Chapter 18 Postwar America

![Taken from the pamphlet television-promise. (306-PS-58-9015. [Public domain] via National Archives. http://www.archives.gov](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3599)

Taken from the pamphlet television-promise. (306-PS-58-9015. [Public domain] via National Archives. http://www.archives.gov

Total Video (00:26:86)

“We must build a new world, a far better world — one in which the eternal dignity of manis respected.” President Harry S. Truman, 1945

A COLD ERA

The era of the Cold War is one of the longest epochs of American history. It encompassed the end of World War II, several American wars in Southeast Asia, an arms build up, and an American social revolution. Difficulties during World War II would create a genuine sense of mistrust between the two future superpowers—The United States and Soviet Union. Conflicts in Korea and Vietnam would solidify each nation’s mistrust and lead to massive stockpiling of nuclear weapons on both sides. When the United States was challenged by its own youth in the 1960s and 1970s, the Soviets gleefully, but not realistically, hoped for a collapse of the U.S. system. Instead, the nation made long-overdue legal changes to the status of Black Americans, addressed some of the concerns of American youth, then followed up with a turn to the right ideologically.

CONSENSUS AND CHANGE

The United States dominated global affairs in the years immediately after World War II. Victorious in that great struggle, its homeland undamaged from the ravages of war, the nation was confident of its mission at home and abroad. U.S. leaders wanted to maintain the democratic structure they had defended at tremendous cost and to share the benefits of prosperity as widely as possible. For them, as for publisher Henry Luce of Time magazine, this was the “American Century.”

For 20 years most Americans remained sure of this confident approach. They accepted the need for a strong stance against the Soviet Union in the Cold War that unfolded after 1945. They endorsed the growth of government authority and accepted the outlines of the rudimentary welfare state first formulated during the New Deal. They enjoyed a postwar prosperity that created new levels of affluence.

But gradually some began to question dominant assumptions. Challenges on a variety of fronts shattered the consensus. In the 1950s, African Americans launched a crusade, joined later by other minority groups and women, for a larger share of the American dream. In the 1960s, politically active students protested the nation’s role abroad, particularly in the corrosive war in Vietnam. A youth counterculture emerged to challenge the status quo. Americans from many walks of life sought to establish a new social and political equilibrium.

PRE-COLD WAR BEGINNINGS

To understand the beginnings of the Cold War we must step briefly back into the nineteenth century and also consider wartime difficulties. When Karl Marx introduced Communist ideology in the mid-1800s, he did not claim that bloody revolutions “should” overthrow Capitalist governments, he predicted that they “would” overthrow Capitalist governments. Having (in his view) reduced history to “science,” he simply made a “scientific” prediction. Indeed, Marx believed any premature, manufactured revolution was bound to fail. By the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Vladimir Lenin had grown impatient and created his own version of “Socialism in one Country.”

Given the deplorable conditions under Russia’s tsar at the time, it’s not surprising that he was able to inspire and lead his Bolshevik’s to power. In Lenin’s view, bloody revolutions “should” throw off Capitalist chains and usher in Communism --one country at a time. So, even before World War II, capitalist democracies the world over were uncomfortable with the new “soviet” Russia. Early in the war, the Soviets were quickly demonized in the West when they threw in their lot with Hitler and divided Poland. Once Hitler turned on the Soviets, the Allies suddenly had an awkward alliance with a nation whose political goal was the destruction of western capitalist, democracies—them. This alliance would not last beyond the war and everyone knew it. Further complicating matters was Stalin’s dogged insistence on a second front. The more the Americans and British delayed opening that front, the more Stalin suspected them of encouraging the destruction of the soviet system, and the more determined he became to get something out of the war for Russia.

COLD WAR AIMS

At the war’s end, antagonisms surfaced again. The United States hoped to share with other countries its conception of liberty, equality, and democracy. It sought also to learn from the perceived mistakes of the post-WWI era, when American political disengagement and economic protectionism were thought to have contributed to the rise of dictatorships in Europe and elsewhere. Faced again with a postwar world of civil wars and disintegrating empires, the nation hoped to provide the stability to make peaceful reconstruction possible. Recalling the specter of the Great Depression (1929-40), America now advocated open trade for two reasons: to create markets for American agricultural and industrial products, and to ensure the ability of Western European nations to export as a means of rebuilding their economies. Reduced trade barriers, American policy makers believed, would promote economic growth at home and abroad, bolstering U.S. friends and allies in the process.

The Soviet Union had its own agenda. The Russian historical tradition of centralized, autocratic government contrasted with the American emphasis on democracy. Marxist-Leninist ideology had been downplayed during the war but still guided Soviet policy. Devastated by the struggle in which 20 million Soviet citizens had died, the Soviet Union was intent on rebuilding and on protecting itself from another such terrible conflict. The Soviets were particularly concerned about another invasion of their territory from the west. Having repelled Hitler’s thrust, they were determined to preclude another such attack. They demanded “defensible” borders and “friendly” regimes in Eastern Europe and seemingly equated both with the spread of Communism, regardless of the wishes of native populations. However, the United States had declared that one of its war aims was the restoration of independence and self-government to Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the other countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

Video (00:06:03) Truman (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=449873)

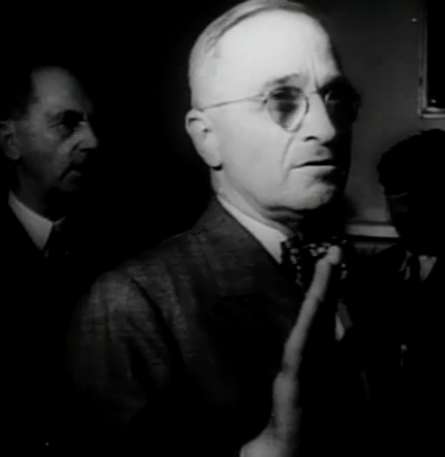

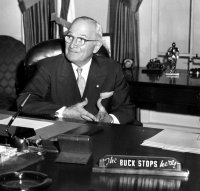

HARRY TRUMAN’S LEADERSHIP

The nation’s new chief executive, Harry S. Truman, succeeded Franklin D. Roosevelt as president before the end of the war. An unpretentious man who had previously served as Democratic senator from Missouri, then as vice president, Truman initially felt ill-prepared to govern. Roosevelt had not discussed complex postwar issues with him, and he had little experience in international affairs. “I’m not big enough for this job,” he told a former colleague.

Still, Truman responded quickly to new challenges. Sometimes impulsive on small matters, he proved willing to make hard and carefully considered decisions on large ones. A small sign on his White House desk declared, “The Buck Stops Here.” His judgments about how to respond to the Soviet Union ultimately determined the shape of the early Cold War.

Video (00:03:28) White House (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/o5S8GbBg)

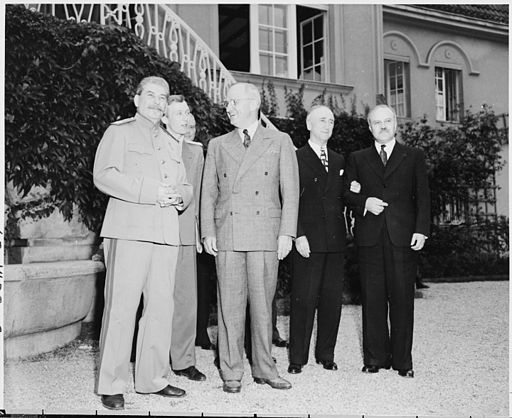

THE COLD WAR TAKES SHAPE

The Cold War developed as differences about the shape of the postwar world created suspicion and distrust between the United States and the Soviet Union. The first —and most difficult— test case was Poland, the eastern half of which had been invaded and occupied by the USSR in 1939. Moscow demanded a government subject to Soviet influence; Washington wanted a more independent, representative government following the Western model. The Yalta Conference of February 1945 had produced an agreement on Eastern Europe open to different interpretations. It included a promise of “free and unfettered” elections.

Meeting with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov less than two weeks after becoming president, Truman stood firm on Polish self-determination, lecturing the Soviet diplomat about the need to implement the Yalta accords. When Molotov protested, “I have never been talked to like that in my life,” Truman retorted, “Carry out your agreements and you won’t get talked to like that.” Relations deteriorated from that point onward.

![By Mosedschurte (en.wiki) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3600)

By Mosedschurte (en.wiki) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons

During the closing months of World War II, Soviet military forces occupied all of Central and Eastern Europe. Moscow used its military power to support the efforts of the Communist parties in Eastern Europe and crush the democratic parties. Communists took over one nation after another. The process concluded with a shocking coup d’etat in Czechoslovakia in 1948.

The “Iron Curtain”

Public statements defined the beginning of the Cold War. In 1946 Stalin declared that international peace was impossible “under the present capitalist development of the world economy.” Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered a dramatic speech in Fulton, Missouri, with Truman sitting on the platform. “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,” Churchill said, “an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.” Britain and the United States, he declared, had to work together to counter the Soviet threat.

CONTAINMENT

Containment of the Soviet Union became American policy in the postwar years. George Kennan, a top official at the U.S. embassy in Moscow, defined the new approach in the Long Telegram he sent to the State Department in 1946. He extended his analysis in an article under the signature “X” in the prestigious journal Foreign Affairs. Pointing to Russia’s traditional sense of insecurity, Kennan argued that the Soviet Union would not soften its stance under any circumstances. Moscow, he wrote, was “committed fanatically to the belief that with the United States there can be no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted.” Moscow’s pressure to expand its power had to be stopped through “firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies. ... ”

Early Containment

The first significant application of the containment doctrine came in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean. In early 1946, the United States demanded, and obtained, a full Soviet withdrawal from Iran, the northern half of which it had occupied during the war. That summer, the United States pointedly supported Turkey against Soviet demands for control of the Turkish straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. In early 1947, American policy crystallized when Britain told the United States that it could no longer afford to support the government of Greece against a strong Communist insurgency.

A moment of optimism was quickly replaced by diplomatic realities in 1946 and 1947 as Americans realized that they alone could contain the Soviet threat. The brief glimmer of hope emerged when, in 1946, the United States offered its nuclear stockpile to the U.N. in return for assurances from other nations, not to pursue nuclear weaponry. The Soviets rejected this offer as it would not allow them to “catch up” to the U.S.. The Soviets did hold elections in Eastern Europe, as promised--after coercing all opposition into compliance or out of existence. Then, the most influential two statements of the Cold War, penned by George F. Kennan, appeared in 1946 and 1947 respectively. Kennan, a former diplomat to Moscow, argued that Soviet expansion must be stopped. The Soviets must be “contained,” he argued, by meeting them with equal and opposite resistance every place they reached for more territory. Moreover, he claimed that the United States was the only power which could do so. “Containment” would become the official policy and driving force of United States foreign dealings for forty years.

Also that year, the National Security Act was passed. This act put the entire military under one head (the Secretary of Defense) and established the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to gather foreign intelligence. In a move that would bring ceaseless crisis to the Middle East, President Truman recognized the new state of Israel in 1948, thereby alienating the Arab states in that region.

Truman Doctrine (Greece and Turkey)

In a strongly worded speech to Congress, Truman declared, “I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” Journalists quickly dubbed this statement the “Truman Doctrine.” The president asked Congress to provide $400 million for economic and military aid, mostly to Greece but also to Turkey. After an emotional debate that resembled the one between interventionists and isolationists before World War II, the money was appropriated.

Critics from the left later charged that to whip up American support for the policy of containment, Truman overstated the Soviet threat to the United States. In turn, his statements inspired a wave of hysterical anti-Communism throughout the country. Perhaps so. Others, however, would counter that this argument ignores the backlash that likely would have occurred if Greece, Turkey, and other countries had fallen within the Soviet orbit with no opposition from the United States.

Marshall Plan

The Cold War accelerated in 1947 and 1948 as Americans actively fought Communism with dollars, reorganized the military and intelligence service and carefully avoided open war with the Soviets. Because Western Europe was again lying in ruins, American policy makers feared that, without immediate aid, western European states would, in desperation, turn to Communism. “The patient is sinking while the doctors deliberate,” declared Secretary of State George C. Marshall. In mid-1947 Marshall asked troubled European nations to draw up a program “directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.”

Marshall’s proposed aid program quickly got bogged down in debate. Moscow directed its European satellite states to reject the offer because it was designed to rebuild the Capitalist system.

The Soviets participated in the first planning meeting, then departed rather than share economic data and submit to Western controls on the expenditure of the aid. The remaining 16 nations hammered out a request that finally came to $17 billion for a four-year period. In early 1948 Congress, jarred into action by the Soviet-backed overthrow of Czechoslovakia, voted to fund the “Marshall Plan,” which helped underwrite the economic resurgence of Western Europe. It is generally regarded as one of the most successful foreign policy initiatives in U.S. history.

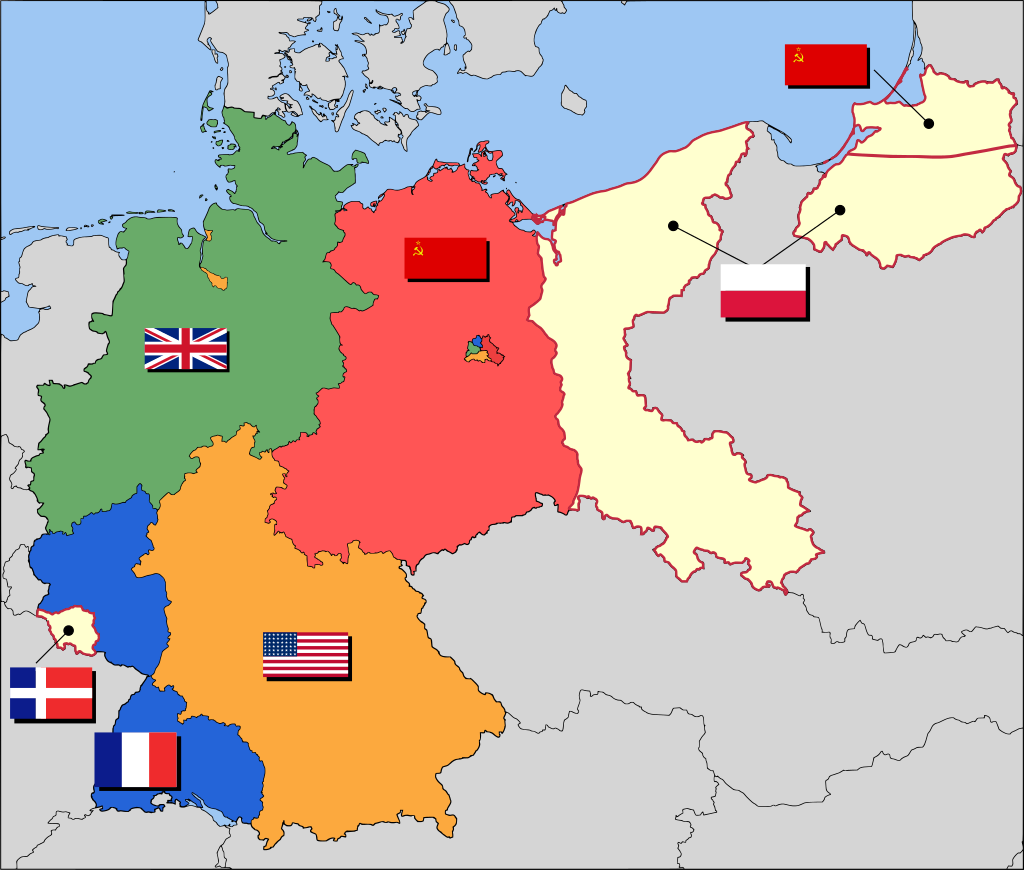

Occupation Zones and Berlin Airlift

Postwar Germany was a special problem. It had been divided into U.S., Soviet, British, and French zones of occupation, with the former German capital of Berlin (itself divided into four similar zones), near the center of the Soviet zone. When the Western powers announced their intention to create a consolidated federal state from their zones, Stalin responded. On June 24, 1948, Soviet forces blockaded Berlin, cutting off all road and rail access from the West.

American leaders feared that losing Berlin would be a prelude to losing Germany and subsequently all of Europe. Therefore, in a successful demonstration of Western resolve known as the Berlin Airlift, Allied air forces took to the sky, flying supplies into Berlin. U.S., French, and British planes delivered nearly 2,250,000 tons of goods, including food and coal. In what became a public relations windfall for his presidency, Truman kept up the airlift until Stalin lifted the blockade after 231 days and 277,264 flights.

NATO

By then, Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, and especially the Czech coup, had alarmed both Americans and Western Europeans. The result, was moving Marshall’s stalled economic plan through Congress and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Initiated by the Europeans, NATO was a military alliance to complement Marshall’s economic efforts at containment. The Norwegian historian Geir Lundestad has called it “empire by invitation.” In NATO an attack against one was to be considered an attack against all, to be met by appropriate force. NATO was the first peacetime “entangling alliance” with powers outside the Western hemisphere in American history.

NSC 68

The next year, the United States defined its defense aims clearly. The National Security Council (NSC) — the forum where the President, Cabinet officers, and other executive branch members consider national security and foreign affairs issues — undertook a full-fledged review of American foreign and defense policy. The resulting document, known as NSC-68, signaled a new direction in American security policy. Based on the assumption that “the Soviet Union was engaged in a fanatical effort to seize control of all governments wherever possible,” the document committed America to assist allied nations anywhere in the world that seemed threatened by Soviet aggression. After the start of the Korean War, a reluctant Truman approved the document. The United States proceeded to increase defense spending dramatically.

THE UNITED NATIONS

In 1945, following the Yalta Conference, representatives from fifty nations met in San Francisco to hammer out a United Nations agreement. It emerged as a three part system with a General Assembly representing each member state, a Secretariat to execute U.N. directives and a Security Council with six rotating members and five permanent members. The permanent members (France, China, Great Britain, The United States and Soviet Union) each held the power of absolute veto. The veto and the make-up of the members of the permanent members would play a crucial role in the future development of the Cold War.

Warsaw Pact

The Soviets would eventually respond to the Creation of NATO by creating the Warsaw Pact with its satellite nations. Though its stated goals were similar to NATOs, the Pact was actually used to crush anti-soviet uprisings in its member states. The Soviet Union’s entry into the nuclear club was unexpected and unwelcome to American analysts. The Americans responded by extending the doctrine of containment to the entire globe (from containing Soviet Communism to containing Global Communism) and by beginning development of a hydrogen bomb with much greater destructive power.

THE COLD WAR IN ASIA AND THE MIDDLE EAST

While seeking to prevent Communist ideology from gaining further adherents in Europe, the United States also responded to challenges elsewhere. In China, Americans worried about the advances of Mao Zedong and his Communist Party. During World War II, the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist forces waged a civil war even as they fought the Japanese. Chiang had been a wartime ally, but his government was hopelessly inefficient and corrupt. American policymakers had little hope of saving his regime and considered Europe vastly more important. With most American aid moving across the Atlantic, Mao’s forces seized power in 1949. Chiang’s government fled to the island of Taiwan. When China’s new ruler announced that he would support the Soviet Union against the “imperialist” United States, it appeared that Communism was spreading out of control, at least in Asia, as China fellto Mao.

The Fall of China

China's fall to Communism came as a surprise to most Americans. In retrospect, China’s leader during World War II, Chiang’s corrupt and inept handling of American aid during the war, made revolution inevitable. That the Americans misread China’s revolution as having been orchestrated from Moscow was unfortunate. China never did march to Moscow's tune and never would.

Korean War

The Korean War was the first serious test of containment and brought armed conflict between the United States and China. At the end of World War II the Soviets occupied the northern half of Korea, above the 38th parallel and the Americans occupied the southern half. Originally a matter of military convenience, the dividing line became more rigid as both major powers set up governments in their respective occupation zones and continued to support them even after departing.

In June 1950, after consultations with and having obtained the assent of the Soviet Union, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung dispatched his Soviet-supplied army across the 38th parallel and attacked southward, overrunning Seoul and pushing the South Koreans and Americans to Pusan and nearly out of the peninsula altogether. Truman, perceiving the North Koreans as Soviet pawns in the global struggle, readied American forces and ordered World War II hero General Douglas MacArthur to Korea. Meanwhile, the United States was able to secure a U.N. resolution branding North Korea as an aggressor. (The Soviet Union, which could have vetoed any action had it been occupying its seat on the Security Council, was boycotting the United Nations to protest a decision not to admit Mao’s new Chinese regime.)

MacArthur’s force made an amphibious landing at Inchon and pushed the North Koreans all the way back to the 38th parallel. When both Truman and the UN approved of reunifying Korea, MacArthur pushed the North Koreans all the way to the Chinese border. Thirty-three Chinese divisions poured over the border and pushed UN forces well below the 38th parallel. MacArthur publicly called for nuclear retaliation and a naval blockade against China.

U.N. forces, largely American, retreated once again in bitter fighting. Commanded by General Matthew B. Ridgway, they stopped the overextended Chinese, and slowly fought their way back to the 38th parallel. MacArthur’s public bluster got him fired. Cease-fire talks began and dragged on into 1952.

The Cold War stakes were high. Mindful of the European priority, the U.S. government decided against sending more troops to Korea and was ready to settle for the prewar status quo. The result was frustration among many Americans who could not understand the need for restraint. Truman’s popularity plunged to a 24-percent approval rating, the lowest to that time of any president since pollsters had begun to measure presidential popularity. Truce talks began in July 1951. The two sides finally reached an agreement in July 1953, during the first term of Truman’s successor, Dwight Eisenhower.

Video (00:03:28) USS Clamagore (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/d7N5CeXt)

Cold War struggles also occurred in the Middle East. The region’s strategic importance as a supplier of oil had provided much of the impetus for pushing the Soviets out of Iran in 1946. But two years later, the United States officially recognized the new state of Israel 15 minutes after it was proclaimed — a decision Truman made over strong resistance from Marshall and the State Department. The result was an enduring dilemma — how to maintain ties with Israel while keeping good relations with bitterly anti-Israeli (and oil-rich) Arab states.

EISENHOWER AND THE COLD WAR

![By Unknown or not provided (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3484)

By Unknown or not provided (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Video (00:02:42) Eisenhower (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=17698&xtid=43180&loid=94114)

In 1953, Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first Republican president in 20 years. A war hero rather than a career politician, he had a natural, common touch that made him widely popular. “I like Ike” was the campaign slogan of the time. After serving as Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Western Europe during World War II, Eisenhower had been army chief of staff, president of Columbia University, and military head of NATO before seeking the Republican presidential nomination. Skillful at getting people to work together, he functioned as a strong public spokesman and an executive manager somewhat removed from detailed policy making.

Despite disagreements on detail, he shared Truman’s basic view of American foreign policy. He, too, perceived Communism as a monolithic force struggling for world supremacy. In his first inaugural address, he declared, “Forces of good and evil are massed and armed and opposed as rarely before in history. Freedom is pitted against slavery, lightness against dark.”

The new president and his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, had argued that containment did not go far enough to stop Soviet expansion. Rather, a more aggressive policy of liberation was necessary, to free those subjugated by Communism. But when a democratic rebellion broke out in Hungary in 1956, the United States stood back as Soviet forces suppressed it.

Eisenhower’s “nuclear shield”

Eisenhower’s basic commitment to contain Communism remained, and to that end he increased American reliance on a nuclear shield. The United States had created the first atomic bombs and in 1950 Truman had authorized the development of a new and more powerful hydrogen bomb. Eisenhower, fearful that defense spending was out of control, reversed Truman’s NSC-68 policy of a large conventional military buildup. Relying on what Dulles called “massive retaliation,” the administration signaled it would use nuclear weapons if the nation or its vital interests were attacked.

In practice, however, the nuclear option could be used only against extremely critical attacks. Real Communist threats were generally peripheral. Eisenhower rejected the use of nuclear weapons in Indochina, when the French were ousted by Vietnamese Communist forces in 1954. In 1956, British and French forces attacked Egypt following Egyptian nationalization of the Suez Canal and Israel invaded the Egyptian Sinai. The president exerted heavy pressure on all three countries to withdraw. Still, the nuclear threat may have been taken seriously by Communist China, which refrained not only from attacking Taiwan, but from occupying small islands held by Nationalist Chinese just off the mainland. It may also have deterred Soviet occupation of West Berlin, which reemerged as a festering problem during Eisenhower’s last two years in office.

THE COLD WAR AT HOME

Not only did the Cold War shape U.S. foreign policy, it also had a profound effect on domestic affairs. Americans had long feared radical subversion. These fears could at times be overdrawn, and used to justify otherwise unacceptable political restrictions, but it also was true that individuals under Communist Party discipline and many “fellow traveler” hangers-on gave their political allegiance not to the United States, but to the international Communist movement, or, practically speaking, to Moscow. During the Red Scare of 1919-1920, the government had attempted to remove perceived threats to American society. After World War II, it made strong efforts against Communism within the United States. Foreign events, espionage scandals, and politics created an anti-Communist hysteria.

When Republicans were victorious in the midterm congressional elections of 1946 and appeared ready to investigate subversive activity, President Truman established a Federal Employee Loyalty Program. It had little impact on the lives of most civil servants, but a few hundred were dismissed, some unfairly.

HUAC

In 1947 the House Committee on Un-American Activities investigated the motion-picture industry to determine whether Communist sentiments were being reflected in popular films. When some writers (who happened to be secret members of the Communist Party) refused to testify, they were cited for contempt and sent to prison. After that, the film companies refused to hire anyone with a marginally questionable past.

Alger Hiss

In 1948, Alger Hiss, who had been an assistant secretary of state and an adviser to Roosevelt at Yalta, was publicly accused of being a Communist spy by Whittaker Chambers, a former Soviet agent. Hiss denied the accusation, but in 1950 he was convicted of perjury. Subsequent evidence indicates that he was indeed guilty.

The Rosenbergs

In 1949 the Soviet Union shocked Americans by testing its own atomic bomb. In 1950, the government uncovered a British-American spy network that transferred to the Soviet Union materials about the development of the atomic bomb. Two of its operatives, Julius Rosenberg and his wife Ethel, were sentenced to death. Attorney General J. Howard McGrath declared there were many American Communists, each bearing “the germ of death for society.”

The Second Red Scare was precipitated by both the fall of China and the Soviet atomic bomb. Americans were sure that espionage in the highest levels of government was the only explanation for such events. In this atmosphere the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was greatly expanded under J. Edgar Hoover and loyalty oaths were required of government employees. Real and high-level espionage did exist and was partly responsible for the Soviet nuclear success; however, Senator Joseph McCarthy undermined real efforts to address espionage through his anti-communist antics.

Joe McCarthy

McCarthy used HUAC to level charges against the media, the government, academics, political enemies and all challengers. He was known for waving stacks of paper in front of committees and cameras and claiming to have “lists” of government officials sympathetic to the Communist Party.

McCarthy gained power when the Republican Party won control of the Senate in 1952. As a committee chairman, he now had a forum for his crusade. Relying on extensive press and television coverage, he continued to search for treachery among second-level officials in the Eisenhower administration. Enjoying the role of a tough guy doing dirty but necessary work, he pursued presumed Communists with vigor.

In reality McCarthy had seized on anti-Communism to enhance his mediocre political career. Fear of McCarthy even kept President Eisenhower from challenging him. McCarthy overstepped himself by challenging the U.S. Army when one of his assistants was drafted. Television brought the hearings into millions of homes and Americans saw McCarthy’s savage tactics for the first time; public support began to wane. The Republican Party, which had found McCarthy useful in challenging a Democratic administration when Truman was president, began to see him as an embarrassment. The Senate finally condemned him for his conduct.

During McCarthy's reign of terror, anyone challenging McCarthy was a suspected Communist; after it, anyone hunting for Communists was suspected of McCarthyism.

McCarthy in many ways represented the worst domestic excesses of the Cold War. As Americans repudiated him, it became natural for many to assume that the Communist threat at home and abroad had been grossly overblown. As the country moved into the 1960s, anti-Communism became increasingly suspect, especially among intellectuals and opinion-shapers. The real damage of Joseph McCarthy was that real Communist threats in the U.S. could now operate more openly as Americans became fearful of being accused of McCarthyism were they to confront these very real threats.

THE POSTWAR ECONOMY: 1945-1960

In the decade and a half after World War II, the United States experienced phenomenal economic growth and consolidated its position as the world’s richest country. Gross national product (GNP), a measure of all goods and services produced in the United States, jumped from about $200 billion in 1940 to $300 billion in 1950 to more than $500 billion in 1960. More and more Americans now considered themselves part of the middle class.

The growth had different sources. The economic stimulus provided by large-scale public spending for World War II helped get it started. Two basic middle-class needs did much to keep it going. The number of automobiles produced annually quadrupled between 1946 and 1955. A housing boom, stimulated in part by easily affordable mortgages for returning servicemen, fueled the expansion. The rise in defense spending as the Cold War escalated also played a part.

After 1945 the major corporations in America grew even larger. There had been earlier waves of mergers in the 1890s and in the 1920s; in the 1950s another wave occurred. Franchise operations like McDonald’s fast-food restaurants allowed small entrepreneurs to make themselves part of large, efficient enterprises. Big American corporations also developed holdings overseas, where labor costs were often lower.

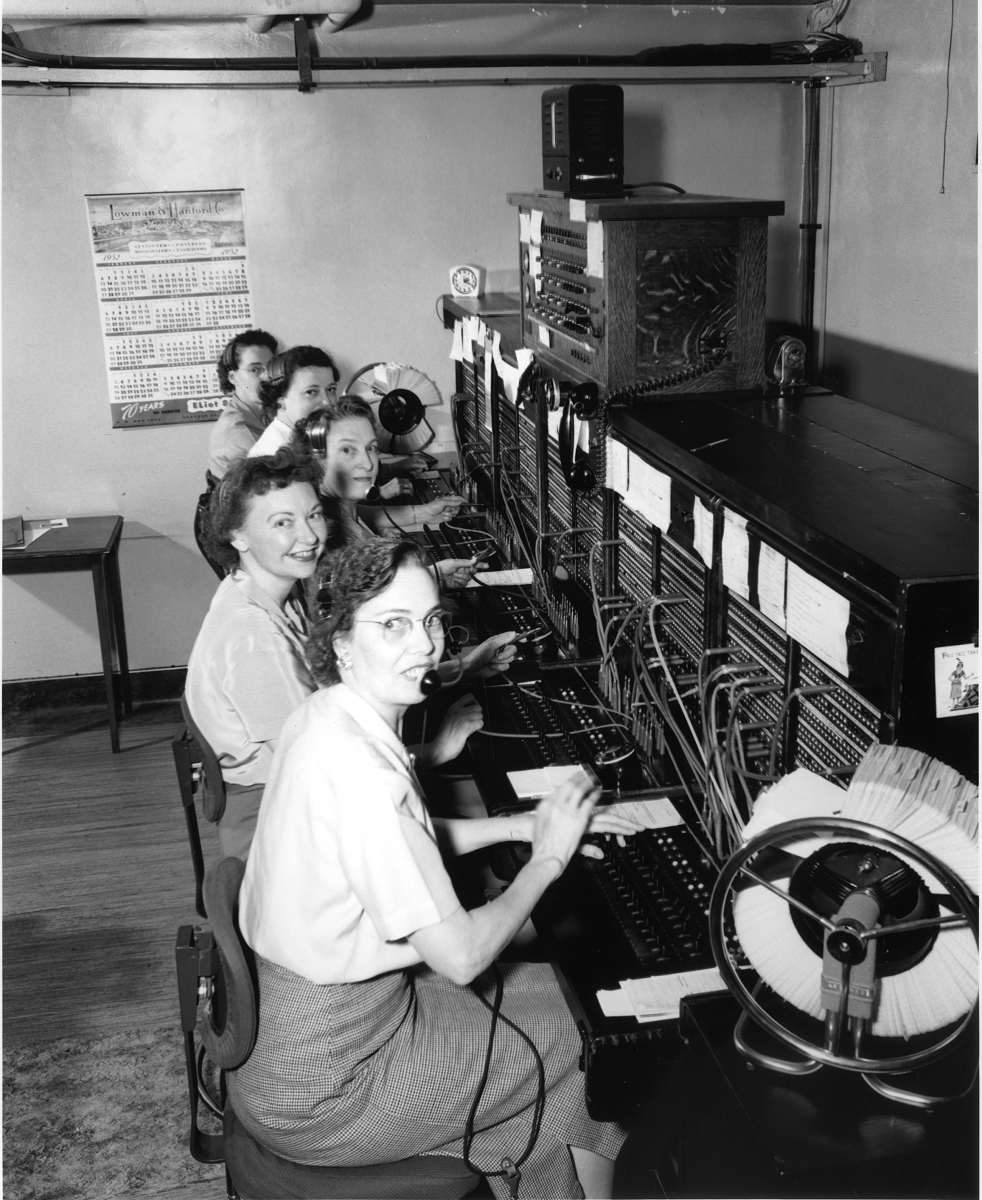

Workers found their own lives changing as industrial America changed. Fewer workers produced goods; more provided services. As early as 1956 a majority of employees held white-collar jobs, working as managers, teachers, salespersons, and office operatives. Some firms granted a guaranteed annual wage, long-term employment contracts, and other benefits. With such changes, labor militancy was undermined and some class distinctions began to fade.

Americans on the Move

Farmers — at least those with small operations — faced tough times. Gains in productivity led to agricultural consolidation, and farming became a big business. More and more family farmers left the land.

Other Americans moved too. The West and the Southwest grew with increasing rapidity, a trend that would continue through the end of the century. Sun Belt cities like Houston, Texas; Miami, Florida; Albuquerque, New Mexico; and Phoenix, Arizona, expanded rapidly. Los Angeles, California, moved ahead of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the third largest U.S. city and then surpassed Chicago, metropolis of the Midwest. The 1970 census showed that California had displaced New York as the nation’s largest state. By 2000, Texas had moved ahead of New York into second place.

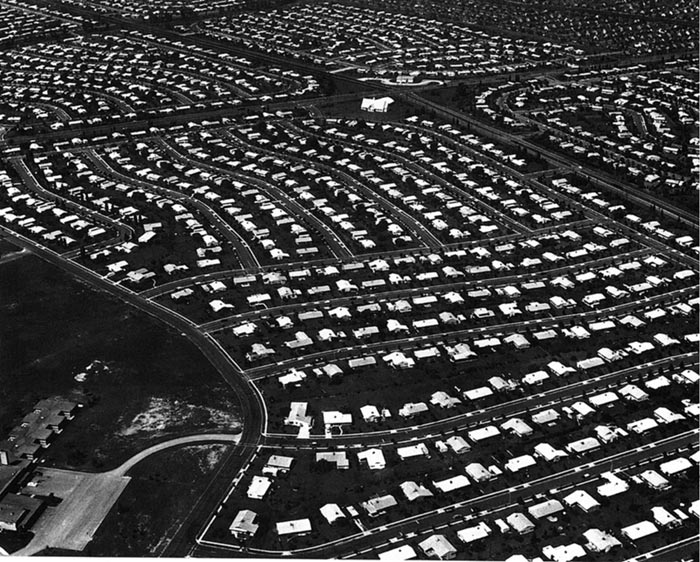

Suburbs

An even more important form of movement led Americans out of inner cities into new suburbs, where they hoped to find affordable housing for the larger families spawned by the postwar baby boom. Developers like William J. Levitt built new communities — with homes that all looked alike — using the techniques of mass production. Levitt’s houses were prefabricated — partly assembled in a factory rather than on the final location — and modest, but Levitt’s methods cut costs and allowed new owners to possess a part of the American dream.

As suburbs grew, businesses moved into the new areas. Large shopping centers containing a great variety of stores changed consumer patterns. The number of these centers rose from eight at the end of World War II to 3,840 in 1960. With easy parking and convenient evening hours, customers could avoid city shopping entirely. An unfortunate by-product was the “hollowing out” of formerly busy urban cores.

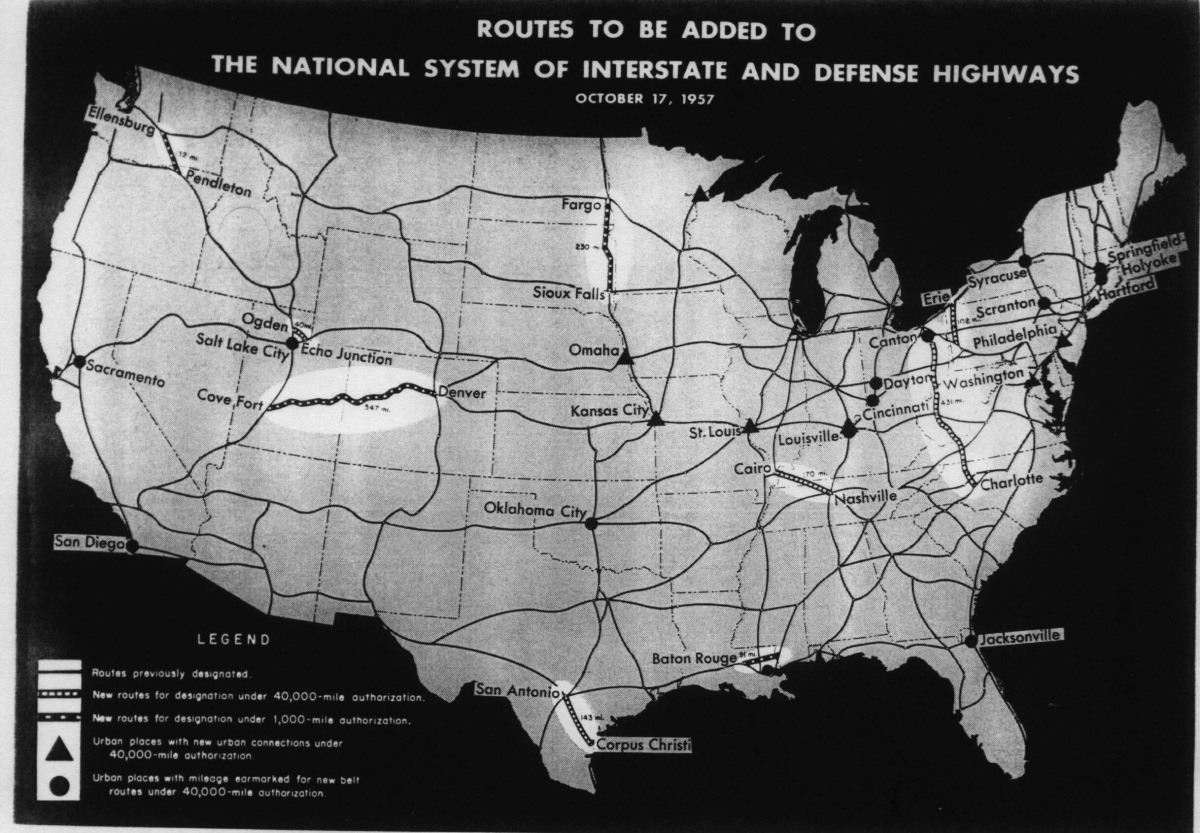

Highways

New highways created better access to the suburbs and its shops. The Highway Act of 1956 provided $26 billion, the largest public works expenditure in U.S. history, to build more than 40,000 miles of limited access interstate highways to link the country together. Driving the Highway Act was Eisenhower’s goal to provide rapid deployment of military assets, and easier evacuation of major cities in war-time.

Television

Television, too, had a powerful impact on social and economic patterns. Developed in the 1930s, it was not widely marketed until after the war. In 1946 the country had fewer than 17,000 television sets. Three years later consumers were buying 250,000 sets a month, and by 1960 three-quarters of all families owned at least one set. In the middle of the decade, the average family watched television four to five hours a day. Popular shows for children included Howdy Doody Time and The Mickey Mouse Club; older viewers preferred situation comedies like I Love Lucy and Father Knows Best. Americans of all ages became exposed to increasingly sophisticated advertisements for products said to be necessary for the good life. The cultural homogenization that begun in the 1920s with radio and movie theaters, sped up noticeably as Americans listened to, watched and imitated the same programming on a daily basis.

Video (00:02:37) Ensemble video: TV (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/m7J6XtSd)

TRUMAN’S FAIR DEAL

The Fair Deal was the name given to President Harry Truman’s domestic program. Building on Roosevelt’s New Deal, Truman believed that the federal government should guarantee economic opportunity and social stability. He struggled to achieve those ends in the face of fierce political opposition from legislators determined to reduce the role of government.

Truman’s first priority in the immediate postwar period was to make the transition to a peacetime economy. Servicemen wanted to come home quickly, but once they arrived they faced competition for housing and employment. The G.I. Bill, passed before the end of the war, helped ease servicemen back into civilian life by providing benefits such as guaranteed loans for home-buying and financial aid for industrial training and university education.

More troubling was labor unrest. As war production ceased, many workers found themselves without jobs. Others wanted pay increases they felt were long overdue. In 1946, 4.6 million workers went on strike, more than ever before in American history. They challenged the automobile, steel, and electrical industries.When they took on the railroads and soft-coal mines, Truman intervened to stop union excesses, but in so doing he alienated many workers.

While dealing with immediately pressing issues, Truman also provided a broader agenda for action. Less than a week after the war ended, he presented Congress with a 21-point program, which provided for protection against unfair employment practices, a higher minimum wage, greater unemployment compensation, and housing assistance. In the next several months, he added proposals for health insurance and atomic energy legislation. But this scattershot approach often left Truman’s priorities unclear.

Republicans were quick to attack. In the 1946 congressional elections they asked, “Had enough?” and voters responded that they had. Republicans, won majorities in both houses of Congress for the first time since 1928 and were determined to reverse the liberal direction of the previous 14 years.

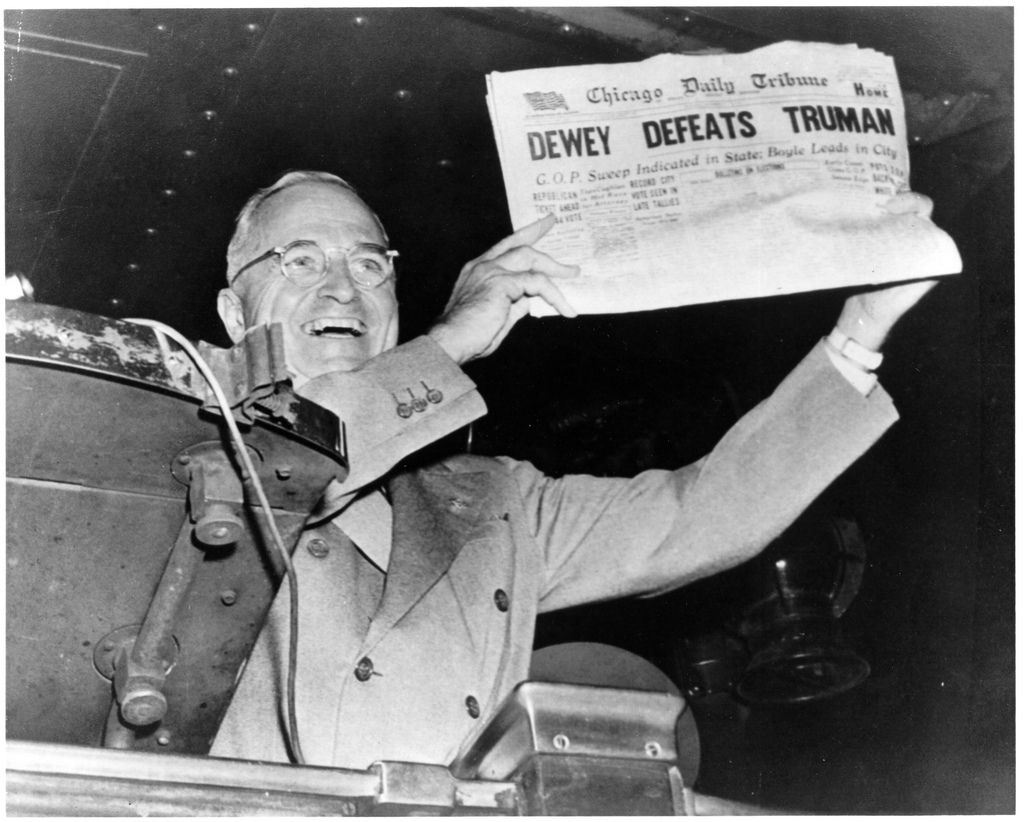

Election of 1948

Truman fought with the Congress as it cut spending and reduced taxes. In 1948 he sought reelection, despite polls indicating that he had little chance. After a vigorous campaign, Truman scored one of the greatest upsets in American politics, defeating the Republican nominee, Thomas Dewey, governor of New York. Reviving the old New Deal coalition, Truman held on to labor, farmers, and African-American voters.

When Truman finally left office in 1953, his Fair Deal was but a mixed success. In July 1948 he banned racial discrimination in federal government hiring practices and ordered an end to segregation in the military. The minimum wage had risen, and social security programs had expanded. A housing program brought some gains but left many needs unmet. National health insurance, aid-to-education measures, reformed agricultural subsidies, and his legislative civil rights agenda never made it through Congress. The president’s pursuit of the Cold War, ultimately his most important objective, made it especially difficult to develop support for social reform in the face of intense opposition.

EISENHOWER’S APPROACH

When Dwight Eisenhower succeeded Truman as president, he accepted the basic framework of government responsibility established by the New Deal, but sought to hold the line on programs and expenditures. He termed his approach “dynamic conservatism” or “modern Republicanism,” which meant, he explained, “conservative when it comes to money, liberal when it comes to human beings.” A critic countered that Eisenhower appeared to argue that he would “strongly recommend the building of a great many schools ... but not provide the money.”

Eisenhower’s first priority was to balance the budget after years of deficits. He wanted to cut spending and taxes and maintain the value of the dollar. Republicans were willing to risk unemployment to keep inflation in check. Reluctant to stimulate the economy too much, they saw the country suffer three economic recessions in the eight years of the Eisenhower presidency, but none was very severe.

In other areas, the administration transferred control of offshore oil lands from the federal government to the states. It also favored private development of electrical power rather than the public approach the Democrats had initiated during the Depression. In general, its orientation was sympathetic to business.

Compared to Truman, Eisenhower had only a modest domestic program. When he was active in promoting a bill, it likely was to trim the New Deal legacy a bit — as in reducing agricultural subsidies or placing mild restrictions on labor unions. His disinclination to push fundamental change in either direction was in keeping with the spirit of the generally prosperous Fifties. He was one of the few presidents who left office as popular as when he entered it.

THE CULTURE OF THE 1950s

Video (00:07:47) : The Fabulous Fifties (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=47585&loid=411449)

American culture in the 1950s was a culture of fear, conformity, hope, economic expansion, and youthful celebration. Americans feared nuclear weapons and taught their children to “duck and cover.” President Eisenhower envisioned a system of interstate highways to connect large cities and allow easy evacuation and the movement of military equipment. The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 began the largest public works project in American History—with far-reaching consequences. The result was that the demand for automobiles skyrocketed, rail travel dwindled and the inner city began to decay as suburbs (accessible by the new highways) reached ever-further from the city.

Spending Spree

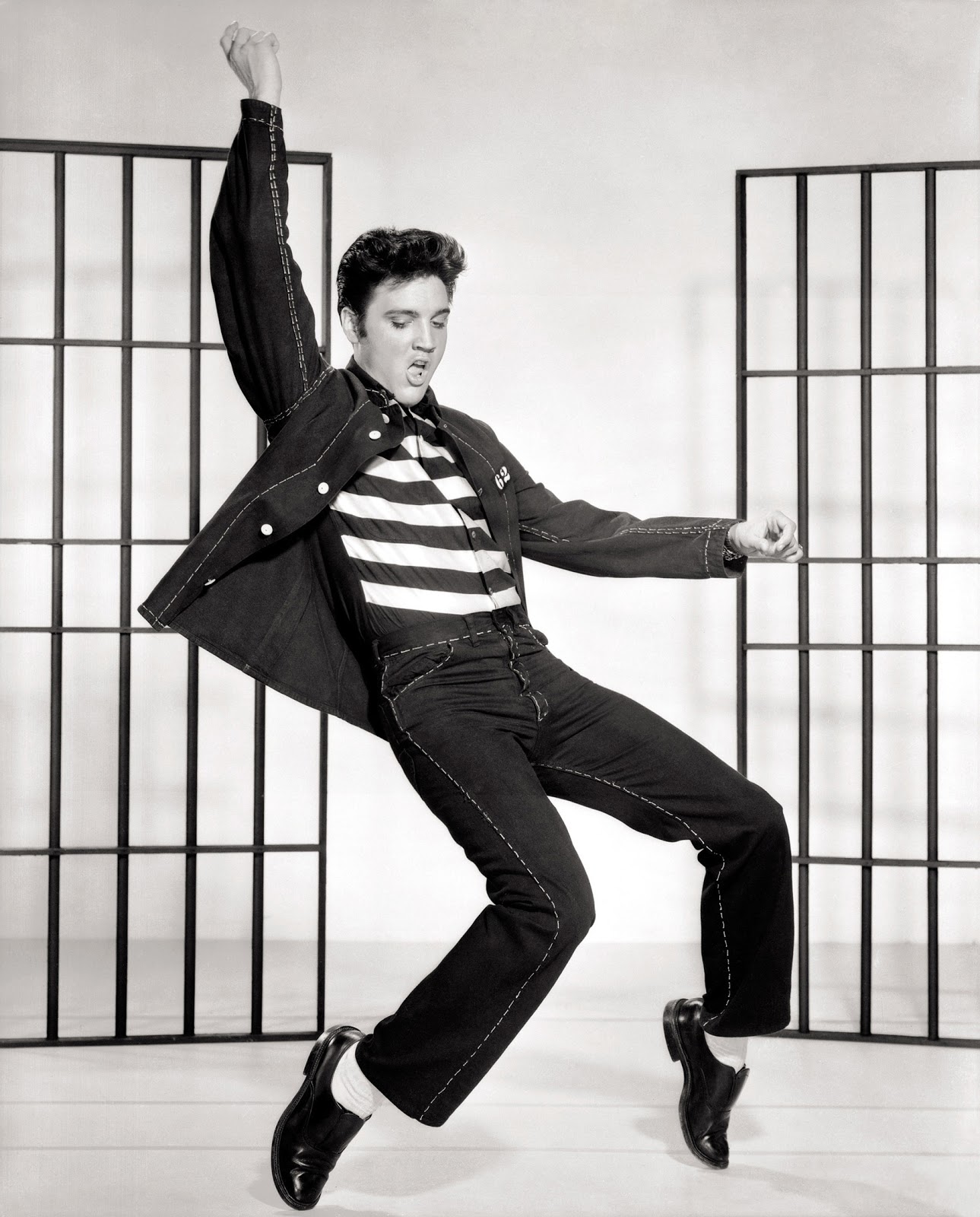

Having little or nothing to spend their paychecks on during World War II, Americans went on a buying spree which spurred industrial output and kept the Depression from returning. Americans bought televisions, moved to the expanding suburbs, lived in row housing and worked for “big” companies. The “G.I. Bill” gave returning soldiers access to education and housing on the cheap which also spurred the growth of the suburbs. Black Americans introduced yet another new form of music, “Rock and Roll,” which scandalized white Americans who viewed it as vulgar and loaded with sexual overtones. When Colonel Parker found a young white man (Elvis Presley) who could effectively perform this new music, it took young Americans by storm.

During the 1950s, many cultural commentators pointed out that a sense of uniformity pervaded American society. Conformity, they asserted, was numbingly common for most Americans. Though men and women had been forced into new employment patterns during World War II, once the war was over, traditional roles were reaffirmed. Men expected to be the breadwinners in each family; women, even when they worked, assumed their proper place was at home. In his influential book, The Lonely Crowd, sociologist David Riesman called this new society “other-directed,” characterized by conformity, but also by stability. Television, still very limited in the choices it gave its viewers, contributed to the homogenizing cultural trend by providing young and old with a shared experience reflecting accepted social patterns of dress, behavior and expectation.

![By Alden Jewell (1951 Nash Ambassador Custom 4-Door Sedan) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3621)

By Alden Jewell (1951 Nash Ambassador Custom 4-Door Sedan) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Video (00:02:01) Ensemble Video: Leisure (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/p6CNm74G)

Countercultural beginnings

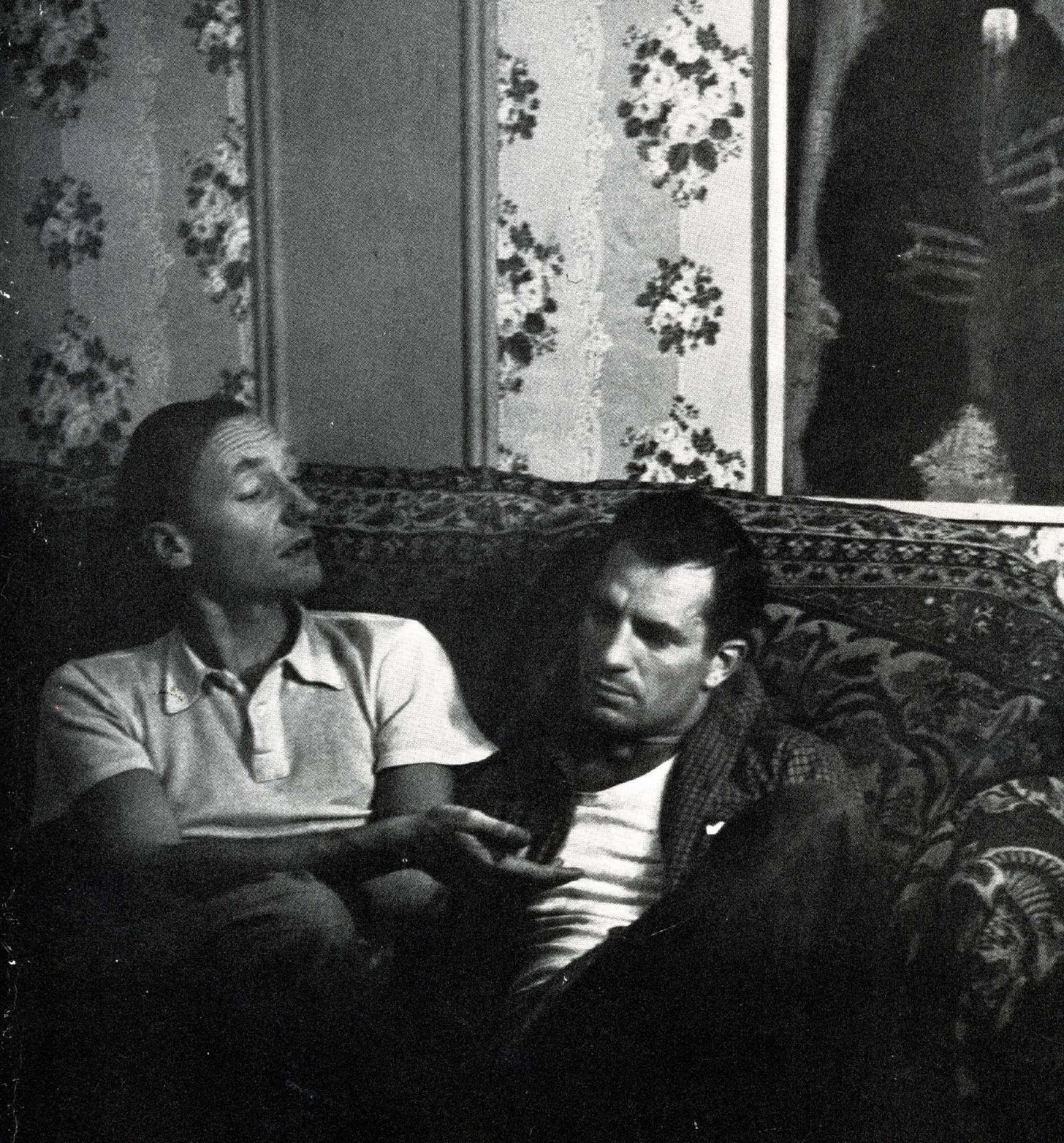

Yet beneath this seemingly bland surface, small, but important segments of American society seethed with rebellion. A number of writers, collectively known as the “Beat Generation,” went out of their way to challenge the patterns of respectability and shock the rest of the culture. Stressing spontaneity and spirituality, they preferred intuition over reason, Eastern mysticism over Western institutionalized religion.

The literary work of the beats displayed their sense of alienation and quest for self-realization. Jack Kerouac typed his best-selling novel On the Road on a 75-meter roll of paper. Lacking traditional punctuation and paragraph structure, the book glorified the possibilities of the free life. Poet Allen Ginsberg gained similar notoriety for his poem “Howl,” a scathing critique of modern, mechanized civilization. When police charged that it was obscene and seized the published version, Ginsberg successfully challenged the ruling in court.

Rock and Roll

Musicians and artists rebelled as well. Tennessee singer Elvis Presley was the most successful of several white performers who popularized a sensual and pulsating style of African-American music, which began to be called “rock and roll.” At first, he outraged middle-class Americans with his ducktail haircut and undulating hips. But in a few years his performances would seem relatively tame alongside the antics of later performers such as the British Rolling Stones. Similarly, it was in the 1950s that painters like Jackson Pollock discarded easels and laid out gigantic canvases on the floor, then applied paint, sand, and other materials in wild splashes of color. All of these artists and authors, whatever the medium, provided models for the wider and more deeply felt social revolution of the 1960s.