Chapter 11 Reconstruction

Total Video (01:02:34)

Lincoln’s Plan for Reconstruction

The first great task confronting the victorious North — now under the leadership of Lincoln’s vice president, Andrew Johnson, a southerner who remained loyal to the Union — was to determine the status of the states that had seceded. Lincoln had already set the stage. In his view, the people of the Southern states had never legally seceded; they had been misled by some disloyal citizens into a defiance of federal authority. And since the war was the act of individuals, the federal government would have to deal with these individuals and not with the states. Thus, in 1863 Lincoln proclaimed that if in any state 10 percent of the voters of record from 1860 would form a government loyal to the U.S. Constitution and would acknowledge obedience to the laws of the Congress and the proclamations of the president, he would recognize the government so created as the state’s legal government.

Congress rejected this plan. Many Republicans feared it would simply entrench former rebels in power. They also challenged Lincoln’s right to deal with the rebel states without consultation. Some members of Congress advocated severe punishment for all the seceded states; others simply felt the war would have been in vain if the old Southern establishment was restored to power. Yet even before the war was wholly over, new loyalist governments had been set up in Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

Freedmen and the 13th Amendment

To deal with one of its major concerns — the condition of former slaves — Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau in March 1865 to act as guardian over African Americans and guide them toward self-support. And in December of that year, Congress ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery.

Play Video (00:03:21) The Presidents: Johnson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/play/2SBB2A)

Johnson’s Reconstruction

Throughout the summer of 1865 Johnson proceeded to carry out Lincoln’s reconstruction program, with minor modifications. By presidential proclamation he appointed a governor for each of the former Confederate states and freely restored political rights to many Southerners through use of presidential pardons.

In due time conventions were held in each of the former Confederate states to repeal the ordinances of secession, repudiate the war debt, and draft new state constitutions. Eventually a native Unionist became governor in each state with authority to convene a convention of loyal voters. Johnson called upon each convention to invalidate secession, abolish slavery, repudiate all debts that went to aid the Confederacy, and ratify the 13th Amendment. By the end of 1865, this process was completed, with a few exceptions.

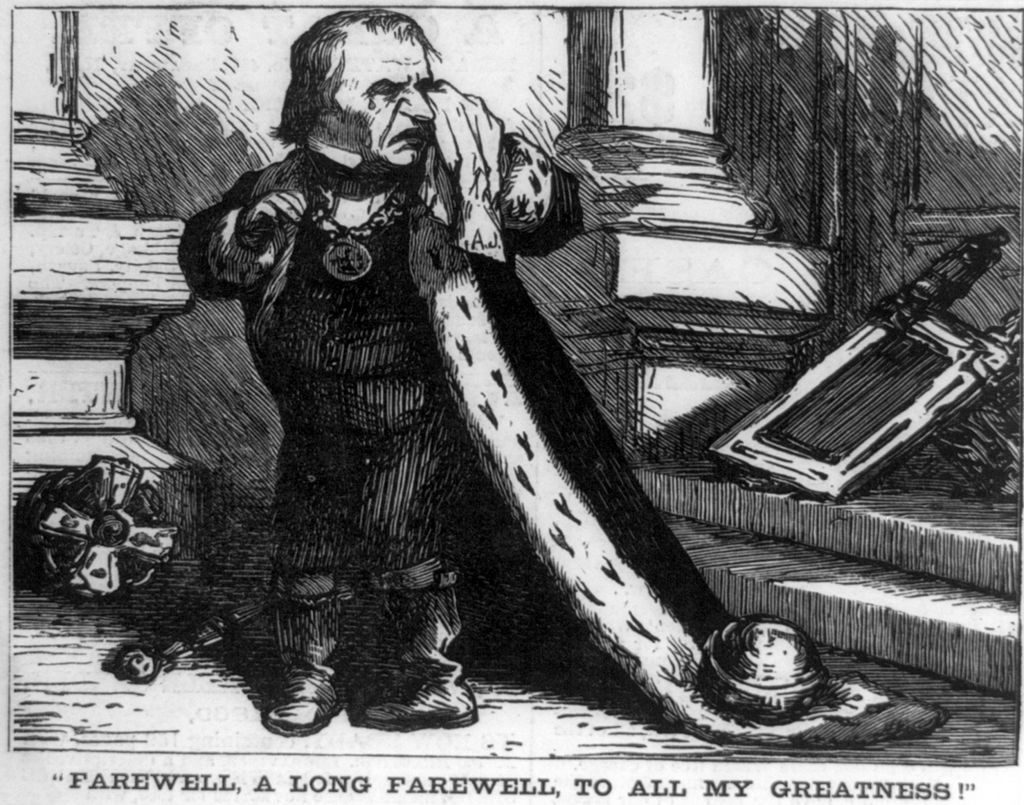

"Romeo and Mercutio" by Alfred Waud, 1868, Public Domain, via HarpWeek.

RADICAL (congressional) RECONSTRUCTION

Both Lincoln and Johnson had foreseen that the Congress would have the right to deny Southern legislators seats in the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives, under the clause of the Constitution that says, “Each house shall be the judge of the . . . qualifications of its own members.” This came to pass when, under the leadership of Thaddeus Stevens, those congressmen called “Radical Republicans,” who were wary of a quick and easy “reconstruction,” refused to seat newly elected Southern senators and representatives. Within the next few months, Congress proceeded to work out a plan for the reconstruction of the South quite different from the one Lincoln had started and Johnson had continued.

Civil Rights

Wide public support gradually developed for those members of Congress who believed that African Americans should be given full citizenship. By July 1866, Congress had passed a civil rights bill and set up a new Freedmen’s Bureau — both designed to prevent racial discrimination by Southern legislatures. Following this, the Congress passed a 14th Amendment to the Constitution, stating that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction there-of, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” This repudiated the Dred Scott ruling, which had denied slaves their right of citizenship.

![By Thomas Nast [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2369)

By Thomas Nast [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Southern Response

All the Southern state legislatures, with the exception of Tennessee, refused to ratify the amendment, some voting against it unanimously. In addition, Southern state legislatures passed “Black Codes” to regulate the African-American freedmen. The codes differed from state to state, but some provisions were common. African Americans were required to enter into annual labor contracts, with penalties imposed in case of violation; dependent children were subject to compulsory apprenticeship and corporal punishments by masters; vagrants could be sold into private service if they could not pay severe fines.

The Radicals Clamp Down

Many Northerners interpreted the Southern response as an attempt to re-establish slavery and repudiate the hard-won Union victory in the Civil War. It did not help that Johnson, although a Unionist, was a Southern Democrat with an addiction to intemperate rhetoric and an aversion to political compromise. Republicans swept the congressional elections of 1866. Firmly in power, the Radicals imposed their own vision of Reconstruction.

In the Reconstruction Act of March 1867, Congress, ignoring the governments that had been established in the Southern states, and divided the South into five military districts, each administered by a Union general. Escape from permanent military government was open to those states that established civil governments, ratified the 14th Amendment, and adopted African-American suffrage. Supporters of the Confederacy who had not taken oaths of loyalty to the United States generally could not vote. The 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868. The 15th Amendment, passed by Congress the following year and ratified in 1870 by state legislatures, provided that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The Radical Republicans in Congress were infuriated by President Johnson’s vetoes (even though they overrode them) of legislation protecting newly freed African Americans and punishing former Confederate leaders by depriving them of the right to hold office. Congressional antipathy to Johnson was so great that, for the first time in American history, impeachment proceedings were instituted to remove the president from office.

Play Video (00:5:11) The Presidents: Johnson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43177&loid=442686)

Impeachment

Johnson’s main offense was his opposition to punitive congressional policies and the violent language he used in criticizing them. The most serious legal charge his enemies could level against him was that, despite the Tenure of Office Act (which required Senate approval for the removal of any officeholder the Senate had previously confirmed), he had removed from his Cabinet the secretary of war, a staunch supporter of the Congress. When the impeachment trial was held in the Senate, it was proved that Johnson was technically within his rights in removing the Cabinet member. Even more important, it was pointed out that a dangerous precedent would be set if the Congress were to remove a president because he disagreed with the majority of its members. The final vote was one short of the two-thirds required for conviction.

Johnson continued in office until his term expired in 1869, but Congress had established an ascendancy that would endure for the rest of the century. The Republican victor in the presidential election of 1868, former Union general Ulysses S. Grant, would enforce the reconstruction policies the Radicals in Congress had initiated.

Play Video (00:02:43) The Presidents: Grant (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/play/CP9JZG)

A Nascent Women’s Rights Movement

Almost by accident, female abolitionists stumbled into their own contest for civil rights. Pressured into accepting subservient roles or shouted down when engaged otherwise, women of antebellum America realized that their own lot bore some resemblance to that of Black Americans. Their property rights were restricted as were their social freedoms. In 1848, a national convention in Seneca Falls, New York had nearly split over Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s introduction of the demand for voting rights. With the help of Frederick Douglass, a former slave and ardent abolitionist, she was able to convince a majority at the convention that the right to vote would ensure property and other rights as well.

Most suffragettes had put aside their demands during the Civil War to aid the Union and anti-slavery causes. When the 14th Amendment introduced the word “male” into the Constitution in 1866, Stanton, Anthony, and others renewed their fight with vigor.

Play Video (00:11:44) One Woman One Vote (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=44178&loid=442691)

Government without Teeth

By June 1868, Congress had re-admitted the majority of the former Confederate states back into the Union. In many of these reconstructed states, the majority of the governors, representatives, and senators were Northern men — so-called carpetbaggers — who had gone South after the war to make their political fortunes, often in alliance with newly freed African Americans. In the legislatures of Louisiana and South Carolina, African Americans actually gained a majority of the seats.

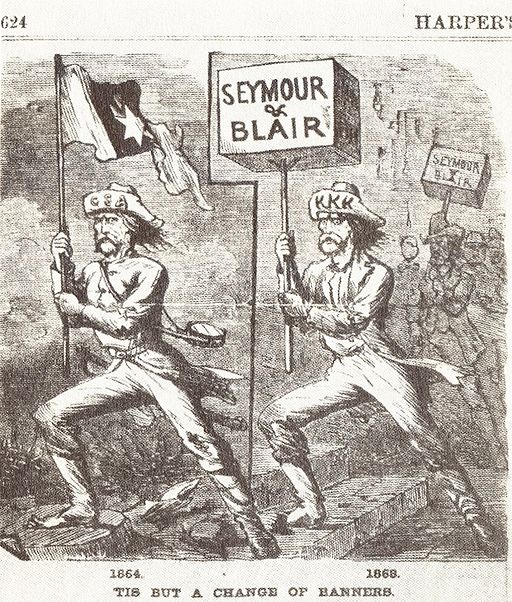

A political cartoon depicting the KKK and the Democratic Party as continuations of the Confederacy. From Harper's Weekly, 1868, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Many Southern whites, their political and social dominance threatened, turned to illegal means to prevent African Americans from gaining equality. Violence against African Americans by such extra-legal organizations as the Ku Klux Klan became more and more frequent. Increasing disorder led to the passage of Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871, severely punishing those who attempted to deprive the African-American freedmen of their civil rights.

THE END OF RECONSTRUCTION

Play Video (00:02:06)The Presidents: Grant (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/play/W4CWTE)

As time passed, it became more and more obvious that the problems of the South were not being solved by harsh laws and continuing rancor against former Confederates. Moreover, some Southern Radical state governments with prominent African-American officials appeared corrupt and inefficient. The nation was quickly tiring of the attempt to impose racial democracy and liberal values on the South with Union bayonets. In May 1872, Congress passed a general Amnesty Act, restoring full political rights to all but about 500 former rebels.

Gradually Southern states began electing members of the Democratic Party into office, ousting carpetbagger governments and intimidating African Americans from voting or attempting to hold public office. By 1876 the Republicans remained in power in only three Southern states.

Play Video (00:08:00) Hayes (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43177&loid=442692)

A New Status Quo in the South

As part of the bargaining that resolved the disputed presidential elections that year in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republicans promised to withdraw federal troops that had propped up the remaining Republican governments. In 1877 Hayes kept his promise, tacitly abandoning federal responsibility for enforcing blacks’ civil rights.

!["Colored Waiting Room" sign from segregationist era United States. By Esther Bubley [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2373)

"Colored Waiting Room" sign from segregationist era United States. By Esther Bubley [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The South was still a region devastated by war, burdened by debt caused by misgovernment, and demoralized by a decade of racial warfare. Unfortunately, the pendulum of national racial policy swung from one extreme to the other. A federal government that had supported harsh penalties against Southern white leaders now tolerated new and humiliating kinds of discrimination against African Americans. The last quarter of the 19th century saw a profusion of “Jim Crow” laws in Southern states that segregated public schools, forbade or limited African-American access to many public facilities such as parks, restaurants, and hotels, and denied most blacks the right to vote by imposing poll taxes and arbitrary literacy tests. “Jim Crow” is a term derived from a song in an 1828 minstrel show where a white man first performed in “blackface.”

Historians have tended to judge Reconstruction harshly, as a murky period of political conflict, corruption, and regression that failed to achieve its original high-minded goals and collapsed into a sinkhole of virulent racism. Slaves were granted freedom, but the North completely failed to address their economic needs. The Freedmen’s Bureau was unable to provide former slaves with political and economic opportunity. Union military occupiers often could not even protect them from violence and intimidation. Indeed, federal army officers and agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau were often racists themselves. Without economic resources of their own, many Southern African Americans were forced to become tenant farmers on land owned by their former masters, caught in a cycle of poverty that would continue well into the 20th century.

Reconstruction-era governments did make genuine gains in rebuilding Southern states devastated by the war, and in expanding public services, notably in establishing tax-supported, free public schools for African Americans and whites. However, recalcitrant Southerners seized upon instances of corruption (hardly unique to the South in this era) and exploited them to bring down radical-republican regimes. The failure of Reconstruction meant that the struggle of African Americans for equality and freedom was deferred until the 20th century — when it would become a national, not just a Southern issue.

THE CIVIL WAR AND NEW PATTERNS OF AMERICAN POLITICS

The controversies of the 1850s had destroyed the Whig Party, created the Republican Party, and divided the Democratic Party along regional lines. The Civil War demonstrated that the Whigs were gone beyond recall and the Republicans were on the scene to stay. It also laid the basis for a reunited Democratic Party.

The Republicans could seamlessly replace the Whigs throughout the North and West because they were far more than a free-soil/antislavery force. Most of their leaders had started as Whigs and continued the Whig interest in federally assisted national development. The need to manage a war did not deter them from also enacting a protective tariff (1861) to foster American manufacturing, the Homestead Act (1862) to encourage Western settlement, the Morrill Act (1862) to establish “land grant” agricultural and technical colleges, and a series of Pacific Railway Acts (1862-64) to underwrite a transcontinental railway line. These measures rallied support throughout the Union from groups to whom slavery was a secondary issue and ensured the party’s continuance as the latest manifestation of a political creed that had been advanced by Alexander Hamilton and Henry Clay.

The war also laid the basis for Democratic reunification because Northern opposition to it centered in the Democratic Party. As might be expected from the party of “popular sovereignty,” some Democrats believed that full-scale war to reinstate the Union was unjustified. This group came to be known as the Peace Democrats. Their more extreme elements were called “Copperheads.”

Moreover, few Democrats, whether of the “war” or “peace” faction, believed the emancipation of the slaves was worth Northern blood. Opposition to emancipation had long been party policy. In 1862, for example, virtually every Democrat in Congress voted against eliminating slavery in the District of Columbia and prohibiting it in the territories.

Much of this opposition came from the working poor, particularly Irish and German Catholic immigrants, who feared a massive migration of newly freed African Americans to the North. They also resented the establishment of a military draft (March 1863) that disproportionately affected them. Race riots erupted in several Northern cities. The worst of these occurred in New York, July 13-16, 1863, precipitated by Democratic Governor Horatio Seymour’s condemnation of military conscription. Federal troops, who just days earlier had been engaged at Gettysburg, were sent to restore order.

The Republicans prosecuted the war with little regard for civil liberties. In September 1862, Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus and imposed martial law on those who interfered with recruitment or gave aid and comfort to the rebels. This breech of civil law, although constitutionally justified during times of crisis, gave the Democrats another opportunity to criticize Lincoln. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton enforced martial law vigorously, and many thousands — most of them Southern sympathizers or Democrats — were arrested.

Despite the Union victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in 1863, Democratic “peace” candidates continued to play on the nation’s misfortunes and racial sensitivities. Indeed, the mood of the North was such that Lincoln was convinced he would lose his re-election bid in November 1864. Largely for that reason, the Republican Party renamed itself the Union Party and drafted the Tennessee Democrat Andrew Johnson to be Lincoln’s running mate. Sherman’s victories in the South sealed the election for them.

Lincoln’s assassination, the rise of Radical Republicanism, and Johnson’s blundering leadership all played into a postwar pattern of politics in which the Republican Party suffered from overreaching in its efforts to remake the South, while the Democrats, through their criticism of Reconstruction, allied themselves with the neo-Confederate Southern white majority. Ulysses S. Grant’s status as a national hero carried the Republicans through two presidential elections, but as the South emerged from Reconstruction, it became apparent that the country was nearly evenly divided between the two parties.

The Republicans would be dominant in the industrial Northeast until the 1930s and strong in most of the rest of the country outside the South. However, their appeal as the party of strong government and national development increasingly would be perceived as one of allegiance to big business and finance.

When President Hayes ended Reconstruction, he hoped it would be possible to build the Republican Party in the South, using the old Whigs as a base and the appeal of regional development as a primary issue. By then, however, Republicanism as the South’s white majority perceived it was identified with a hated African-American supremacy. For the next three quarters of a century, the South would be solidly Democratic. For much of that time, the national Democratic Party would pay solemn deference to states’ rights while ignoring civil rights. The group that would suffer the most as a legacy of Reconstruction was the African Americans.