations for English Empire Building

The motives for English empire building did not differ so much from those of Spain and France. All three sought to promote their economic welfare, their strategic positions and either a Protestant or a Catholic version of Christianity. One notable addition to the English experience was that England began empire building in the New World at the same time that a labor glut had given large numbers of the English reason to join the effort by way of emigration.

In addition, the Commercial Revolution sweeping England had created a burgeoning textile industry, which demanded an ever increasing supply of wool to keep the looms running. Landlords enclosed farmlands and evicted the peasants in favor of sheep cultivation. Colonial expansion became an outlet for this displaced peasant population.

Strategically, colonies could provide England with military bases from which to attack, defend and promote their national interests. Economically, colonies could provide raw materials, markets for manufactured goods and income through taxation—usually in the form of import and export duties. Finally, and in some sense most importantly, colonies provided a haven for those disaffected folk who found life in England intolerable for one reason or another. Overseas, it was thought, these people could complain to the trees and not cause social divisions at home in England.

Similarities between the European Powers

The French and Spanish colonizers tended to be young, single men who viewed the New World as a place from which to extract wealth and return home to an easier life. In this regard the English settlers of Jamestown, Virginia were quite similar. For most of them, earliest Virginia was a place to build a fortune and return home. Their housing was impermanent, flimsy and ramshackle. There was no motivation to erect impressive homes or cities when few, if any, intended to stay long term. As a point of reference, the first common building erected in most early Virginia settlements was the tavern—a place for governing, voting and, of course, drinking. These men valued liberty for the ability it gave them to do as they wished.

Challenges to Orthodoxy in Massachusetts

As part of the company charter, a General Court was established to make laws for the colony, establish townships and settle disputes. With rapid economic success and population growth, new towns sprang up regularly. Since Massachusetts lacked the navigable rivers of Virginia, its early settlers were road builders. Of particular importance to early Massachusetts was homogeneity; the Puritan settlers were to live and behave "as one man," without conflict, greed or dissent. The ability to "act as one man," quickly established the settlements in Massachusetts as having the highest standard of living in the world. In order to act "as one man," the vote was limited to Church members; those who tended toward individualism were "encouraged" out of the colony. This was not a colony for dissenters and refugees.

Roger Williams

One of the early dissenters was the Puritan pastor Roger Williams. Williams, a gifted linguist, had received his education in England's Cambridge University before declaring himself in dissent against the Anglican Church. His brief tenure in Massachusetts found him at odds with the Puritan authorities over his belief in "liberty of conscience" and "separation of church and state." Williams had accurately pointed out that it was liberty of conscience that had led the Puritans to the New World. Now in the New World, Williams' own conscience dictated that the Puritan authorities were in error when they asserted authority over matters both civil and religious. It was William's conviction that "on a good day religious coercion creates hypocrites; on a bad day-rivers of blood." After a series of pastorships in Salem and Plymouth, Williams was forced out by the General Court in the mid-1630s and removed to what would become Providence, Rhode Island. He purchased land from the Narragansett Indians in 1636. In 1644, a sympathetic Puritan-controlled English Parliament gave him the charter that established Rhode Island as a distinct colony. The colony would be the first to declare for "liberty of conscience" and a separation of church and state.

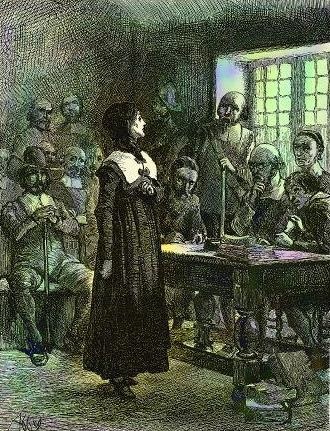

Anne Hutchinson

Another early dissenter was Anne Hutchinson. Hutchinson had a keen mind and enjoyed discussing scripture in her home. She, like Williams, also believed in a sort of liberty of conscience and claimed that she had an “inner light” by which she could understand both scripture and the leading of the Holy Spirit. The popularity of her discussions alarmed the Puritan authorities and, in 1637, she also was forced out by the General Court for holding “dangerous opinions.” Both Hutchinson and Williams believed scripture to be more authoritative than “men.” Interestingly, the Protestant Reformation, one century earlier, had justified breaking with the Catholic Church on roughly the same grounds.

Pequot War

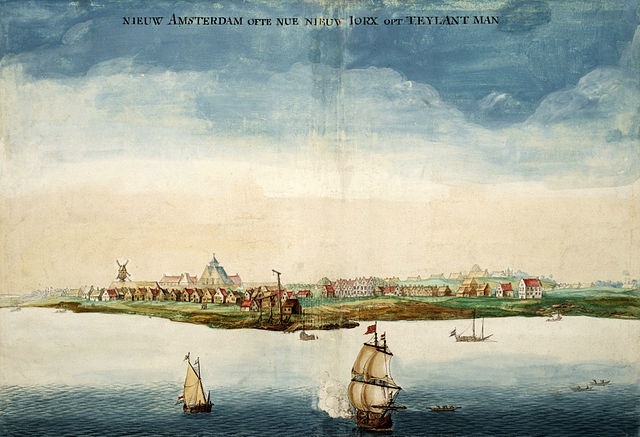

At about this same time an exceptionally bloody conflict broke out just south of Massachusetts. Approximately 100 years earlier, the Pequot Nation had forcefully pushed numerous tribes out of the region and begun aggressively subduing remaining tribes into tributary status. The Pequot began trading fur to the Dutch at New Amsterdam (later New York) which the Dutch had established in 1624 in between Virginia and Massachusetts. This meant that the Dutch and the English were in competition as neighbors in the New World and the Pequot were in competition with other local tribes to dominate the trade with these Europeans. At stake for the tribes was the ability to subdue (or the misfortune to be subdued by) rival—and vengeful—tribes with European weapons.

In two incidents, English traders, one a slaver and a pirate, the other a respected trader, were killed by tribes allied with, and suspected of allying with, the Pequot. One of these tribes (the Narragansett) was successfully placated through negotiations with Roger Williams. Neither tribe agreed to turn over the perpetrators and a combined force of Puritans from Massachusetts and the new Puritan colony of Connecticut (est. 1635) set off on a retaliatory raid which culminated in the capture and burning of the main Pequot village at Misistuck (Mystic). Hundreds of men, women and children were burned to death, or shot while attempting to flee. One Puritan leader was reported to have given thanks that “this day we have sent 600 heathen souls to hell.” Pequot domination of the region had ended. Pequot territory was distributed to friendly tribes and English settlers while Pequot survivors were sold into slavery or escaped to other tribes.

Puritan Expansion

Defeated Pequots and so-called heretics like Williams and Hutchinson were not the only ones who left Massachusetts. Orthodox Puritans, seeking better lands and opportunities, soon began leaving Massachusetts Bay Colony. News of the fertility of the Connecticut River Valley, for instance, attracted the interest of farmers having a difficult time with poor land. By the early 1630s, many were ready to brave the danger of Indian attack to obtain level ground and deep, rich soil. These new communities often eliminated church membership as a prerequisite for voting, thereby extending the franchise (vote) to ever larger numbers of men.

At the same time, other settlements began cropping up along the New Hampshire and Maine coasts, as more and more immigrants sought the land and liberty the New World seemed to offer.

New Netherland and Maryland

Hired by the Dutch East India Company, Henry Hudson in 1609 explored the area around what is now New York City and the river that bears his name, to a point probably north of present-day Albany, New York. Subsequent Dutch voyages laid the basis for their claims and early settlements in the area.

As with the French to the north, the first interest of the Dutch was the fur trade. To this end, they cultivated close relations with the Five Nations of the Iroquois, who were the key to the heartland from which the furs came. In 1617 Dutch settlers built a fort at the junction of the Hudson and the Mohawk Rivers, where Albany now stands.

Settlement on the island of Manhattan began in the early 1620s. In 1624, the island was purchased from local Native Americans for the reported price of $24. It was promptly renamed New Amsterdam.

In order to attract settlers to the Hudson River region, the Dutch encouraged a type of feudal aristocracy, known as the “patroon” system. The first of these huge estates was established in 1630 along the Hudson River. Under the patroon system, any stockholder, or patroon, who could bring 50 adults to his estate over a four-year period was given a 15-mile river-front plot, exclusive fishing and hunting privileges, and civil and criminal jurisdiction over his lands. In turn, he provided livestock, tools, and buildings. The tenants paid the patroon rent and gave him first option on surplus crops.

Further to the south, a Swedish trading company with ties to the Dutch attempted to set up its first settlement along the Delaware River three years later. Without the resources to consolidate its position, New Sweden was gradually absorbed into New Netherland, and later, Pennsylvania and Delaware.

In 1632 the Catholic Calvert family obtained a charter for land north of the Potomac River from King Charles I in what became known as Maryland. As the charter did not expressly prohibit the establishment of non-Protestant churches, the colony became a haven for Catholics. Maryland’s first town, St. Mary’s, was established in 1634 near where the Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay.

While establishing a refuge for Catholics, who faced increasing persecution in Anglican England, the Calverts were also interested in creating profitable estates. To this end, and to avoid trouble with the British government, they also encouraged Protestant immigration.

Maryland’s royal charter had a mixture of feudal and modern elements. On the one hand the Calvert family had the power to create manorial estates. On the other, they could only make laws with the consent of freemen (property holders). They found that in order to attract settlers — and make a profit from their holdings — they had to offer people farms, not just tenancy on manorial estates. The number of independent farms grew in consequence. Their owners demanded a voice in the affairs of the colony. Maryland’s first legislature met in 1635.

Colonial-Indian Relations

By 1640 the British had solid colonies established along the New England coast and the Chesapeake Bay. In between were the Dutch and the tiny Swedish community. To the west were the original Americans, then called Indians.

Sometimes friendly, sometimes hostile, the Eastern tribes were no longer strangers to the Europeans. Although Native Americans benefited from access to new technology and trade, the disease and thirst for land that the early settlers also brought posed a serious challenge to their long-established way of life.

At first, trade with the European settlers brought advantages: knives, axes, weapons, cooking utensils, fishhooks, and a host of other goods. Those Indians who traded initially had significant advantage over rivals who did not. In response to European demand, tribes such as the Iroquois began to devote more attention to fur trapping during the 17th century. Furs and pelts provided tribes the means to purchase colonial goods until late into the 18th century.

Early colonial-Native-American relations were an uneasy mix of cooperation and conflict. On the one hand, there were the exemplary relations that prevailed during the first half century of Pennsylvania’s existence. On the other were a long series of setbacks, skirmishes, and wars, which almost invariably resulted in an Indian defeat and further loss of land.

The first of the important Native- American uprisings occurred was the aforementioned Powhatan war in 1622, when some 347 whites were killed, including a number of missionaries who had just recently come to Jamestown.

White settlement of the Connecticut River region touched off the Pequot War in 1637. In 1675 King Philip, the son of the native chief who had made the original peace with the Pilgrims in 1621, attempted to unite the tribes of southern New England against further European encroachment of their lands. In the struggle, however, Philip lost his life and many Indians were sold into servitude.

The steady influx of settlers into the backwoods regions of the Eastern colonies disrupted Native-American life. As more and more game was killed off, tribes were faced with the difficult choice of going hungry, going to war, or moving and coming into conflict with other tribes to the west.

The Iroquois, who inhabited the area below lakes Ontario and Erie in northern New York and Pennsylvania, were more successful in resisting European advances. In 1570 five tribes joined to form the most complex Native-American nation of its time, the “Ho-De-No-Sau- Nee,” or League of the Iroquois. The league was run by a council made up of 50 representatives from each of the five member tribes. The council dealt with matters common to all the tribes, but it had no say in how the free and equal tribes ran their day-to- day affairs. No tribe was allowed to make war by itself. The council passed laws to deal with crimes such as murder.

The Iroquois League was a strong power in the 1600s and 1700s. It traded furs with the British and sided with them against the French in the war for the dominance of America between 1754 and 1763. The British might not have won that war otherwise.

The Iroquois League stayed strong until the American Revolution. Then, for the first time, the council could not reach a unanimous decision on whom to support. Member tribes made their own decisions, some fighting with the British, some with the colonists, some remaining neutral. As a result, everyone fought against the Iroquois. Their losses were great and the league never recovered.