Chapter 17 - World War II

TOTAL VIDEO (00:50:360)

WAR AND UNEASY NEUTRALITY

Video (00:03:39) FDR (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36219&loid=408818)

Though slaughtering pigs and destroying produce did not end the Great Depression, slaughtering people and expanding production did. Hitler's rise to power brought with it frightening rhetoric about superior and inferior races, territorial expansion and a resurgence of the nationalism that had helped sink the world into global war twenty years earlier. As Germany remilitarized, built up its war machine and jettisoned the peace agreements of World War One, surrounding nations began to rebuild their own militaries. Each engaged in deficit spending and found their economies improving as a result. All of this seemed to fit the new economic theories of John Maynard Keynes. Keynes suggested that in the modern economy, it was necessary for government to engage in massive deficit spending in order to put money into the economy and put people to work. War production would do just that. As FDR looked warily to the east at German territorial expansion and west at Japanese expansion, he began to cautiously prepare an isolationist nation for possible action. The result was a steady climb out of depression beginning in 1939 as Americans began building more ships, more planes and more tanks—just in case.

Tensions in Asia

Though westerners traditionally view Hitler's invasion of Poland in 1939 as the beginning of the Second World War, in reality, the Second World War may well have started and ended in Asia. From before the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 to the mushroom cloud over Nagasaki in 1945, American and East-Asian interests, fortunes and destinies had been bound together in ways that could not have been foreseen on either side of the Pacific.

Since before the Spanish/American War, the Japanese had been working to modernize their military forces, largely as the result of being forced into a humiliating trade agreement by American warships in the 1850s. These efforts paid off when, in 1905, the Japanese fleet resoundingly defeated the Russian fleet in the Russo/Japanese War. The Japanese quickly found that their objective of military modernization naturally paired up with their lack of raw materials and their desire for expansion to make them the “rising sun” of Asia in the first half of the twentieth century. Japanese expansion into Manchuria, Korea and French-Vietnam brought war to South-East Asia years before Hitler rolled over Poland in the West.

Once again, the United States found itself looking at gross violations of human rights, but this time the situation involved an ascendant power (Japan) rather than a descendant power (Spain). As a substantial supplier of Japanese raw materials (especially oil), the U.S. found itself in a position to put economic pressure on the Japanese by cutting off shipments in the face of continued Japanese aggression in Asia.

Talk of war between the two was rumored and the Americans expected that an attack, if it came at all, would be upon their naval base in the Philippines. When the attack finally came at Pearl Harbor, it galvanized the country as nothing before or since. Americans were willing to expend lives and treasure until the Japanese surrendered, and they were prepared for a very long haul.

Tensions in Europe

In Europe, Italian dreams of restoring the Roman Empire encouraged Benito Mussolini, to enlarge Italy’s boundaries in Libya and in 1935 Italy Ethiopia was conquered. German repudiation of the Treaty of Versailles from the previous war, also caused European nerves to fray. Germany reoccupied the Rhineland (demilitarized by the Treaty of Versailles) in 1936. In 1938, Hitler incorporated Austria into the German Reich and demanded cession of the German-speaking Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia. As most thought that the Versailles treaty had been unfair to Germany and that the Great War had been a mistake, they (especially Great Britain) hoped that Hitler's 1938 invasion of Czechoslovakia to gather in ethnic Germans would satisfy him. Accordingly, France and Great Britain did essentially nothing in response. Despite German promises to the contrary, the whole of Czechoslovakia was soon overrun and Hitler began denouncing Poland. France and Great Britain quickly made a treaty with Poland to deter further German expansion. In a weird twist, Hitler made a secret treaty with his arch enemies, the Soviets, to jointly invade, occupy and divide Poland. Thus emboldened, Hitler invaded in 1939 and World War II was “officially” on.

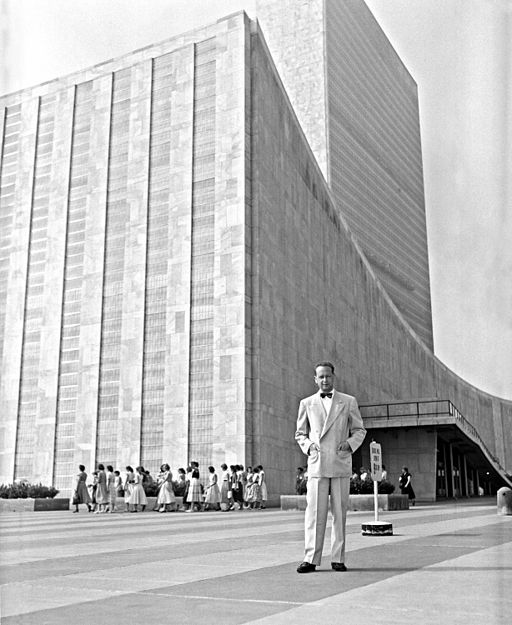

![From the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3598)

From the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The United States, disillusioned by the failure of the crusade for democracy in World War I, announced that in no circumstances could any country involved in the conflict look to it for aid. Neutrality legislation, enacted piecemeal from 1935 to 1937, prohibited trade in arms with any warring nations, required cash for all other commodities, and forbade American flagged merchant ships from carrying those goods. The objective was to prevent, at almost any cost, the involvement of the United States in a foreign war.

With the Nazi conquest of Poland in 1939 and the outbreak of World War II, isolationist sentiment increased, even though Americans clearly favored the victims of Hitler’s aggression and supported the Allied democracies, Britain and France. Roosevelt could only wait until public opinion regarding U.S. involvement was altered by events.

Blitzkrieg and the Battle of Britain

In the twenty short years since the last global war, advances in technology completely changed the face of war. While World War One is remembered for months of stalemate and trench warfare, World War II became known for the swift, fluid movement of forces over vast amounts of territory. Using the Blitzkrieg (Lightning War) the German military made quick work of Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and France, causing a hasty retreat to the Beach at Dunkirk where 300,000 French and British troops were evacuated to England. Within months, the German Army accomplished what it failed to do during four years of fighting in World War One. Hitler immediately began preparing for an invasion of the British Isles by bombing British airfields, then, British cities, in what became known as the “Battle for Britain.” Less than 1,000 British aircraft, with the aid of a new technology called “radar,” successfully defended against more than 2,500 German bombers. Then, incomprehensibly, Hitler turned on his Soviet allies and invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, in what surely was one of his biggest blunders of the war. This drew precious resources away from the West coast of France and bought time for the British.

American Neutrality

In the mid-1930s, New Dealer Isolationists watched warily as Fascism overtook Germany, Italy and Spain. When the Italians invaded Ethiopia in 1935, Congress quickly enacted, and Roosevelt signed, a series of Neutrality Acts to ensure that the United States would not be caught up in another European conflict. The acts allowed the President to forbid the shipping of any arms to belligerent nations. The United States joined Canada in a Mutual Board of Defense, and aligned with the Latin American republics in extending collective protection to the nations in the Western Hemisphere.

Video (00:02:04) Ensemble video: Despairingly Excessive Gloom (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/y8J9Lkd5&sa=D&ust=1487261740107000&usg=AFQjCNHCvdTvI4koT9x0WBkpk7QN59UslA)

Congress, confronted with the mounting crisis, voted immense sums for rearmament, and in September 1940 passed the first peacetime conscription bill ever enacted in the United States. In that month also, Roosevelt concluded a daring executive agreement with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The United States gave the British Navy 50 “overage” destroyers in return for British air and naval bases in Newfoundland and the North Atlantic.

The 1940 presidential election campaign demonstrated that the isolationists, while vocal, were a minority. Roosevelt’s Republican opponent, Wendell Wilkie, leaned toward intervention. Thus the November election yielded another majority for the president, making Roosevelt the first, and last, U.S. chief executive to be elected to a third term.

In early 1941, Roosevelt got Congress to approve the Lend-Lease Program, which enabled him to transfer arms and equipment to any nation (notably Great Britain, later the Soviet Union and China) deemed vital to the defense of the United States. Total Lend-Lease aid by war’s end would amount to more than $50,000 million.

Most remarkably, in August, he met with Prime Minister Churchill off the coast of Newfoundland. The two leaders issued a “joint statement of war aims,” which they called the Atlantic Charter. Bearing a remarkable resemblance to Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, it called for these objectives: no territorial aggrandizement; no territorial changes without the consent of the people concerned; the right of all people to choose their own form of government; the restoration of self-government to those deprived of it; economic collaboration between all nations; freedom from war, from fear, and from want for all peoples; freedom of the seas; and the abandonment of the use of force as an instrument of international policy. America was now neutral in name only.

After the invasion of Poland in 1939, Roosevelt asked Congress to allow the sale of arms to France and England on a cash-and-carry basis. As Britain ran out of money and the Battle of Britain intensified, Roosevelt asked Congress to approve “Lend-Lease” which would effectively trade American war materials for the rights to British bases around the world. By this time, of course, German submarines were sinking so much American shipping that an undeclared war already existed in the Atlantic. Roosevelt authorized armed escorts for Atlantic transports and issued “shoot on sight orders” for all shipping that might encounter Nazi Submarines.

Video (00:02:42) Submarine (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/i6K2Wgo9)

By the summer of 1941, Roosevelt had come to understand that America would have to join the war effort against Nazi Germany, and the sooner the better, lest Great Britain be lost and the Germans become entrenched. One great difficulty was that war was clearly brewing in the Pacific as well. American codebreakers had deciphered the Japanese diplomatic code and knew that an attack was coming, soon. When that attack came, would Roosevelt be able to justify a war against Germany as well; or would the American public demand that he focus on the Japanese only and risk Hitler overrunning all of Europe?

Pearl Harbor

While most Americans anxiously watched the course of the European war, tension mounted in Asia. Taking advantage of an opportunity to improve its strategic position, Japan boldly announced a “new order” in which it would exercise hegemony over all of the Pacific. Battling for survival against Nazi Germany, Britain was unable to resist, abandoning its concession in Shanghai and temporarily closing the Chinese supply route from Burma. In the summer of 1940, Japan won permission from the weak Vichy government in France to use airfields in northern Indochina (North Vietnam). That September the Japanese formally joined the Rome-Berlin Axis. The United States countered with an embargo on the export of scrap iron to Japan.

In July 1941 the Japanese occupied southern Indochina (South Vietnam), signaling a probable move southward toward the oil, tin, and rubber of British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. The United States, in response, froze Japanese assets and initiated an embargo on the one commodity Japan needed above all others — oil.

General Hideki Tojo became prime minister of Japan that October. In mid-November, he sent a special envoy to the United States to meet with Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Among other things, Japan demanded that the United States release Japanese assets and stop U.S. naval expansion in the Pacific. Hull countered with a proposal for Japanese withdrawal from all its conquests. The swift Japanese rejection on December 1 left the talks stalemated.

On the morning of December 7, Japanese carrier-based planes executed a devastating surprise attack against the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Twenty-one ships were destroyed or temporarily disabled; 323 aircraft were destroyed or damaged; 2,388 soldiers, sailors, and civilians were killed. However, the U.S. aircraft carriers that would play such a critical role in the ensuing naval war in the Pacific were at sea and not anchored at Pearl Harbor.

American opinion, still divided about the war in Europe, was unified overnight by what President Roosevelt called “a day that will live in infamy.” On December 8, Congress declared a state of war with Japan. For his part, Roosevelt considered Germany to be the far greater threat. He feared, however that Americans, now united against Japan, would not tolerate military action against Germany.

Roosevelt’s dilemma was resolved shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Within days of the attack, Hitler, impressed that the Japanese could launch such a devastating attack, judged that America was weak and declared war on the United States to encourage the “inferior” Japanese. This, probably Hitler’s greatest blunder of the war, allowed Roosevelt to proceed in either theatre of war as he saw fit. Since there seemed no imminent threat of invasion of the U.S. by either, Japan or Germany, Roosevelt decided to concentrate on winning in Europe while fighting a holding action in the Pacific.

In this, Roosevelt had an unexpected ally—the Depression. Americans had always been ones to tinker and the Depression made it that much more important to keep old equipment working, hence, the American military consisted of seasoned backyard mechanics with plenty of American know-how to keep field equipment operational. Additionally, two million CCC boys from the 1930s had lived for years under army discipline, eating army food, and doing army-hard work. Never before had such a ready-made force of fighting men been available.

MOBILIZATION FOR TOTAL WAR

American industry churned out war materials at an unprecedented rate and Americans changed the way they lived to achieve victory. This “Arsenal of Democracy,” as Churchill called it, produced, by war’s end, twice as much as Germany and Japan combined. At Henry Ford’s Willow Run plant, a B-24 bomber could be produced in one hour. At the Kaiser Shipyards, construction of a transport ship dropped from over three months to just two weeks. Over three-and-a-half years, war industry achieved staggering production goals — 300,000 aircraft, 5,000 cargo ships, 60,000 landing craft, 86,000 tanks. Average Americans pitched in by planting “Victory Gardens” so that farm goods could feed allied armies. Scrap metal and rubber drives, rationing and “going without” all produced in Americans, a sense that they were contributing; some even donated hair for use as “cross hairs” in bomb sites.

Video (00:01:32) Ensemble Video: Locomotive(https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/x9M8Baq5)

Total strength of the U.S. armed forces at the end of the war was more than 12 million. All the nation’s activities — farming, manufacturing, mining, trade, labor, investment, communications, even education and cultural undertakings — were in some fashion brought under new and enlarged governmental controls.

Video (00:07:17) The World at War(https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36221&loid=37743)

As a result of Pearl Harbor and the fear of Asian espionage, Americans also committed what was later recognized as an act of intolerance: the internment of Japanese Americans. In February 1942, nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans residing in California were removed from their homes and interned behind barbed wire in 10 temporary camps, later to be moved to “relocation centers” outside isolated Southwestern towns.

Nearly 63 percent of these Japanese Americans were American-born U.S. citizens. A few were Japanese sympathizers, but no evidence of espionage ever surfaced. Others volunteered for the U.S. Army and fought with distinction and valor in two infantry units on the Italian front. Some served as interpreters and translators in the Pacific.

In 1983 the U.S. government acknowledged the injustice of internment with limited payments to those Japanese-Americans of that era who were still living.

THE WAR IN NORTH AFRICA AND EUROPE

Soon after the United States entered the war, the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union (at war with Germany since June 22, 1941) decided that their primary military effort was to be concentrated in Europe.

Video (00:02:52) Allied Strategy (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36221&loid=37744)

Throughout 1942, British and German forces fought inconclusive back-and-forth battles across Libya and Egypt for control of the Suez Canal. But on October 23, British forces commanded by General Bernard Montgomery struck at the Germans from El Alamein. Equipped with a thousand tanks, many made in America, they defeated General Erwin Rommel’s army in a grinding two-week campaign. On November 7, American and British armed forces landed in French North Africa. Squeezed between forces advancing from east and west, the Germans were pushed back and, after fierce resistance, surrendered in May 1943.

The year 1942 was also the turning point on the Eastern Front. The Soviet Union, suffering immense losses, stopped the Nazi invasion at the gates of Leningrad and Moscow. In the winter of 1942-43, the Red Army defeated the Germans at Stalingrad (Volgograd) and began the long offensive that would take them to Berlin in 1945.

Cultural Earthquake

The war produced a cultural earthquake as so much stimuli for change came in such a short time. The Depression was clearly over and people were putting money in the bank. Indeed, they had little to spend it on as rationing kept luxury goods scarce. Millions of blacks flooded out of the South to work in Northern and Western war industries alongside white women, forever changing the racial mixture of large cities. Housing shortages, especially in these cities, caused a huge demand for construction. Black Americans began to expect better treatment as they contributed to the war effort. Philip Randolph threatened to march on Washington to protest government discrimination in defense contracts. Roosevelt capitulated and signed an executive order preventing discrimination in both government hiring and in defense contracts. The tired notion that blacks could not stand in the face of battle (clearly disproved in the Civil War by the Massachusetts 54th) was again challenged by the Tuskegee Airmen.

This squadron of black fighter pilots never lost an escorted bomber in 15,000 African sorties. The Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) began in 1942 with the first “freedom rides” and lunch-counter sit-ins which ended segregation in numerous northern businesses and which foreshadowed a Civil Rights movement scarcely a decade away.

Video (00:01:04) Ensemble video: Diner Car (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Nj2k7LZt)

Italy

In Europe, Josef Stalin was increasingly vocal in demanding a western front to relieve pressure on his Soviet units in the East. To his consternation, the Allies invaded North Africa instead. After defeating Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps and saving the Suez Canal from German occupation in 1942, the Mediterranean was opened to allied shipping, but Stalin was not appeased. Roosevelt wished to open a front in France but British Prime Minister Churchill, fearing a replay of the carnage of World War One, favored tightening the noose around Germany without an amphibious landing. In a compromise, the Americans and British stormed ashore in Sicily in July, 1943. However, because Italy is a narrow peninsula, fewer German divisions were needed to defend it. Again Stalin was unimpressed.

During that time, Benito Mussolini fell from power in Italy. His successors began negotiations with the Allies and surrendered immediately after the invasion of the Italian mainland in September. However, the German Army had by then taken control of the peninsula. The fight against Nazi forces in Italy was bitter and protracted. Rome was not liberated until June 4, 1944. As the Allies slowly moved north, they built airfields from which they made devastating air raids against railroads, factories, and weapon emplacements in southern Germany and central Europe, including the oil installations at Ploesti, Romania.

Video (00:04:09) D-Day to Berlin (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36221&loid=37746)

D-Day

U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower had been appointed Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe. Late in 1943 the Allies, after much debate over strategy, decided to open a front in France to compel the Germans to divert far larger forces from the Soviet Union. In this, Stalin finally got his second front when, on June 6, 1944, the largest amphibious landing to date took place in Normandy, France. In just the first day the Allies put nearly 200,000 men and more than a thousand tanks on the beaches, delivered by more than 6,000 allied ships floating offshore. From this point, the Germans were pushed back steadily. On August 25 Paris was liberated.

A brief exception to the Allied advance was the “Battle of the Bulge”—a tank adventure which only served to leave the German homeland without armored protection as its gasoline reserves were exhausted in the battle. In March, the Americans and British were across the Rhine and the Russians advancing irresistibly from the East. In April of 1945, Hitler committed suicide. On May 7 Germany surrendered unconditionally.

THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC

Video (00:05:27) Victory in the Pacific (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36221&loid=37747)

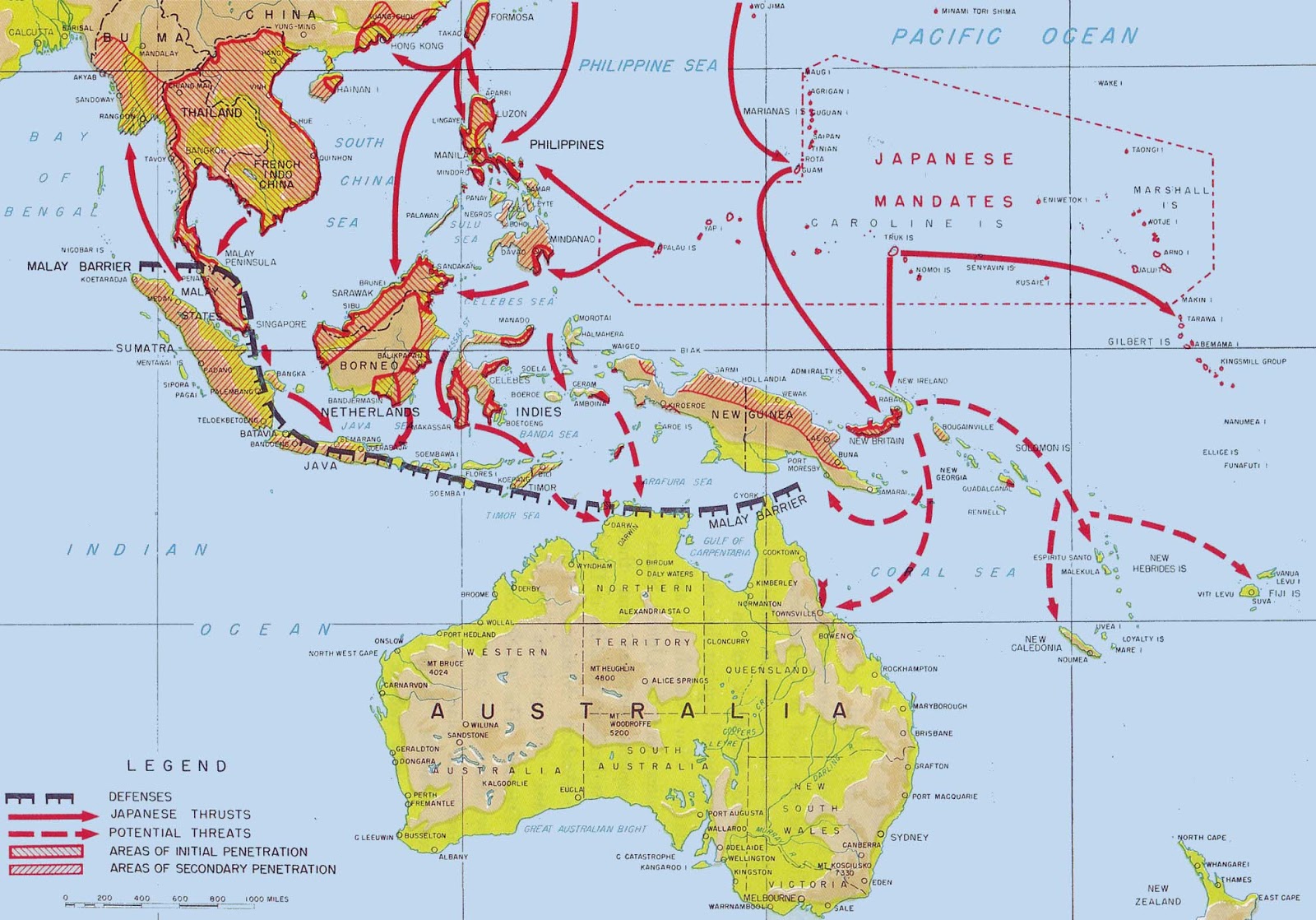

The first year of American involvement was challenging. In the first half of 1942 the Japanese took Hong Kong, Malaya, the Philippines, Singapore, Burma and New Guinea. U.S. troops were forced to surrender in the Philippines in early 1942, but the Americans rallied in the following months. General James “Jimmy” Doolittle led U.S. Army bombers on a raid over Tokyo in April; it had little actual military significance, but gave Americans an immense psychological boost.

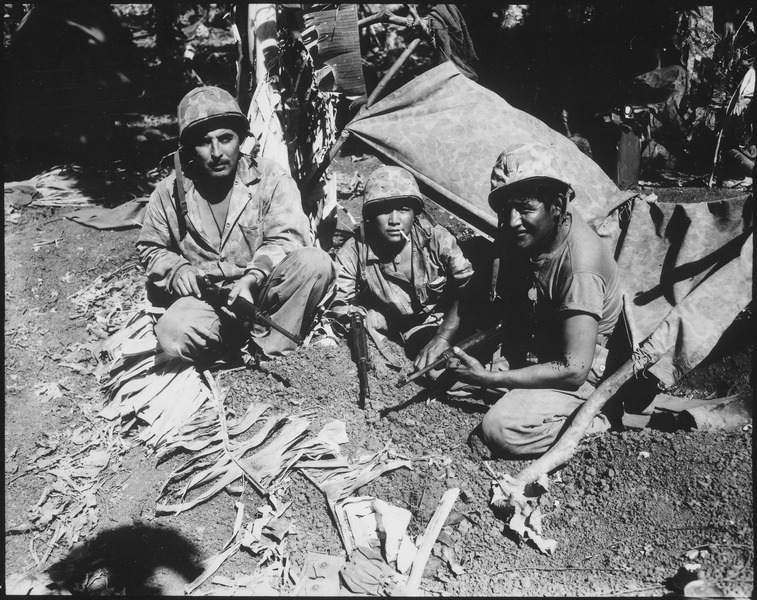

While the Americans had broken the Japanese diplomatic code before the war began, their own code was impenetrable as they used Navaho “Code Talkers” to send and decipher messages.

In May, at the Battle of the Coral Sea — the first naval engagement in history in which all the fighting was done by carrier-based planes — a Japanese naval invasion fleet sent to strike at southern New Guinea and Australia was turned back by a U.S. task force in a close battle. A few weeks later, the naval Battle of Midway in the central Pacific resulted in the first major defeat of the Japanese Navy, which lost four aircraft carriers. Ending the Japanese advance across the central Pacific, Midway was the turning point. While Midway had been the turning point in the Pacific, a slow, bloody campaign of island-hopping lay ahead.

Video (00:11:42) Ensemble Video: U.S.S. Yorktown (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/x8R3AjEg)

The six-month land and sea battle for the island of Guadalcanal (August 1942-February 1943) was the first major U.S. ground victory in the Pacific. For most of the next two years, American and Australian troops fought their way northward from the South Pacific and westward from the Central Pacific, capturing the Solomons, the Gilberts, the Marshalls, and the Marianas in a series of amphibious assaults The ultimate goal was an invasion of Japan itself followed by unconditional surrender. This, it was thought, could prove more costly than all previous Pacific action combined—if carried out.

THE POLITICS OF WAR

The beginning of the end of the war may have been in Hitler's third error—killing off and/or harassing intellectuals out of Germany. Many of these ended up in American military think tanks and some even worked on the Atomic Bomb. When coupled with his invasion of the Soviet Union and declaration of war against the United States, Hitler's chances of success dwindled geometrically with each bungle.

Allied military efforts were accompanied by a series of important international meetings on the political objectives of the war. In January 1943 at Casablanca, Morocco, an Anglo-American conference decided that no peace would be concluded with the Axis and its Balkan satellites except on the basis of “unconditional surrender.” This term, insisted upon by Roosevelt, sought to assure the people of all the fighting nations that no separate peace negotiations would be carried on with representatives of Fascism and Nazism and there would be no compromise of the war’s idealistic objectives. Axis propagandists, of course, used it to assert that the Allies were engaged in a war of extermination.

Cairo

At Cairo, in November 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill met with Nationalist Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek to agree on terms for Japan, including the relinquishment of gains from past aggression. At Tehran, shortly afterward, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin made basic agreements on the postwar occupation of Germany and the establishment of a new international organization, the United Nations.

Yalta

In February 1945, the three Allied leaders met again at Yalta (now in Ukraine), with victory seemingly secure. There, the Soviet Union secretly agreed to enter the war against Japan three months after the surrender of Germany. In return, the USSR would gain effective control of Manchuria and receive the Japanese Kurile Islands as well as the southern half of Sakhalin Island. The eastern boundary of Poland was set roughly at the Curzon line of 1919, thus giving the USSR half its prewar territory. Discussion of reparations to be collected from Germany — payment demanded by Stalin and opposed by Roosevelt and Churchill — was inconclusive. Specific arrangements were made concerning Allied occupation in Germany and the trial and punishment of war criminals. Also at Yalta it was agreed that the great powers in the Security Council of the proposed United Nations should have the right of veto in matters affecting their security.

Two months after his return from Yalta, Franklin Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage while vacationing in Georgia. Few figures in U.S. history have been so deeply mourned, and for a time the American people suffered from a numbing sense of irreparable loss. Vice President Harry Truman, former senator from Missouri, succeeded him.

Video (00:04:29) Truman(https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=449871)

WAR, VICTORY, AND THE BOMB

The final battles in the Pacific were among the war’s bloodiest. In June 1944, the Battle of the Philippine Sea effectively destroyed Japanese naval air power, forcing the resignation of Japanese Prime Minister Tojo. General Douglas MacArthur — who had reluctantly left the Philippines two years before to escape Japanese capture — returned to the islands in October.

Battle of the Philippine Sea

Beginning with the battle for Midway, the Japanese had been slowly pushed back from island to island. The Japanese were merely able to replace the four carriers they'd lost in the battle, while the Americans produced more than a dozen additional carriers during the war. Once the U.S. had captured the Marianas atoll—at about the same time as the Normandy invasion—they began bombing the Japanese mainland. Three more Japanese carriers were lost in the “Battle of the Philippine Sea” that same month. Japan sent three battle fleets to the area in response; and in October, these were destroyed in the largest naval battle in history. All that remained now was the Japanese mainland, suicide (kamikaze) pilots, and the American determination to wrest an unconditional surrender from Japan.

Next, the United States set its sight on the strategic island of Iwo Jima in the Bonin Islands, about halfway between the Marianas and Japan. The Japanese, trained to die fighting for the Emperor, made suicidal use of natural caves and rocky terrain. U.S. forces took the island by mid-March, but not before losing the lives of some 6,000 U.S. Marines. Nearly all the Japanese defenders perished. By now the United States was undertaking extensive air attacks on Japanese shipping and airfields and wave after wave of incendiary bombing attacks against Japanese cities.

At Okinawa (April 1-June 21, 1945), the Americans met even fiercer resistance. With few of the defenders surrendering, the U.S. Army and Marines were forced to wage a war of annihilation. Waves of Kamikaze suicide planes pounded the offshore Allied fleet, inflicting more damage than at Leyte Gulf. Japan lost 90-100,000 troops and probably as many Okinawan civilians. U.S. losses were more than 11,000 killed and nearly 34,000 wounded. Most Americans saw the fighting as a preview of what they would face in a planned invasion of Japan.

Potsdam

The heads of the U.S., British, and Soviet governments met at Potsdam, a suburb outside Berlin, from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to discuss operations against Japan, the peace settlement in Europe, and a policy for the future of Germany. Perhaps presaging the coming end of the alliance, they had no trouble on vague matters of principle or the practical issues of military occupation, but reached no agreement on many tangible issues, including reparations.

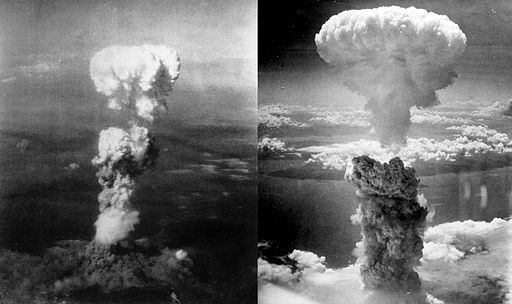

The day before the Potsdam Conference began, U.S. nuclear scientists engaged in the secret Manhattan Project exploded an atomic bomb near Alamogordo, New Mexico. The test was the culmination of three years of intensive research in laboratories across the United States. It lay behind the Potsdam Declaration, issued on July 26 by the United States and Britain, promising that Japan would neither be destroyed nor enslaved if it surrendered. If Japan continued the war, however, it would meet “prompt and utter destruction.” President Truman, calculating that an atomic bomb might be used to gain Japan’s surrender more quickly and with fewer casualties than an invasion of the mainland, ordered that the bomb be used if the Japanese did not surrender by August 3.

In 1939, Princeton professor Albert Einstein had warned President Roosevelt of the probability of a German effort to build a “super” bomb which theoretically could create a huge explosion using atomic energy. To Roosevelt, the thought of such a weapon in the hands of the Germans was unbearable. In 1941 he set about winning the race to develop this weapon by instituting a $2 billion secret effort known as the “Manhattan Project.” Winning an unprecedented 3rd term in 1940, followed by a 4th in 1944, Roosevelt kept the secret even from his own Vice Presidents—first, Henry Wallace, then, Harry Truman. Roosevelt’s sudden death in April of 1945 thrust news of, and responsibility for, this new weapon into the lap of Harry Truman. By this time it was clear that Germany would lose the war and not produce an atomic weapon. However, the specter of invading the Japanese mainland, and the American goal of unconditional surrender gave new meaning to the bomb’s development and potential use. Perhaps an invasion could be avoided and the surrender attained by using this weapon.

A committee of U.S. military and political officials and scientists had considered the question of targets for the new weapon. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson argued successfully that Kyoto, Japan’s ancient capital and a repository of many national and religious treasures, be taken out of consideration. Hiroshima, a center of war industries and military operations, became the first objective.

On August 6, 1945 80,000 Japanese lives ended in Hiroshima; this was followed three days later with an additional 60,000 as another atomic weapon fell on Nagasaki. Japan surrendered. The invasion never took place.

Video (00:02:13) Atomic Bombs (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36221&loid=37748)

On August 6, a U.S. plane, the Enola Gay, dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. On August 9, a second atomic bomb was dropped, this time on Nagasaki. The bombs destroyed large sections of both cities, with massive loss of life. On August 8, the USSR declared war on Japan and attacked Japanese forces in Manchuria. On August 14, Japan agreed to the terms set at Potsdam. On September 2, 1945, Japan formally surrendered. Americans were relieved that the bomb hastened the end of the war. The realization of the full implications of nuclear weapons’ awesome destructiveness would come later.

Video (00:03:26) After the War (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=36221&loid=37749)

Within a month, on October 24, the United Nations came into existence following the meeting of representatives of 50 nations in San Francisco, California. The constitution they drafted outlined a world organization in which international differences could be discussed peacefully and common cause made against hunger and disease. In contrast to its rejection of U.S. membership in the League of Nations after World War I, the U.S. Senate promptly ratified the U.N. Charter by an 89 to 2 vote. This action confirmed the end of the spirit of isolationism as a dominating element in American foreign policy.

Hitler had risen to power in 1933, partly on the popularity of his fanatical anti-Semitism. His “final solution” involved the rounding up, and extermination, of 6 million Jews along with 4 million other “undesirables.” The United States knew of Hitler’s “final solution” as early as 1942 but refused to allow many Jewish refugees into the U.S. or to bomb the extermination camps that had been photographed from reconnaissance planes. It was reasoned that the best way to help those in the camps was to focus all efforts on victory. In November 1945 at Nuremberg, Germany, the criminal trials of 22 Nazi leaders, provided for at Potsdam, took place. Before a group of distinguished jurists from Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States, the Nazis were accused not only of plotting and waging aggressive war but also of violating the laws of war and of humanity in the systematic genocide, known as the Holocaust, of European Jews and other peoples. The trials lasted more than 10 months. Twenty-two defendants were convicted, 12 of them sentenced to death. Similar proceedings would be held against Japanese war leaders.

Implications of World War II

The lasting implications of the Second World War center on race, gender, the bombing of civilians, and economics.

Black Americans made substantive contributions to the war effort and expected to find a grateful nation waiting for their return. What they found was a nation of segregated schools, transportation, restaurants and washrooms—a particularly glaring insult given the fact that they'd been fighting Hitler's racist agenda, precisely because it was a racist agenda. A Civil Rights movement was incubated by this war and would be born in less than a decade.

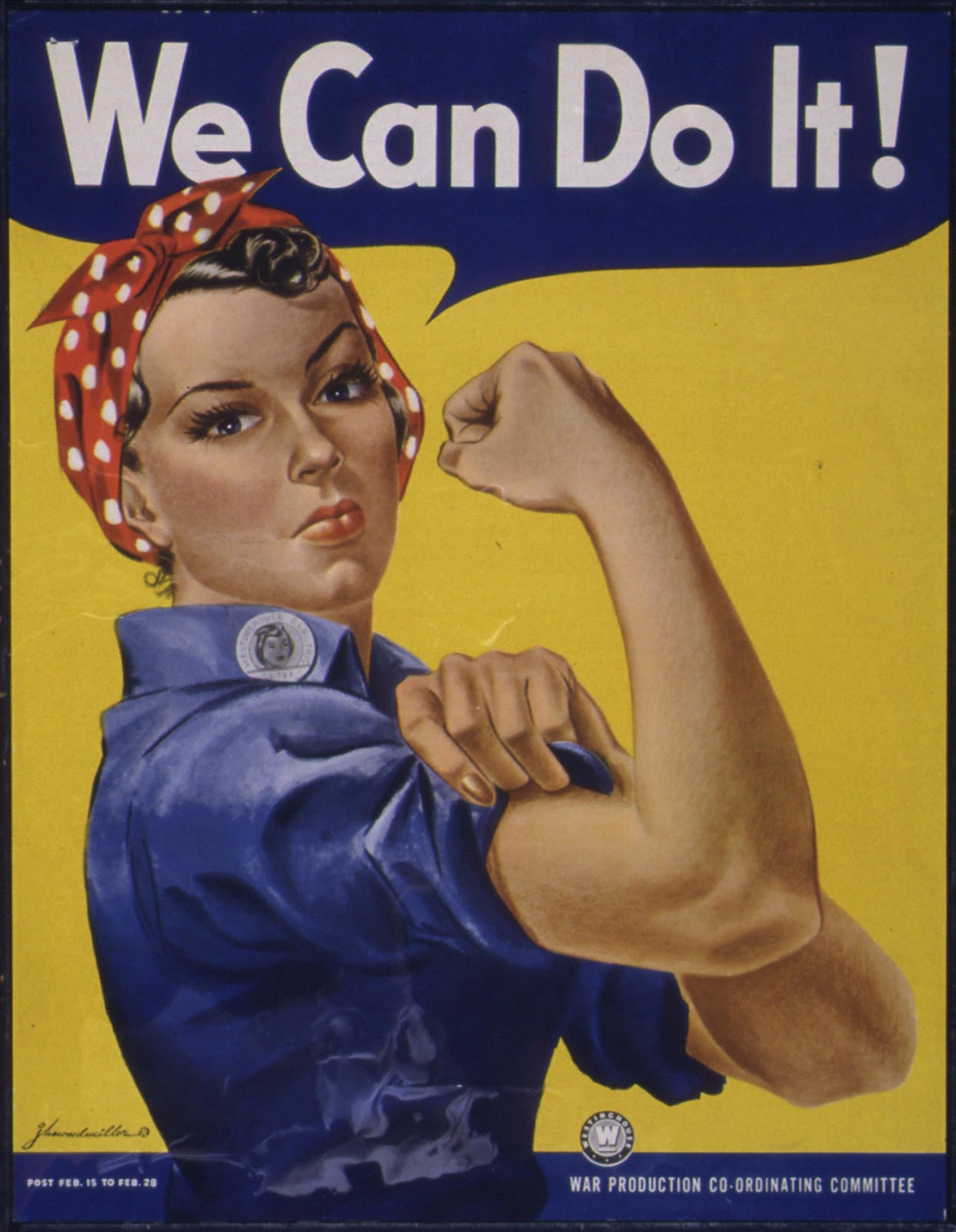

Women had gone to work in greater numbers than ever before and found that they could work at “male” jobs and save the world in the process. Many did not wish to give up their new found freedom and paychecks when the boys came marching home—though most did. A new, women’s rights movement was also on the horizon, though it would lack the clear vision and dedication of the Suffrage or Civil Rights movements.

The bombing of civilians was first introduced by Hitler's Germany in the “Battle for Britain.” The allies returned the same in the form of napalm (jellied gasoline) raids on German cities. Once this line had been crossed, it was not such a large leap to the use of atomic weapons on Japanese cities. In fact, more deaths occurred in Dresden and Tokyo due to napalm than were recorded in Hiroshima and Nagasaki; “dead is dead,” whether from napalm or radiation. Hence forward, global conflicts would threaten whole civilizations.

Finally, the economy roared back to life due to massive war production. This uncomfortable truth has kept economists busy trying to figure out ways of maintaining a healthy economy short of mass-slaughter.