Chapter 15 - War, Prosperity, and Collapse

Total Video (01:44:36)

“The chief business of the American people is business.” President Calvin Coolidge, 1925

WAR AND NEUTRAL RIGHTS

The end of the Progressive Era, the end of unbridled optimism, indeed, the end of the world, had apparently arrived in August of 1914. German and British visions of empire were coming into conflict in Africa, Asia and the South Pacific. As western nations embraced nationalism (the belief in the superiority of their own cultures) and modernized their military machines, a series of entangling European alliances developed to “balance” the powers of the European continent. England, France and Russia constituted the “Allied” powers while Germany, Austria and Turkey formed the “Central” powers. An attack on one was to be considered an attack on all according to most treaty arrangements, hence, Europe found itself sitting on a powder keg of tension in the summer of 1914.

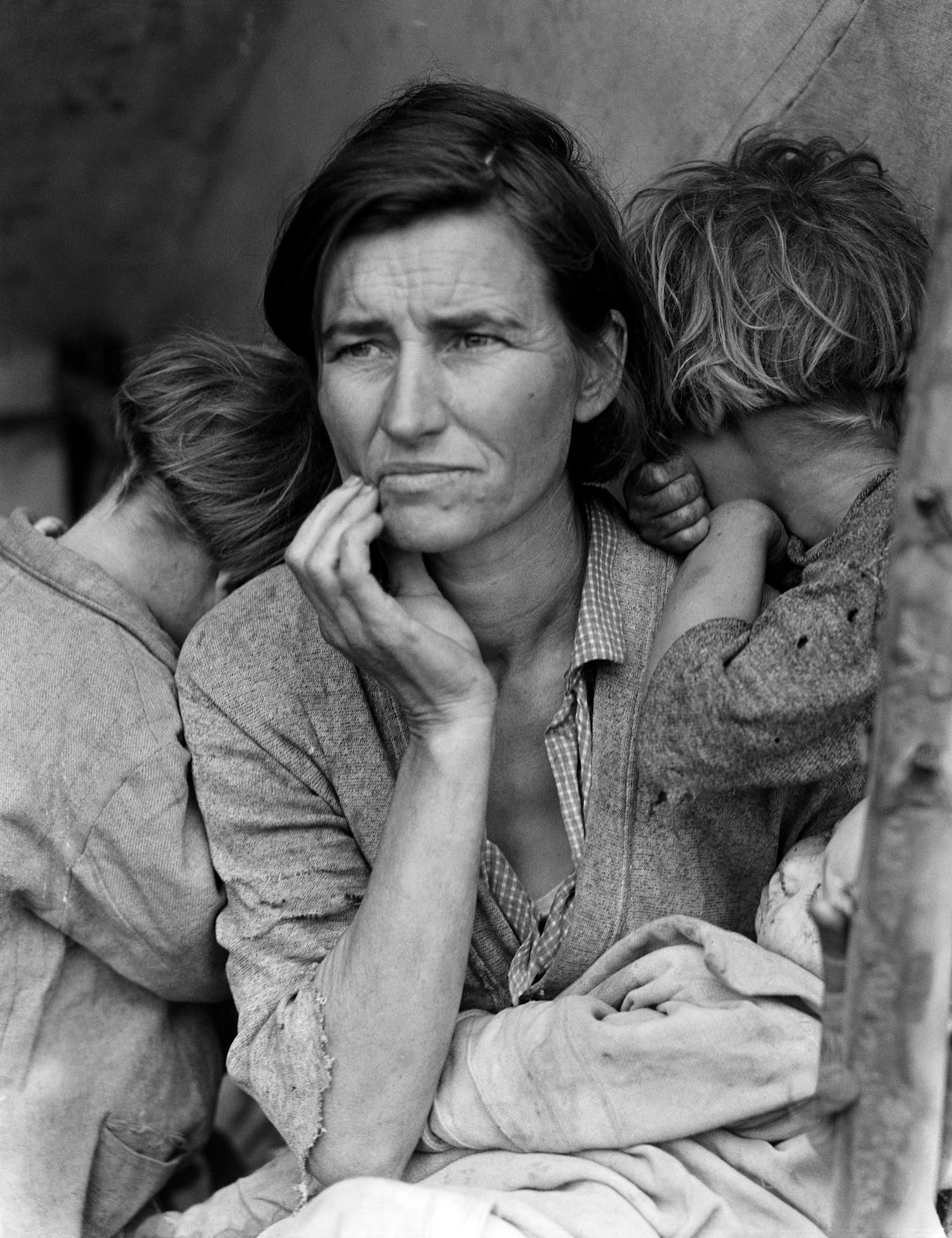

SMS Szent Istvan by K.u.k. Kriegsmarine personnel via Wikimedia Commons.

All the technological changes in Western Civilization led to more than just drastic changes in work, production, and calls for reform. They also impacted the way in which people killed each other. Until 1914, the American Civil War had stood out as the greatest self-inflicted tragedy in western civilization, with more than half a million people killed. World War I would eclipse this conflict twenty-eight times over.

Twenty years later World War II would multiply even this tragedy over four-fold. Mechanized warfare would shock the world like nothing else before or since.

The spark came in Serbia when the heir to the Austrian throne was murdered by a Serbian anarchist in late June of 1914. Determined to punish the Serbians, Austria began planning a response. Russia, with its close ethnic ties to Serbia, warned Austria against a harsh response and began mobilizing its troops on the German border in case the German's should strike Russia in Austria's defense. The Germans interpreted this build up as an act of aggression and invaded Russia. Another war was on. This time it would engulf the entire world.

Video (00:06:19) World War One Begins (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36216&loid=407078)

Video (00:02:00) The Presidents Wilson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43179&loid=449571)

To the American public, the outbreak of war in Europe came as a shock. At first the encounter seemed remote, but its economic and political effects were swift and deep. By 1915 U.S. industry, which had been mildly depressed, was prospering again with munitions orders from the Western Allies. Both sides used propaganda to arouse the public passions of Americans — a third of whom were either foreign-born or had one or two foreign-born parents. Moreover, Britain and Germany both acted against U.S. shipping on the high seas, bringing sharp protests from President Woodrow Wilson.

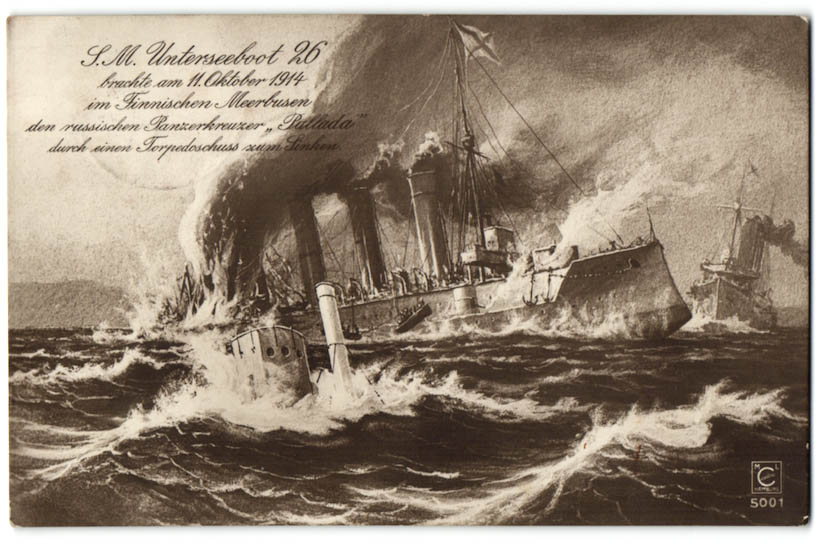

America’s neutrality was made difficult due its “tossed salad” mixture of ethnicities and the high-handed actions of the Germans both on the high seas and in neutral countries. With the allied powers, Americans shared a common language and culture. However, German and Irish-Americans were a sizable portion of the U.S. population. German Americans were naturally drawn toward their homeland, while the Irish supported anyone who opposed the British. Nonetheless, neutrality is what President Wilson proclaimed and he had no intention of joining hostilities. While the German military machine dominated on land, the British navy ruled the seas. As Americans claimed the right to ship to and from both sides, geography dictated that the only meaningful destination was Great Britain as British ships blockaded German ports. The effective result was that, Americans actively supported the British and became a real threat to the Axis cause. With the German invasion of Neutral Belgium and submarine attacks against American shipping, public opinion shifted quickly toward the Allies. When the passenger ship Lusitania was sunk in 1915, the Americans threatened direct intervention against the Germans.

Video (00:04:14) World War One Weapons (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36216&loid=407079)

Video (00:04:14) World War One Weapons (http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewVideo.aspx?xtid=36216&loid=407079)

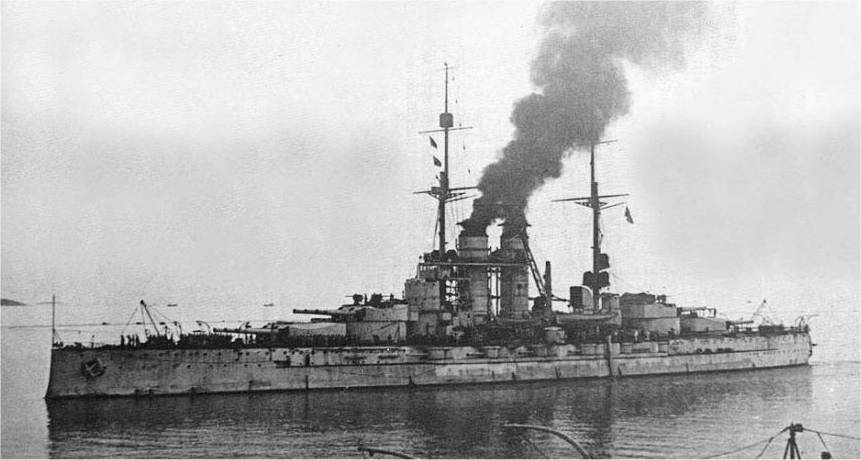

Britain stopped and searched American carriers, confiscating “contraband” bound for Germany. Germany employed its major naval weapon, the submarine, to sink shipping bound for Britain or France. President Wilson warned that the United States would not forsake its traditional right as a neutral to trade with belligerent nations. He also declared that the nation would hold Germany to “strict accountability” for the loss of American vessels or lives. After the Lusitania was sunk killing 1,198 people, 128 of them Americans, Wilson, reflecting American outrage, demanded an immediate halt to attacks on liners and merchant ships.

A crisis resulted in the German high command over whether to scale back on u-boat warfare or step up u-boat activity and risk American intervention. For the moment, the Germans backed down. Anxious to avoid war with the United States, Germany agreed to give warning to commercial vessels — even if they flew the enemy flag — before firing on them. But after two more attacks — the sinking of the British steamer Arabic in August 1915, and the torpedoing of the French liner Sussex in March 1916 — Wilson issued an ultimatum threatening to break diplomatic relations unless Germany abandoned submarine warfare. Germany agreed and refrained from further attacks through the end of the year.

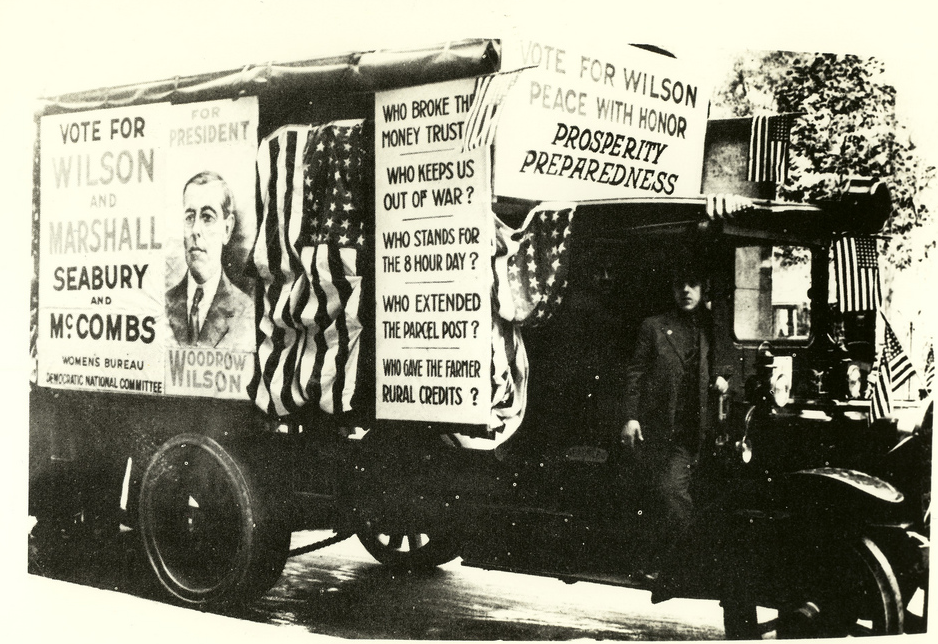

Wilson won reelection in 1916, partly on the slogan: “He kept us out of war.” Feeling he had a mandate to act as a peacemaker, he delivered a speech to the Senate, January 22, 1917, urging the warring nations to accept a “peace without victory.”

Video (0011:53) One Woman One Vote (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=44178&loid=448495)

UNITED STATES ENTERS WORLD WAR I

![American officers training in rifle, grenade, and bombing practice at the British Corps School, By UBC Library Digitization Centre [No restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3471)

American officers training in rifle, grenade, and bombing practice at the British Corps School, By UBC Library Digitization Centre [No restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons

Americans joined the allied effort in 1917 due to economics, the political future of Europe, a resurgence of U-boat warfare and yet another ill-timed telegram. President Wilson had won the election in 1916 largely on his promise to keep Americans out of the war. However, with public opinion clearly shifting toward the allies and with French and British debt to American creditors quickly building, Americans saw a stake in the war's outcome.

An allied loss would mean substantial unpaid debts and a decided shift away from democracy and toward a more autocratic Europe. As Americans built an army, President Wilson's world-wide popularity grew exponentially as the one who could rise above the slaughter and envision a new peace and a new world. In the first half of 1917, Russia, withdrew from the war, thereby freeing up all German divisions in the East to make a massive offensive in the West.

At nearly the same time, the German high command decided to risk American entry by declaring unrestricted submarine warfare, gambling that they could overrun Western Europe before Americans could make a meaningful contribution. This was probably enough to bring the Americans in, but a cable from Berlin to Mexico--the Zimmerman Telegram--was intercepted. In this telegram the Germans offered to give back to Mexico all the territory lost in the Mexican American war if they would side with the Axis and invade the U.S. from the South. The Americans declared war.

Russian Revolution

The reasons for Russian withdrawal were two-fold. First, Russians had been struggling under an inept monarch for decades and, when war came, faced a mechanized enemy while they themselves were on horseback using rusty, single-shot carbines. The Russians were weak and unprepared. Secondly, the Russian people were hungry, frustrated and ready to rebel. Initially, the revolution overthrew the tsar and established a teetering democracy which promised to continue the war effort.

Seizing the opportunity afforded by the poor performance of the Russian Army and horrid home conditions in Russia, Vladimir Lenin led the Bolsheviks into power and out of the war against Germany, thus freeing dozens of German units to concentrate on the western front. Marxist rhetoric had blamed the past several years of bloodshed on capitalist nations sending out workers to kill each other to support Capitalism. Vladimir Lenin seized upon this and called the workers of the world to stop killing each other and turn against Capitalism. Though this did not have the intended effect, the Great Depression—just a decade away—would appear to many as the failure of Capitalism and a justification of Lenin's brand of Marxism.

![Vladimir Lenin speaking to a crowd, published by Boni and Liveright, NY, 1921 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3472)

Vladimir Lenin speaking to a crowd, published by Boni and Liveright, NY, 1921 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Mobilization

With the Russian's out and the Americans in, Western Europe had gained a better equipped ally but now had to face a much stronger enemy as newly freed up German units arrived from the Russian front. In accordance with their Schlieffen plan the Germans launched a major offensive to bring Western Europe under their control before the Americans could gain their footing. The Americans stopped them at Belleau Wood, suffering 5,000 marine casualties. Over a half million Americans fought to recapture St. Mihiel and over a million fought in the Meuse-Argonne offensive which cracked Germany’s vaunted Hindenburg Line. The war then settled back into a stalemate in the trenches. Occasional raids back and forth netted little ground and much death as machine guns tore men to pieces on both sides. Men who had marched off to glory a few short years ago now questioned the sense of it all and wondered what they were fighting for.

Video (00:28:58) Americans at War (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36216&loid=407080)

Home Front

At home, Americans supported the war effort by giving up luxuries, volunteering, enacting wartime laws, cooperation between labor and industry and even through renaming traditional German foods. The “Captains of Industry” served in war industries for a dollar a year. War industries were organized under a new War Labor Board and cooperated with labor in board-sponsored arbitration of disputes. Women worked factory jobs while men were overseas (though men would reclaim those jobs upon their return) and black Americans engaged in one of the largest migrations out of the American South as they moved north to work in war industries (White men would also want these jobs upon their return). Americans engaged in meatless and wheatless days; the president grazed sheep on the White House law; celebrities peddled war bonds and children and the elderly knitted wool sweaters and socks for the soldiers.

![Charlie Chaplin stands on Douglas Fairbanks' shoulders during a Liberty bonds rally. They are at the foot of George Washington’s statue in front of the Sub-Treasury. By Underwood & Underwood (see lens.blogs.nytimes.com) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3474)

Charlie Chaplin stands on Douglas Fairbanks' shoulders during a Liberty bonds rally. They are at the foot of George Washington’s statue in front of the Sub-Treasury. By Underwood & Underwood (see lens.blogs.nytimes.com) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Patriotic sentiment swelled as the Committee on Public Information mass-produced Wilson's speeches and various war propaganda. The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 barred “seditious” materials from the post, allowed for deportations and forbade disloyal language. These would inspire the creation of the National (later the “American”) Civil Liberties Union in 1917 to defend those abused by these war-time acts. The renaming of the Frankfurter and Sauerkraut into the "Hot Dog" and "Liberty Cabbage" respectively, joined a ban on the teaching of German language at the more extreme limits of patriotism.

![Council of Four at the WWI Paris peace conference, May 27, 1919: (Left - Right) Prime Minister David Lloyd George (Great Britain) Premier Vittorio Orlando, Italy, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, President Woodrow Wilson. By Edward N. Jackson (US Army Signal Corps) (U.S. Signal Corps photo) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3475)

Council of Four at the WWI Paris peace conference, May 27, 1919: (Left - Right) Prime Minister David Lloyd George (Great Britain) Premier Vittorio Orlando, Italy, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, President Woodrow Wilson. By Edward N. Jackson (US Army Signal Corps) (U.S. Signal Corps photo) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Peace came largely as a result of successful American (primarily Wilsonian) propaganda. President Wilson had effectively, and to a large extent rightly, distanced himself and the nation from the causes of World War One. As a result, he found himself in a unique position to arbitrate the conflict even as a combatant. Wilson characterized the struggle as being waged not against the German people but against their autocratic government. President Wilson favored a “peace without victory” and the Committee for Public Information made sure his message reached all of Europe. Of particular importance to Wilson was point fourteen of his “Fourteen Point Plan” which would establish a “League of Nations” to ensure the future peace. As German hopes of victory faded, Wilson’s version of peace began to look attractive. The German army laid down their arms largely on the hopes and expectations derived from Wilson’s speeches.

His Fourteen Points, submitted to the Senate in January 1918, called for: abandonment of secret international agreements; freedom of the seas; free trade between nations; reductions in national armaments; an adjustment of colonial claims in the interests of the inhabitants affected; self-rule for subjugated European nationalities; and, most importantly, the establishment of an association of nations to afford “mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.”

In October 1918, the German government, facing certain defeat, appealed to Wilson to negotiate on the basis of the Fourteen Points. After a month of secret negotiations that gave Germany no firm guarantees, an armistice (technically a truce, but actually a surrender) was concluded on November 11.

Video (00:14:04) One Woman, One Vote (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=44178&loid=448496)

Video (00:04:32) Wilson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43179&loid=94098)

THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS

President Wilson had traveled to and resided in Europe during the winter of 1918-19 to oversee peace talks and was received enthusiastically by the European populace. The peace negotiated at Paris, however, was doomed to failure due to unyielding allied powers and Wilson's considerable diplomatic mistakes. Wilson's long absence from the United States with a partisan delegation, which included no high-ranking Republicans or senators (the very body which ratifies foreign treaties), meant that the opposition could, and did, build a case against the president's efforts even before the final agreement was inked in Europe. It was Wilson’s hope that the final treaty, drafted by the victors, would be even-handed, but the passion and material sacrifice of more than four years of war caused the European Allies to make severe demands.Great Britain, France and Italy's insistence on prewar border rearrangements, confiscation of German overseas colonies and huge reparations payments destroyed the number-one selling point for the Germans (peace without victory) and left them seething. Persuaded that his greatest hope for peace, a League of Nations, would never be realized unless he made concessions, Wilson compromised somewhat on the issues of self-determination, open diplomacy, and other specifics. He successfully resisted French demands for the entire Rhineland, and somewhat moderated that country’s insistence upon charging Germany the whole cost of the war. The final agreement (the Treaty of Versailles), however, provided for French occupation of the coal- and iron-rich Saar Basin, and a very heavy burden of reparations upon Germany.

![Woodrow Wilson. By Underwood & Underwood [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3476)

Woodrow Wilson. By Underwood & Underwood [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The last nail in the treaty's coffin came when Wilson returned to the United States and took his treaty directly to the people, bypassing Congress altogether. When the Senate rejected the treaty in 1920, Europe was left with a treaty and a League of Nations which lacked the instigating member.

In the end, there was little left of Wilson’s proposals for a generous and lasting peace but the League of Nations itself, which he had made an integral part of the treaty. Displaying poor judgment, however, the president had failed to involve leading Republicans in the treaty negotiations. Returning with a partisan document, he then refused to make concessions necessary to satisfy Republican concerns about protecting American sovereignty.

With the treaty stalled in a Senate committee, Wilson began a national tour to appeal for support. On September 25, 1919, physically ravaged by the rigors of peacemaking and the pressures of the wartime presidency, he suffered a crippling stroke. Critically ill for weeks, he never fully recovered. In two separate votes — November 1919 and March 1920 — the Senate once again rejected the Versailles Treaty and with it the League of Nations.

The League of Nations would never be capable of maintaining world order. Wilson’s defeat showed that the American people were not yet ready to play a commanding role in world affairs. His utopian vision had briefly inspired the nation, but its collision with reality quickly led to widespread disillusion with world affairs.

The Final Costs

The final tally saw 50,000 Americans killed in battle; 60,000 killed from disease (mostly influenza) and 15,000,000 deaths worldwide. There were arguably as many deaths from this one war, fought in the name of national pride and influence, than from all combined wars ever fought in the name of God (or any other scapegoat for that matter). Americans especially took notice of the seemingly “god-less” turn of events sweeping western civilization and sought a return to isolationism and introspection.The growing belief in "Progress,” or “Modernism,” as an unstoppable force, had self-destructed in the fields and trenches of France.

In its place came the much more pessimistic worldview known as "Postmodernism." Rather than viewing the airplane, for example, as evidence of progress, the Postmodernist saw its capacity to drop bombs and inflict suffering. One of the primary postmodern claims is that because we cannot know any Absolute Truth claims for certain, there is therefore no Absolute Truth. This, of course, is an Absolute Truth statement. More recent thinkers are conceding that many truths may indeed be absolute even if we cannot understand them in an absolute sense.

POSTWAR UNREST

While America and other western nations retreated from the First World War to lick their wounds and avoid international entanglements, the sounds of tickertape replaced that of mortars, and an economic boom—centered on the United States—swept the globe. With the American and European belief in "Progress" now in smoking ruins, Americans, tired of war, turned their attentions inward to the affluence that a wartime economy had brought and toward internal enemies both real and imagined. Americans spent and consumed like never before and the Stock Market climbed to unprecedented heights. The Automobile revolutionized transportation, and changed the physical and social landscape of America.

Thus we are introduced to the roaring twenties with its drastic cultural shifts, risqué new styles, changing expectations and scandals. All of this led relentlessly toward the economic crash of 1929 as Americans failed to understand that a consumer economy required constant consumption, not just investment, to succeed. The brief period of post-war uncertainty in industry and society quickly gave way to economic euphoria just as financial collapse, depression and a second world war more calamitous than the first appeared on the horizon.

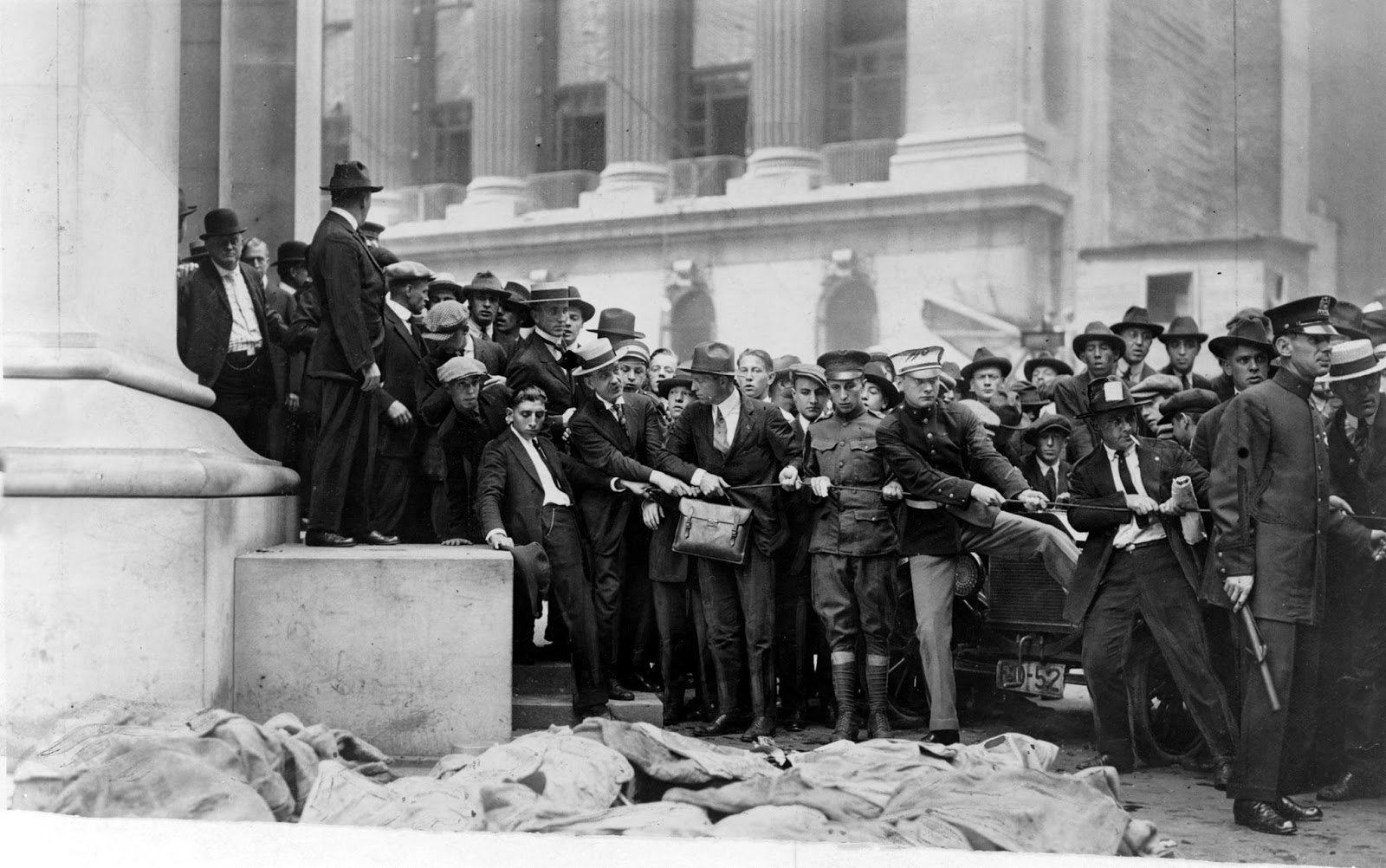

The transition from war to peace proved tumultuous. The postwar economic boom coexisted with rapid increases in consumer prices. Labor unions that had refrained from striking during the war engaged in several major job actions. During the summer of 1919, several race riots occurred, reflecting apprehension over the emergence of a “New Negro” who had seen military service or gone north to work in the war industry.

![African American being stoned by whites during 1919 Chicago race riot. By Chicago Commission on Race Relations. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3477)

African American being stoned by whites during 1919 Chicago race riot. By Chicago Commission on Race Relations. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Uncertainty

While American wartime industry resulted in unprecedented prosperity, there was a brief period of uncertainty as industry demobilized and jobs were lost at war’s end. Additionally, American farmers who had benefited most from the war were no longer needed to feed Europe and the American army. Riots and strikes returned to Industry which had lost its war-time demand for production. However, with European factories also in smoking ruins, Americans quickly found themselves without meaningful competition and, once retooled, soon dominated the consumer markets of most of the world. Adding to this brief period of uncertainty was the first Red Scare.

![American troops in Vladivostok parading before the building occupied by the staff of the Czecho-Slovaks. Japanese marines are standing at attention as they march by. Siberia, August 1918. By Underwood & Underwood (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3478)

American troops in Vladivostok parading before the building occupied by the staff of the Czecho-Slovaks. Japanese marines are standing at attention as they march by. Siberia, August 1918. By Underwood & Underwood (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The fear of Communist ideology and its prediction of worldwide revolution and class warfare was particularly frightening at the end of such a calamity as World War One. At war’s end in 1918, the allies (including the United States) had sent expeditionary forces into Russia to support the recently ousted democratic regime against the newly empowered Bolsheviks. After two years, the only thing produced was ill will toward western powers and reason to believe that the Communists might, in retaliation, try to infiltrate and overthrow western nations. After a series of mail bombs to high ranking American Politicians, Americans were convinced of such a plot and the Communist Party of the United States was significantly weakened by a series of questionably legal raids by Attorney General Palmer and J. Edgar Hoover. Reaction to these events merged with a widespread national fear of a new international revolutionary movement. After their seizure of power in 1917, the Bolsheviks attempted revolutions in Germany and Hungary. By 1919, it seemed they had come to America. Excited by the Bolshevik example, large numbers of militants split from the Socialist Party to found what would become the Communist Party of the United States. In April 1919, the postal service intercepted nearly 40 bombs addressed to prominent citizens. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s residence in Washington was bombed. Palmer,in turn, authorized federal roundups of radicals and deported many who were not citizens. Strikes were often blamed on radicals and depicted as the opening shots of a revolution.

Palmer’s dire warnings fueled a “Red Scare” that subsided by mid- 1920. Even a murderous bombing in Wall Street in September failed to reawaken it. From 1919 on, however, a current of militant hostility toward revolutionary communism would simmer not far beneath the surface of American life.

THE BOOMING 1920s

Wilson, distracted by the war, then laid low by his stroke, had mishandled almost every post-war issue. The booming economy began to contract in mid-1920. The Republican candidates for president and vice president, Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge, easily defeated their Democratic opponents, James M. Cox and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Following ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, women voted in a presidential election for the first time.

Video (00:07:41) One Woman, One Vote (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=44178&loid=448498)

Video (00:01:55) The Presidents:Harding (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43179&loid=94099)

![“Do you know how to kiss a girl?” Advertisement by Common Sense Gum Company [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3480)

“Do you know how to kiss a girl?” Advertisement by Common Sense Gum Company [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The economic health of a consumer society requires that the average citizen be both able and willing to spend. While Henry Ford and other industrialists worked on the "able" part of the equation, the growing industry of advertising worked on the "willing" part. Advertising became a huge industry in the 1920s as industrialists turned to advertising agencies to convince Americans of a need for their products. These agencies used fear, sex, guilt, prestige, vanity and every other conceivable human motivator to sell products.

Henry Ford's perfecting of the assembly line was a model for other industries and consumer goods began flowing out of American factories at an unheard of pace. In order to obtain consumers to keep up with production, Ford, followed by other industrialists, brought production prices down and elevated wages so his workers could buy his product. This was the birth of the first real consumer society.

The first two years of Harding’s administration saw a continuance of the economic recession that had begun under Wilson. By 1923, however, prosperity had returned. For the next six years the country enjoyed the strongest economy in its history, at least in urban areas. Governmental economic policy during the 1920s was eminently conservative. It was based upon the belief that if government fostered private business, benefits would radiate out to most of the rest of the population.

Accordingly, the Republicans tried to create the most favorable conditions for U.S. industry. The Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922 and the Hawley-Smoot Tariff of 1930 brought American trade barriers to new heights, guaranteeing U.S. manufacturers in one field after another a monopoly of the domestic market, but blocking a healthy trade with Europe that would have reinvigorated the international economy. Occurring at the beginning of the Great Depression, Hawley- Smoot triggered retaliation from other manufacturing nations and contributed greatly to a collapsing cycle of world trade that would intensify world economic misery.

The federal government also started a program of tax cuts, reflecting Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon’s belief that high taxes on individual incomes and corporations discouraged investment in new industrial enterprises. Congress, in laws passed between 1921 and 1929, responded favorably to his proposals.

Video (00:04:88) The Presidents:Coolidge (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43179&loid=94101)

“The chief business of the American people is business,” declared Calvin Coolidge, the Vermont-born vice president who succeeded to the presidency in 1923 after Harding’s death, and was elected in his own right in 1924. Coolidge hewed to the conservative economic policies of the Republican Party, but he was a much abler administrator than the hapless Harding, whose administration had been mired in charges of corruption in the months before his death.

![County agent Bennion and farmer C. L. May discuss the potato prospects of the community in Umatilla County, Westin, Oregon on July 21, 1925. Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration. By U.S. Department of Agriculture [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3481)

County agent Bennion and farmer C. L. May discuss the potato prospects of the community in Umatilla County, Westin, Oregon on July 21, 1925. Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration. By U.S. Department of Agriculture [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr

Throughout the 1920s, private business received substantial encouragement, including construction loans, profitable mail-carrying contracts, and other indirect subsidies. The Transportation Act of 1920, for example, had already restored to private management the nation’s railways, which had been under government control during the war. The Merchant Marine, which had been owned and largely operated by the government, was sold to private operators. Republican policies in agriculture, however, faced mounting criticism, for farmers shared least in the prosperity of the 1920s. The period since 1900 had been one of rising farm prices. The unprecedented wartime demand for U.S. farm products had provided a strong stimulus to expansion. But by the close of 1920, with the abrupt end of wartime demand, the commercial agriculture of staple crops such as wheat and corn fell into sharp decline. Many factors accounted for the depression in American agriculture, but foremost was the loss of foreign markets. This was partly in reaction to American tariff policy, but also because excess farm production was a worldwide phenomenon. When the Great Depression struck in the 1930s, it devastated an already fragile farm economy.

The distress of agriculture aside, the Twenties brought the best life ever to most Americans. It was the decade in which the ordinary family purchased its first automobile, obtained refrigerators and vacuum cleaners, listened to the radio for entertainment, and went regularly to motion pictures. Prosperity was real and broadly distributed. The Republicans profited politically, as a result, by claiming credit for it.

The Automobile

The pace of change which had quickened during the Civil War years became dizzying during the early 20th century. Though it had a difficult time getting established in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the gasoline powered automobile would change the lives of everyone on the planet and none more so than Americans. Some of the advantages were obvious. Rather than traveling to a train station to make a long distance trip, the depot was now literally at one's house and the train station could be bypassed entirely.

Video (00:01:10) Highland Park Generator(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/x9F3Wij4)

This new mobility allowed for larger commutes to work, hence, larger cities. As the range of human mobility increased, the traditional extended family disintegrated further and spread out over, first the city, then the county, state and nation.

In the same way that Railroads had served as industry multipliers in the late 1800s, automobiles spawned multiple industries in the 1920s. While the Railroads had encouraged tourism and hotels “at” various destinations, automobiles encouraged tourism and “motels” (motor hotels) “enroute” to destinations. The oil industry which had been large before the 1920s became huge as gasoline and tires (both refined from oil) became necessities of a consumer culture. Service stations garages and motels dotted the landscape and public demand for more and better highways (asphalt is also a petroleum product) further changed the landscape of America. This one American obsession, more than most, would define and shape both American culture at home and American relations in the Middle East in future years.

Cultural Homogenization

A shift from manufacturing to consumer goods, increased efficiency, decreasing prices and technological advancements all added up to cultural homogenization for Americans. As Ford produced millions of Model T’s, the chances of seeing the same car of the same color increased drastically. Radios were turned out by the millions in the 1920s. As large radio corporations put out more powerful signals than local stations, Americans became familiar with the same characters, products and personalities via radio. Tens of thousands of movie theaters made Hollywood personalities and faces familiar to most Americans during the 1920s as well.

TENSIONS OVER IMMIGRATION

During the 1920s, the United States sharply restricted foreign immigration for the first time in its history. Large influxes of foreigners long had created a certain amount of social tension, but most had been of Northern European stock and, if not quickly assimilated, at least possessed a certain commonality with most Americans. By the end of the 19th century, however, the flow was predominantly from southern and Eastern Europe. According to the census of 1900, the population of the United States was just over 76 million. Over the next 15 years, more than 15 million immigrants entered the country.

Around two-thirds of the inflow consisted of “newer” nationalities and ethnic groups — Russian Jews, Poles, Slavic peoples, Greeks, southern Italians. They were non-Protestant, non-“Nordic,” and, many Americans feared, non-assimilable. They did hard, often dangerous, low-pay work — but were accused of driving down the wages of native-born Americans. Settling in squalid urban ethnic enclaves, the new immigrants were seen as maintaining Old World customs, getting along with very little English, and supporting unsavory political machines that catered to their needs. Nativists wanted to send them back to Europe; social workers wanted to Americanize them. Both agreed that they were a threat to American identity.

Halted by World War I, mass immigration resumed in 1919, but quickly ran into determined opposition from groups as varied as the American Federation of Labor and the reorganized Ku Klux Klan. Millions of old-stock Americans who belonged to neither organization accepted commonly held assumptions about the inferiority of non-Nordics and backed restrictions. Of course, there were also practical arguments in favor of a maturing nation putting some limits on new arrivals.

In 1921, Congress passed a sharply restrictive emergency immigration act. It was supplanted in 1924 by the Johnson-Reed National Origins Act, which established an immigration quota for each nationality. Those quotas were pointedly based on the census of 1890, a year in which the newer immigration had not yet left its mark. Bitterly resented by southern and Eastern European ethnic groups, the new law reduced immigration to a trickle. After 1929, the economic impact of the Great Depression would reduce the trickle to a reverse flow — until refugees from European fascism would begin to press for admission to the country.

CLASH OF CULTURES

Billy Sunday. Author Unknown, via Wikimedia Commons

Some Americans expressed their discontent with the character of modern life in the 1920s by focusing on family and religion, as an increasingly urban, secular society came into conflict with older rural traditions. Fundamentalist preachers such as Billy Sunday provided an outlet for many who yearned for a return to a simpler past.

Perhaps the most dramatic demonstration of this yearning was the religious fundamentalist crusade that pitted Biblical texts against the Darwinian theory of biological evolution. In the 1920s, bills to prohibit the teaching of evolution began appearing in Midwestern and Southern state legislatures. Leading this crusade was the aging William Jennings Bryan, long a spokesman for the values of the countryside as well as a progressive politician. Bryan skillfully reconciled his anti-evolutionary activism with his earlier economic radicalism, declaring that evolution “by denying the need or possibility of spiritual regeneration, discourages all reforms.”

![Anti-Evolution League, at the Scopes Trial, Dayton Tennessee from Literary Digest July 25, 1925. By Mike Licht [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3482)

Anti-Evolution League, at the Scopes Trial, Dayton Tennessee from Literary Digest July 25, 1925. By Mike Licht [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The issue came to a head in 1925, when a young high school teacher, John Scopes, was prosecuted for violating a Tennessee law that forbade the teaching of evolution in the public schools. The case became a national spectacle, drawing intense news coverage. The American Civil Liberties Union, seeking a chance to bring the issue to national attention, approached some Dayton businessmen who were eager to bring more attention to their town. They then contacted Scopes who agreed to teach evolution in his class. Clarence Darrow was then retained to defend Scopes.

Bryan wrangled an appointment as special prosecutor, then foolishly allowed Darrow to call him as a hostile witness. Bryan’s confused defense of Biblical passages as scientific rather than religious truth drew widespread criticism. Scopes, nearly forgotten in the fuss, was convicted, but his fine was reversed on a technicality. Bryan died shortly after the trial ended. The state wisely declined to retry Scopes. Urban sophisticates ridiculed Fundamentalism, but Fundamentalism continued to be a powerful force in rural, small-town America.

Another example of a powerful clash of cultures — one with far greater national consequences — was Prohibition. In 1919, after almost a century of agitation, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was enacted, prohibiting the manufacture, sale, or transportation of alcoholic beverages. Intended to eliminate the saloon and the drunkard from American society, Prohibition created thousands of illegal drinking places called “speakeasies,” made intoxication fashionable, and created a new form of criminal activity — the transportation of illegal liquor, or “bootlegging.” Widely observed in rural America, openly evaded in urban America, Prohibition was an emotional issue in the prosperous Twenties. When the Depression hit, it seemed increasingly irrelevant. The 18th Amendment would be repealed in 1933.

Fundamentalism and Prohibition were aspects of a larger reaction to a modernist social and intellectual revolution most visible in changing manners and morals that caused the decade to be called the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties, or the era of “flaming youth.” World War I had overturned the Victorian social and moral order. Mass prosperity enabled an open and hedonistic lifestyle for the young middle classes.

The leading intellectuals were supportive. H.L. Mencken, the decade’s most important social critic, was unsparing in denouncing sham and venality in American life. He usually found these qualities in rural areas and among businessmen. His counterparts of the progressive movement had believed in “the people” and sought to extend democracy. Mencken, an elitist and admirer of Nietzsche, bluntly called democratic man a boob and characterized the American middle class as the “booboisie.”

Novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald captured the energy, turmoil, and disillusion of the decade in such works as The Beautiful and the Damned (1922) and The Great Gatsby (1925). Sinclair Lewis, the first American to win a Nobel Prize for literature, satirized mainstream America in Main Street (1920) and Babbitt (1922). Ernest Hemingway vividly portrayed the malaise wrought by the war in The Sun Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1929). Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and many other writers dramatized their alienation from America by spending much of the decade in Paris.

African-American culture flowered Between 1910 and 1930, huge numbers of African Americans moved from the South to the North in search of jobs and personal freedom. Most settled in urban areas, especially New York City’s Harlem, Detroit, and Chicago. In 1910 W.E.B. DuBois and other intellectuals had founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which helped African Americans gain a national voice that would grow in importance with the passing years.

An African-American literary and artistic movement, called the “Harlem Renaissance,” emerged. Like the “Lost Generation,” its writers, such as the poets Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen, rejected middle-class values and conventional literary forms, even as they addressed the realities of African-American experience. African- American musicians — Duke Ellington, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong — first made jazz a staple of American culture in the 1920s.

The 1920s were nothing if they were not about “change.” Even the sameness of cultural homogenization was a change from the individualism Americans had been used to. Hem lines ascended and necklines descended as the brash, new “flapper” experimented with smoking, dancing, dating and working in a culture that had turned the corner from rural to urban. Writers, alienated by mechanized warfare and modern society, produced criticisms of war like “The Waste Land” and of society like “The Great Gatsby.” Perhaps the greatest potential change and greatest disappointment came in the form of suffrage. President Wilson had adopted the issue during World War One under pressure from Alice Paul, a radical suffragette and constant nuisance at the front of the White House. Half the suffragettes had quieted their demands and worked toward both suffrage and victory due to the war; Alice Paul, however, chained herself to the White House Fence. The great disappointment came when voting patterns changed almost imperceptibly with the adoption of the 19th amendment. The hoped-for reforms and the feared disenfranchisement of men never materialized.

THE CRASH

In October 1929, the Stock Market crashed as a result of under consumption, over speculation and European caution. Americans, sensing money to be made in the Stock Market, had largely stopped buying the products companies made, in favor of buying company stock instead. Often they did so on margin which meant they would put down ten percent, yet be responsible for the entire amount. The balance would be covered by a bank loan. The expectation was that the investor would profit on the entire amount of stock, sell it, pay off the loan and pocket the difference. This massive infusion of funds into company stocks made the stocks soar. Companies put the profit into making more product at a time when Americans were buying company stock instead of company product. This effectively cancelled a company’s reason for being and put Americans who took out these marginal loans (and the banks that gave them) onto shaky financial ground.

Numerous charlatans caught on to this phenomenon and pooled together to run up the stock of various companies. The sudden rise of the company’s stock would lure in investors. Those running the scheme would then dump their shares at the inflated price. The precipitating event for the crash, however, came in late 1929, when European investors, sensing a financial house of cards, started pulling out of their American investments. This created a need for cash to pay them off.

In October, 1929 the banks' and brokerage firms' need for cash to pay off withdrawing Europeans, caused them to call in loans they’d made to American investors. These investors then sold their marginal stock to pay off their loans. As stock was sold it quickly lost its per-share value and the market spun out of control. In the space of a few weeks, the American economy lost the equivalent of twice that year’s national debt.

Video (00:07:12) Crash (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36219&loid=408815)

The breadth and width of the Depression was vast, destroying incomes domestically and creating the conditions for foreign political changes with far reaching consequences. In the first three years of the Depression unemployment rose to 25%, the national income was cut in half, and 5,000 banks closed their doors. The assets of these banks had been tied up in marginal stock loans and mortgages that could no longer be paid by workers who were no longer working at companies which had lost their reason for being. Now that America was a predominantly urban society, great masses of people were unable to feed themselves as most were no longer on farms. One quarter of the state of Mississippi went to auction on a single day. More than 80% of rural schools in Alabama were closed. European debtors defaulted.

With American credit no longer available to Germany, reparations payments to the allies were defaulted on in 1931 and the German economy collapsed. Two years later, Adolph Hitler would come to power by playing on German anger at the dismal economy inherited from the lop-sided peace treaty of World War One. That economy, bad as it was, utterly collapsed in the Depression and the German sense of betrayal ran deep.

Video (00:03:12) The Presidents: Hoover (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43179&loid=94102)

The presidential campaign of 1932 was chiefly a debate over the causes and possible remedies of the Great Depression. President Herbert Hoover, unlucky in entering the White House only eight months before the stock market crash, had tried harder than any other president before him to deal with economic hard times. He had attempted to organize business, had sped up public works schedules, established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to support businesses and financial institutions, and had secured from a reluctant Congress an agency to underwrite home mortgages. Nonetheless, his efforts had little impact, and he was a picture of defeat.

His Democratic opponent, Franklin D. Roosevelt, already popular as the governor of New York during the developing crisis, radiated infectious optimism. Prepared to use the federal government’s authority for even bolder experimental remedies, he scored a smashing victory — receiving 22,800,000 popular votes to Hoover’s 15,700,000. The United States was about to enter a new era of economic and political change.

Video (00:04:24) FDR (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43179&loid=448499)