Chapter 12 - Growth and Transformation

![By Ross, Alexander, Best & Co., Winnipeg [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2375)

By Ross, Alexander, Best & Co., Winnipeg [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Total Video (00:44:59)

“Upon the sacredness of property, civilization itself depends.”

Industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, 1889

Between two great wars — the Civil War and the First World War — the United States of America came of age. In a period of less than 50 years it was transformed from a rural republic to an urban nation. The frontier vanished. Great factories and steel mills, transcontinental railroad lines, flourishing cities, and vast agricultural holdings marked the land. With this economic growth and affluence came corresponding problems. Nationwide, a few businesses came to dominate whole industries, either independently or in combination with others. Working conditions were often poor. Cities grew so quickly they could not properly house or govern their growing populations.

The Republican Party became increasingly associated with big business as it primarily represented a manufacturing North which had grown all the more industrialized due to the war machine it had become during the rebellion. Growing industries capitalized on advancements in steel manufacturing. As a result, steel plows would turn prairie sod; steel windmills would pump underground water to prairie farms; and steel rails would take easterners west in steel locomotives.

Forests in Michigan and points east would find their way to sawmill’s, rail stations, and eventually—prairie settlements. Meanwhile, the land’s earliest inhabitants fought to preserve a way of life they’d known since at least the 1500s.

![The Pacific tourist - Williams' illustrated trans-continental guide of travel, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean (1877)

By Internet Archive Book Images [No restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/7734)

Image of Train along side an old windmill

TECHNOLOGY AND CHANGE

![homas Edison and his early phonograph

Thomas Edison and his early phonograph. By Levin C. Handy [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2376)

homas Edison and his early phonograph Thomas Edison and his early phonograph. By Levin C. Handy [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“The Civil War,” says one writer, “cut a wide gash through the history of the country; it dramatized in a stroke the changes that had begun to take place during the preceding 20 or 30 years. ... ” War needs had enormously stimulated manufacturing, speeding an economic process based on the exploitation of iron, steam, and electric power, as well as the forward march of science and invention. In the years before 1860, 36,000 patents were granted; in the next 30 years, 440,000 patents were issued, and in the first quarter of the 20th century, the number reached nearly a million.

As early as 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse had perfected electrical telegraphy; soon afterward distant parts of the continent were linked by a network of poles and wires. In 1876 Alexander Graham Bell exhibited a telephone instrument; within half a century, 16 million telephones would quicken the social and economic life of the nation. The growth of business was hastened by the invention of the typewriter in 1867, the adding machine in 1888, and the cash register in 1897. The linotype composing machine, invented in 1886, and rotary press and paper folding machinery made it possible to print 240,000 eight-page newspapers in an hour. Thomas Edison’s incandescent light bulb eventually lit millions of homes. The talking machine, or phonograph, was perfected by Edison, who, in conjunction with George Eastman, also helped develop the motion picture. These and many other applications of science and ingenuity resulted in a new level of productivity in almost every field.

Electricity

While known for over a century, electricity had not been meaningfully harnessed until Thomas Edison’s light bulb in 1880. The impact on all aspects of life cannot be overstated. At work, where fire from oil lanterns was an ever-present fear, longer hours and night shifts became regular fixtures. Off work, nightlife became a permanent part of larger cities and the first home entertainment systems --light bulbs-- allowed families to read in relative safety. The presence of electricity in homes spurred a demand for consumer goods which would eventually lead to the consumer economy of today.

!["The Breakers garden view," by Skip Plitt - C'ville Photography (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2377)

"The Breakers garden view," by Skip Plitt - C'ville Photography (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Robber Barons

The fabulous wealth of the Robber Barons is legendary, and the late 1800s has been labeled the “Gilded Age” as a result. These were the men who lived in opulent mansions whose income came from the factories, railroads, mines, and wells which made up the American economy of the late 1800s. The usual success story involved both horizontal and vertical integration of an entrepreneur’s operation.

![Oil wells in Cygnet, Ohio, 1885. By Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2378)

Oil wells in Cygnet, Ohio, 1885. By Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Horizontal and Vertical Integration

For example, a successful oil well owner might integrate the operation horizontally by buying up competing wells. He might then integrate vertically by buying a pipeline operation, shipping operations, and processing facilities. In this way, as well as through the use of pools (price-fixing agreements between competitors) and holding companies (one company buying up shares in other companies), steel, oil, and railroad giants emerged to stride across the U.S. economy like titans.

Concurrently, the nation’s basic industry — iron and steel — forged ahead, protected by a high tariff. The iron industry moved westward as geologists discovered new ore deposits, notably the great Mesabi range at the head of Lake Superior, which became one of the largest producers in the world. Easy and cheap to mine, remarkably free of chemical impurities, Mesabi ore could be processed into steel of superior quality at about one-tenth the previously prevailing cost.

Re-thinking how goods are made

Post Civil War industries employed scientific-management principles and military-style hierarchy with centralized command structures. By applying the time and motion studies of Frederick Taylor, railroads and other industries were able to squeeze more labor out of fewer people and create repetitive jobs which required less skill, thus making workers easily replaceable like a wheel in a machine. This conveniently led to an application of Darwin’s “survival of the fittest” to social structures. Clearly, the less competitive businesses would not last long. Because businesses wanted to survive and laborers needed to survive, the pressure to perform intensified. This overhaul of how goods were produced also marked the shift from a self-reliant, self-employed citizenry to a job-reliant, other-employed army of workers. This army, however, could and did vote with their feet and, on occasion, their fists.

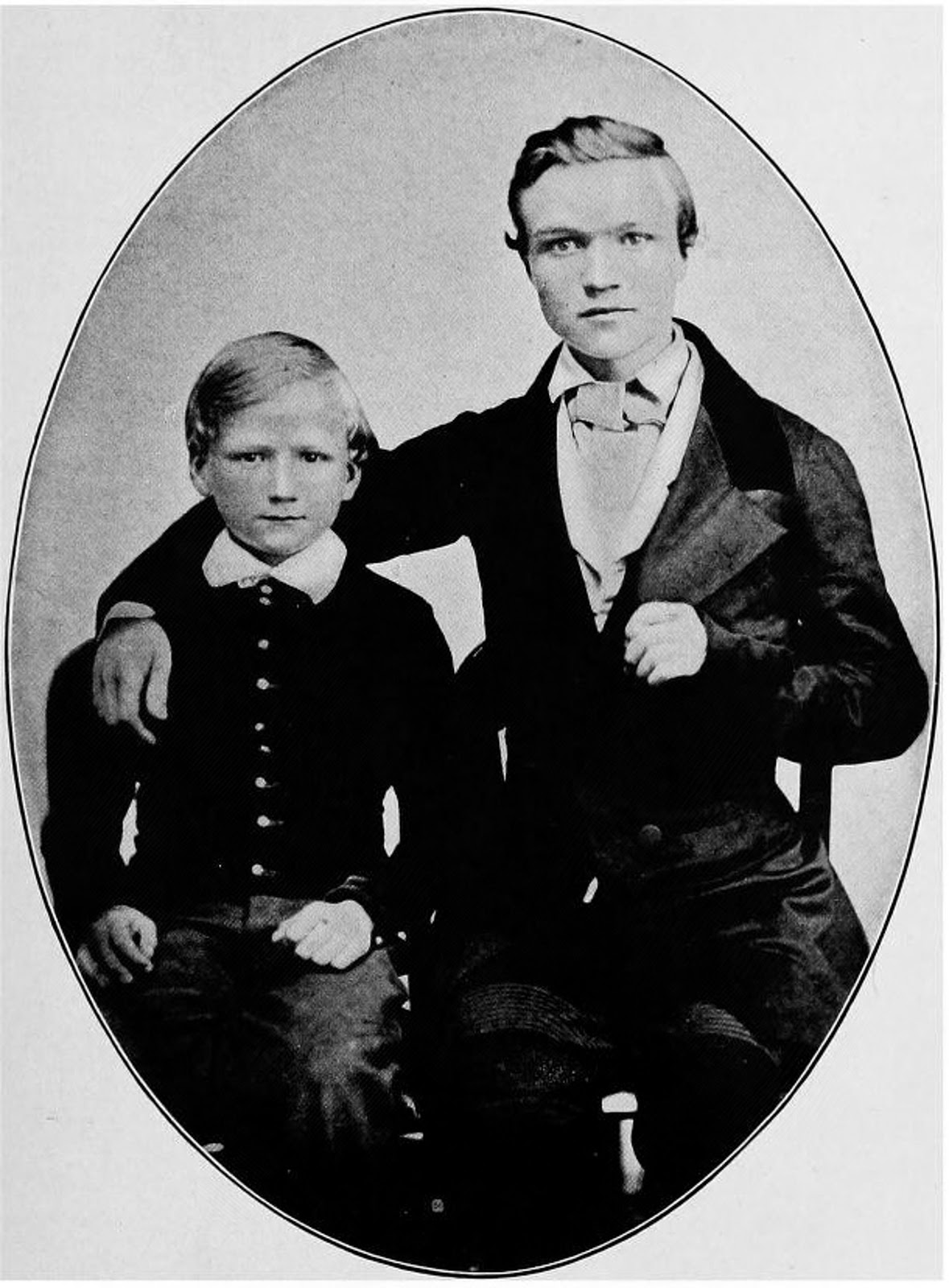

CARNEGIE AND THE ERA OF STEEL

Andrew Carnegie at age 16 (right), with his brother Thomas. "Project Gutenberg eText 17976". Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Andrew Carnegie was largely responsible for the great advances in steel production. Carnegie, who came to America from Scotland as a child of 12, progressed from bobbin boy in a cotton factory to a job in a telegraph office, then to a job on the Pennsylvania Railroad. Before he was 30 years old he had made shrewd and farsighted investments, which by 1865 were concentrated in iron. Within a few years, he had organized or had stock in companies making iron bridges, rails, and locomotives. Ten years later, he built the nation’s largest steel mill on the Monongahela River in Pennsylvania. He acquired control not only of new mills, but also of coke and coal properties, iron ore from Lake Superior, a fleet of steamers on the Great Lakes, a port town on Lake Erie, and a connecting railroad. His business, allied with a dozen others, commanded favorable terms from railroads and shipping lines. Nothing comparable in industrial growth had ever been seen in America before.

Though Carnegie long dominated the industry, he never achieved a complete monopoly over the natural resources, transportation, and industrial plants involved in the making of steel. In the 1890s, new companies challenged his preeminence. He would be persuaded to merge his holdings into a new corporation that would embrace most of the important iron and steel properties in the nation.

CORPORATIONS AND CITIES

![Nursery Rhymes for Infant Industries, No. 15. By Frederick Opper/W.R. Hearst [Public domain], via Library of Congress.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2380)

Nursery Rhymes for Infant Industries, No. 15. By Frederick Opper/W.R. Hearst [Public domain], via Library of Congress.

The United States Steel Corporation, which resulted from this merger in 1901, illustrated a process under way for 30 years: the combination of independent industrial enterprises into federated or centralized companies. Beginning during the Civil War, the trend gathered momentum after the 1870s, as businessmen began to fear that overproduction would lead to declining prices and falling profits. They realized that if they could control both production and markets, they could bring competing firms into a single organization. The “corporation” and the “trust” were developed to achieve these ends.

Corporations, Trusts and Holding Companies

Corporations, making available a deep reservoir of capital and giving business enterprises permanent life and continuity of control, attracted investors both by their anticipated profits and by their limited liability in case of business failure. The trusts were in effect combinations of corporations whereby the stockholders of each placed stocks in the hands of trustees. (The “trust” as a method of corporate consolidation soon gave way to the holding company, but the term stuck.) Trusts made possible large-scale combinations, centralized control and administration, and the pooling of patents. Their larger capital resources provided power to expand, to compete with foreign business organizations, and to drive hard bargains with labor, which was beginning to organize effectively. They could also exact favorable terms from railroads and exercise influence in politics.

The Standard Oil Company, founded by John D. Rockefeller, was one of the earliest and strongest corporations, and was followed rapidly by other combinations — in cottonseed oil, lead, sugar, tobacco, and rubber. Soon aggressive individual businessmen began to mark out industrial domains for themselves. Four great meat packers, chief among them Philip Armour and Gustavus Swift, established a beef trust. Cyrus McCormick achieved preeminence in the reaper business. A 1904 survey showed that more than 5,000 previously independent concerns had been consolidated into some 300 industrial trusts.

The trend toward amalgamation extended to other fields, particularly transportation and communications. Western Union, dominant in telegraphy, was followed by the Bell Telephone System and eventually by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company. In the 1860s, Cornelius Vanderbilt had consolidated 13 separate railroads into a single 500-mile line connecting New York City and Buffalo. During the next decade he acquired lines to Chicago, Illinois, and Detroit, Michigan, establishing the New York Central Railroad. Soon the major railroads of the nation were organized into trunk lines and systems directed by a handful of men.

![Appleton's Railway Map of the United States and Canada 1871. Flickr upload by William Creswell [Public domain or CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2381)

Appleton's Railway Map of the United States and Canada 1871. Flickr upload by William Creswell [Public domain or CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Growth of Cities

In this new industrial order, the city was the nerve center, bringing to a focus all the nation’s dynamic economic forces: vast accumulations of capital, business, and financial institutions, spreading railroad yards, smoky factories, armies of manual and clerical workers. Villages, attracting people from the countryside and from lands across the sea, grew into towns and towns into cities almost overnight. In 1830 only one of every 15 Americans lived in communities of 8,000 or more; in 1860 the ratio was nearly one in every six; and n 1890 three in every 10. No single city had as many as a million inhabitants in 1860; but 30 years later New York had a million and a half; Chicago, Illinois, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, each had over a million. In these three decades, Philadelphia and Baltimore, Maryland, doubled in population; Kansas City, Missouri, and Detroit, Michigan, grew fourfold; Cleveland, Ohio, sixfold; Chicago, tenfold. Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Omaha, Nebraska, and many communities like them — hamlets when the Civil War began — increased 50 times or more in population.

RAILROADS, REGULATIONS, AND THE TARIFF

Video: (00:13:17) The Presidents: Garfield and Arthur (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43177&loid=442763)

The Railroad industry accelerated due to government support and intrinsic advantages. The Land Grant Bill of 1862 awarded huge swaths of western land to Railroads. The rails were laid through this land with the remaining real estate sold to settlers. The profit from these sales paid for the track-laying, while the settlement along railroad lines guaranteed future business in freight to and from these frontier settlements. Railroads also had the advantages of not being ice-bound during winter and greater flexibility of location as they could go where canals and rivers could not. It was the Railroad which gave us standardized time zones, boosted a nascent tourism industry and served as an industry multiplier by enabling the mass movement of people, parts, goods and machines. If the movement of settlers to the West was large during the time of the prairie schooner, it quickly became a torrent with the introduction of rail travel. New settlers meant new cities, new industries within those cities and increasing demand for the goods shipped on the rails.

![Railroad crew levels the track bed at Sweet Briar, West of the Missouri River in 1879. Author Unknown [Public Domain] via NDStudies.gov.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2382)

Railroad crew levels the track bed at Sweet Briar, West of the Missouri River in 1879. Author Unknown [Public Domain] via NDStudies.gov.

Shipping Costs

Railroads were especially important to the expanding nation, and their practices were often criticized. Rail lines extended cheaper freight rates to large shippers by rebating a portion of the charge, thus disadvantaging small shippers. Freight rates also frequently were not proportionate to distance traveled; competition usually held down charges between cities with several rail connections. Rates tended to be high between points served by only one line. Thus it cost less to ship goods 800 miles from Chicago to New York than to places only a hundred miles from Chicago. Moreover, to avoid competition rival companies sometimes divided (“pooled”) the freight business according to a prearranged scheme that placed the total earnings in a common fund for distribution.

Popular resentment at these practices stimulated state efforts at regulation, but the problem was national in character. Freight customers demanded congressional action. In 1887 President Grover Cleveland signed the Interstate Commerce Act, which forbade excessive charges, pools, rebates, and rate discrimination. It created an Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to oversee the act, but gave it little enforcement power. In the first decades of its existence, virtually all the ICC’s efforts at regulation and rate reductions failed to pass judicial review.

Video:(00:07:18) The Presidents: Cleveland (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43178&loid=442764)

Tariff Reform

Another practice which many Americans had come to view as onerous was the protective tariff on imported goods. Such tariffs had come to be accepted as permanent national policy under the Republican presidents who dominated the politics of the era. Cleveland, a conservative Democrat, regarded tariff protection as an unwarranted subsidy to big business, giving the trusts pricing power to the disadvantage of ordinary Americans. Reflecting the interests of their Southern base, the Democrats had reverted to their pre-Civil War opposition to protection and advocacy of a “tariff for revenue only.”

Video (00:03:54) The Presidents: Harrison (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43178&loid=442765)

Cleveland, narrowly elected in 1884, was unsuccessful in achieving tariff reform during his first term. He made the issue the keynote of his campaign for reelection, but Republican candidate Benjamin Harrison, a defender of protectionism, won in a close race. In 1890, the Harrison administration, fulfilling its campaign promises, achieved passage of the McKinley tariff, which increased the already high rates. Blamed for high retail prices, the McKinley duties triggered widespread dissatisfaction, led to Republican losses in the 1890 elections, and paved the way for Cleveland’s return to the presidency in the 1892 election.

Video (00:03:33) The Presidents: Cleveland's Second Term (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43178&loid=442766)

During this period, public antipathy toward the trusts increased. The nation’s gigantic corporations were subjected to bitter attack through the 1880s by reformers such as Henry George and Edward Bellamy. The Sherman Antitrust Act, passed in 1890, forbade all combinations in restraint of interstate trade and provided several methods of enforcement with severe penalties. Couched in vague generalities, the law accomplished little immediately after its passage. But a decade later, President Theodore Roosevelt would use it vigorously.

Video (00:08:03): Little House(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/m4TCz73Y)

REVOLUTION IN AGRICULTURE

As farmers arrived in Kansas, Nebraska, and points further west, they found that life went from rough to intolerable. What appeared to be the blessings of higher yields due to windmills, better plows, and reaping machines ended up driving prices lower. To turn a profit, farmers took out loans to put more land in production and buy the latest machinery to work the land more efficiently. This, in turn, increased yields further, drove prices lower, and resulted in an endless cycle of debt for prairie farmers. Though farmers had begun their homesteads and settlements in local competition with each other, the arrival of a railroad quickly connected them to the rest of the nation’s markets and, --when a railroad had access to a sea port-- the world. Farmers soon demanded legislation that would protect them from railroads to the East and Indians to the West.

Video (00:01:13): “Little House on the Prairie" (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/p6PGe45Y)

![Reaper, Patented June 21, 1834. By C. H. McCormick [Public domain], via United States Patent and Trademark Office.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2383)

Reaper, Patented June 21, 1834. By C. H. McCormick [Public domain], via United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Despite great gains in industry, agriculture remained the nation’s basic occupation. The revolution in agriculture — paralleling that in manufacturing after the Civil War — involved a shift from hand labor to machine farming, and from subsistence to commercial agriculture. Between 1860 and 1910, the number of farms in the United States tripled, increasing from two million to six million, while the area farmed more than doubled from 400 million to 850 million acres. Between 1860 and 1890, the production of such basic commodities as wheat, corn, and cotton outstripped all previous figures in the United States. In the same period, the nation’s population more than doubled, with the largest growth in the cities. But the American farmer grew enough grain and cotton, raised enough beef and pork, and clipped enough wool not only to supply American workers and their families but also to create ever-increasing surpluses.

Several factors accounted for this extraordinary achievement. One was the expansion into the West. Another was a technological revolution. The farmer of 1800, using a hand sickle, could hope to cut half an acre of wheat a day. With the cradle, 30 years later, he might cut two acres. In 1840 Cyrus McCormick performed a miracle by cutting 6 acres a day with the reaper, a machine he had been developing for nearly 10 years. He headed west to the young prairie town of Chicago, where he set up a factory — and by 1860 sold a quarter of a million reapers. Other farm machines were developed in rapid succession: the automatic wire binder, the threshing machine, and the reaper-thresher or combine. Mechanical planters, cutters, huskers, and shellers appeared, as did cream separators, manure spreaders, potato planters, hay driers, poultry incubators, and a hundred other inventions.

Agricultural Colleges

Scarcely less important than machinery in the agricultural revolution was science. In 1862 the Morrill Land Grant College Act allotted public land to each state for the establishment of agricultural and industrial colleges. These were to serve both as educational institutions and as centers for research in scientific farming. Congress subsequently appropriated funds for the creation of agricultural experiment stations throughout the country and granted funds directly to the Department of Agriculture for research purposes. By the beginning of the new century, scientists throughout the United States were at work on a wide variety of agricultural projects.

One of these scientists, Mark Carleton, traveled for the Department of Agriculture to Russia. There he found and exported to his homeland the rust- and drought-resistant winter wheat that now accounts for more than half the U.S. wheat crop. Another scientist, Marion Dorset, conquered the dreaded hog cholera, while still another, George Mohler, helped prevent hoof-and-mouth disease. From North Africa, one researcher brought back Kaffir corn; from Turkestan, another imported the yellow-flowering alfalfa. Luther Burbank in California produced scores of new fruits and vegetables; in Wisconsin, Stephen Babcock devised a test for determining the butterfat content of milk; at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, George Washington Carver found hundreds of new uses for the peanut, sweet potato, and soybean.

![George Washington Carver

Frances Benjamin Johnston [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2384)

George Washington Carver Frances Benjamin Johnston [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In varying degrees, the explosion in agricultural science and technology affected farmers all over the world, raising yields, squeezing out small producers, and driving migration to industrial cities. Railroads and steamships, moreover, began to pull regional markets into one large world market with prices instantly communicated by trans-Atlantic cable as well as ground wires. Good news for urban consumers, falling agricultural prices threatened the livelihood of many American farmers and touched off a wave of agrarian discontent.

"J. P. Morgan striking photographer with cane." Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

J.P. MORGAN AND FINANCE CAPITALISM

The rise of American industry required more than great industrialists. Big industry required big amounts of capital; headlong economic growth required foreign investors. John Pierpont (J.P.) Morgan was the most important of the American financiers who underwrote both requirements.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Morgan headed the nation’s largest investment banking firm. It brokered American securities to wealthy elites at home and abroad. Since foreigners needed assurance that their investments were in a stable currency, Morgan had a strong interest in keeping the dollar tied to its legal value in gold. In the absence of an official U.S. central bank, he became the de facto manager of the task.

From the 1880s through the early 20th century, Morgan and Company not only managed the securities that underwrote many important corporate consolidations, it actually originated some of them. The most stunning of these was the U.S. Steel Corporation, which combined Carnegie Steel with several other companies. Its corporate stock and bonds were sold to investors at the then-unprecedented sum of $1.4 billion.

Morgan originated, and made large profits from, numerous other mergers. Acting as primary banker to numerous railroads, moreover, he effectively muted competition among them. His organizational efforts brought stability to American industry by ending price wars to the disadvantage of farmers and small manufacturers, who saw him as an oppressor. In 1901, when he established the Northern Securities Company to control a group of major railroads, President Theodore Roosevelt authorized a successful Sherman Antitrust Act suit to break up the merger.

Acting as an unofficial central banker, Morgan took the lead in supporting the dollar during the economic depression of the mid-1890s by marketing a large government bond issue that raised funds to replenish Treasury gold supplies. At the same time, his firm undertook a short-term guarantee of the nation’s gold reserves. In 1907, he took the lead in organizing the New York financial community to prevent a potentially ruinous string of bankruptcies. In the process, his own firm acquired a large independent steel company, which it amalgamated with U.S. Steel. President Roosevelt personally approved the action in order to avert a serious depression.

By then, Morgan’s power was so great that most Americans instinctively distrusted and disliked him. With some exaggeration, reformers depicted him as the director of a “money trust” that controlled America. By the time of his death in 1913, the country was in the final stages of at last reestablishing a central bank, the Federal Reserve System, that would assume much of the responsibility he had exercised unofficially.

THE DIVIDED SOUTH

After Reconstruction, Southern leaders pushed hard to attract industry. States offered large inducements and cheap labor to investors to develop the steel, lumber, tobacco, and textile industries. Yet in 1900 the region’s percentage of the nation’s industrial base remained about what it had been in 1860. Moreover, the price of this drive for industrialization was high: Disease and child labor proliferated in Southern mill towns. Thirty years after the Civil War, the South was still poor, overwhelmingly agrarian, and economically dependent. Moreover, its race relations reflected not just the legacy of slavery, but what was emerging as the central theme of its history — a determination to enforce white supremacy at any cost.

The Supreme Court in the South

Intransigent white Southerners found ways to assert state control to maintain white dominance. Several Supreme Court decisions also bolstered their efforts by upholding traditional Southern views of the appropriate balance between national and state power.

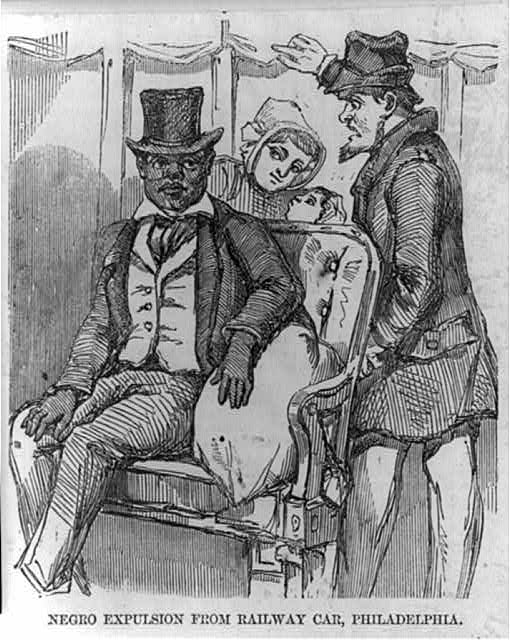

"Negro expulsion from railway car, Philadelphia," 1856. Public Domain via Library of Congress.

In 1873 the Supreme Court found that the 14th Amendment (citizenship rights not to be abridged) conferred no new privileges or immunities to protect African Americans from state power. In 1883, furthermore, it ruled that the 14th Amendment did not prevent individuals, as opposed to states, from practicing discrimination. And in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Court found that “separate but equal” public accommodations for African Americans, such as trains and restaurants, did not violate their rights. Soon the principle of segregation by race extended into every area of Southern life, from railroads to restaurants, hotels, hospitals, and schools. Moreover, any area of life that was not segregated by law was segregated by custom and practice. Further curtailment of the right to vote followed. Periodic lynchings by mobs underscored the region’s determination to subjugate its African- American population. This system of oppression and segregation came to be known as “Jim Crow” after a popular minstrel song which stereotyped post-Civil War blacks.

![Washington (left) by Unknown photographer, cropped by User:Connormah [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; and and Du Bois (right) by Addison N. Scurlock [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2386)

Washington (left) by Unknown photographer, cropped by User:Connormah [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; and and Du Bois (right) by Addison N. Scurlock [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Faced with pervasive discrimination, many African Americans followed Booker T. Washington, who counseled them to focus on modest economic goals and to accept temporary social discrimination. Others, led by the African-American intellectual W.E.B. DuBois, wanted to challenge segregation through political action. But with both major political parties uninterested in the issue and scientific theory of the time generally accepting black inferiority, calls for racial justice attracted little support.

THE LAST FRONTIER

![Work of the United States government (http://www.history.army.mil/books/amh/Map14-35.jpg) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2388)

Work of the United States government (http://www.history.army.mil/books/amh/Map14-35.jpg) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In 1865 the frontier line generally followed the western limits of the states bordering the Mississippi River, but bulged outward beyond the eastern sections of Texas, Kansas, and Nebraska. Then, running north and south for nearly 1,000 miles, loomed huge mountain ranges, many rich in silver, gold, and other metals. To their west, plains and deserts stretched to the wooded coastal ranges and the Pacific Ocean. Apart from the settled districts in California and scattered outposts, the vast inland region was populated by Native Americans: among them the Great Plains tribes — Sioux and Blackfoot, Pawnee and Cheyenne — and the Indian cultures of the Southwest, including Apache, Navajo, and Hopi.

![“Cheyenne: Stump Horn and family showing Horse Travois.” Author unknown (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2389)

“Cheyenne: Stump Horn and family showing Horse Travois.” Author unknown (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

![“United States Population Density 1890.” By Rand McNally [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0], via David Rumsey Map Collection.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2390)

“United States Population Density 1890.” By Rand McNally [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0], via David Rumsey Map Collection.

A mere quarter-century later, virtually all this country had been carved into states and territories. Miners had ranged over the whole of the mountain country, tunneling into the earth, establishing little communities in Nevada, Montana, and Colorado. Cattle ranchers, taking advantage of the enormous grasslands, had laid claim to the huge expanse stretching from Texas to the upper Missouri River. Sheep herders had found their way to the valleys and mountain slopes. Farmers sank their plows into the plains and closed the gap between the East and West. By 1890 the frontier line had disappeared.

Settlement was spurred by the Homestead Act of 1862, which granted free farms of 160 acres to citizens who would occupy and improve the land. Unfortunately for the would-be farmers, much of the Great Plains was suited more for cattle ranching than farming, and by 1880 nearly 55,300,000 acres of “free” land were in the hands of cattlemen or the railroads.

Trans-continental Railroad

In 1862 Congress also voted a charter to the Union Pacific Railroad, which pushed westward from Council Bluffs, Iowa, using mostly the labor of ex-soldiers and Irish immigrants. At the same time, the Central Pacific Railroad began to build eastward from Sacramento, California, relying heavily on Chinese immigrant labor. The whole country was stirred as the two lines steadily approached each other, finally meeting on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Point in Utah. The months of laborious travel hitherto separating the two oceans was now cut to about six days. The continental rail network grew steadily; by 1884 four great lines linked the central Mississippi Valley area with the Pacific.

![Transcontinental Railroad Lines, 1887. By United States Pacific Railway Commission. Digital image reconstruction and restoration is by Centpacrr at en.wikipedia (DigitalImageServices.com) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2391)

Transcontinental Railroad Lines, 1887. By United States Pacific Railway Commission. Digital image reconstruction and restoration is by Centpacrr at en.wikipedia (DigitalImageServices.com) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Video Gold Rush (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Ex56DbPq)

Mining and Ranching

The first great rush of population to the Far West was drawn to the mountainous regions, where gold was found in California in 1848, in Colorado and Nevada 10 years later, in Montana and Wyoming in the 1860s, and in the Black Hills of the Dakota country in the 1870s. Miners opened up the country, established communities, and laid the foundations for more permanent settlements. Eventually, however, though a few communities continued to be devoted almost exclusively to mining, the real wealth of Montana, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, and California proved to be in the grass and soil. Cattle-raising, long an important industry in Texas, flourished after the Civil War, when enterprising men began to drive their Texas longhorn cattle north across the open public land. Feeding as they went, the cattle arrived at railway shipping points in Kansas, larger and fatter than when they started. The annual cattle drive became a regular event; for hundreds of miles, trails were dotted with herds moving northward.

!["Cattle Round Up." Close view of a steer downed for branding, ca. 1896--99, Arizona Territory. Author unknown (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2392)

"Cattle Round Up." Close view of a steer downed for branding, ca. 1896--99, Arizona Territory. Author unknown (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Next, immense cattle ranches appeared in Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakota territory. Western cities flourished as centers for the slaughter of cattle and dressing of meat. The cattle boom peaked in the mid-1880s. By then, not far behind the rancher creaked the covered wagons of the farmers bringing their families, their draft horses, cows, and pigs. Under the Homestead Act they staked their claims and fenced them with a new invention, barbed wire. Ranchers were ousted from lands they had roamed without legal title.

Video (00:06:12):Oregon Trail/Gold Country (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/q9C3Mfo2&sa=D&ust=1482417433410000&usg=AFQjCNFGLJ2FWzd6gIpMCd8P_r_xaWd6TQ)

![“Oregon Trail Reenactment.” Author unknown, (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2393)

“Oregon Trail Reenactment.” Author unknown, (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Ranching and the cattle drives gave American mythology its last icon of frontier culture — the cowboy. The reality of cowboy life was one of grueling hardship. As depicted by writers like Zane Grey and movie actors such as John Wayne, the cowboy was a powerful mythological figure, a bold, virtuous man of action. Not until the late 20th century did a reaction set in. Historians and filmmakers alike began to depict “the Wild West” as a sordid place, peopled by characters more apt to reflect the worst, rather than the best, in human nature.

![By Ross, Alexander, Best & Co., Winnipeg [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/2374)

By Ross, Alexander, Best & Co., Winnipeg [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Video (00:02:09): Stock Yards (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/y9EXq5b2)