Chapter 20 The New Conservatism and a New World Order

“I have always believed that there was some divine plan that placed this great continent between two oceans to be sought out by those who were possessed of an abiding love of freedom and a special kind of courage.”

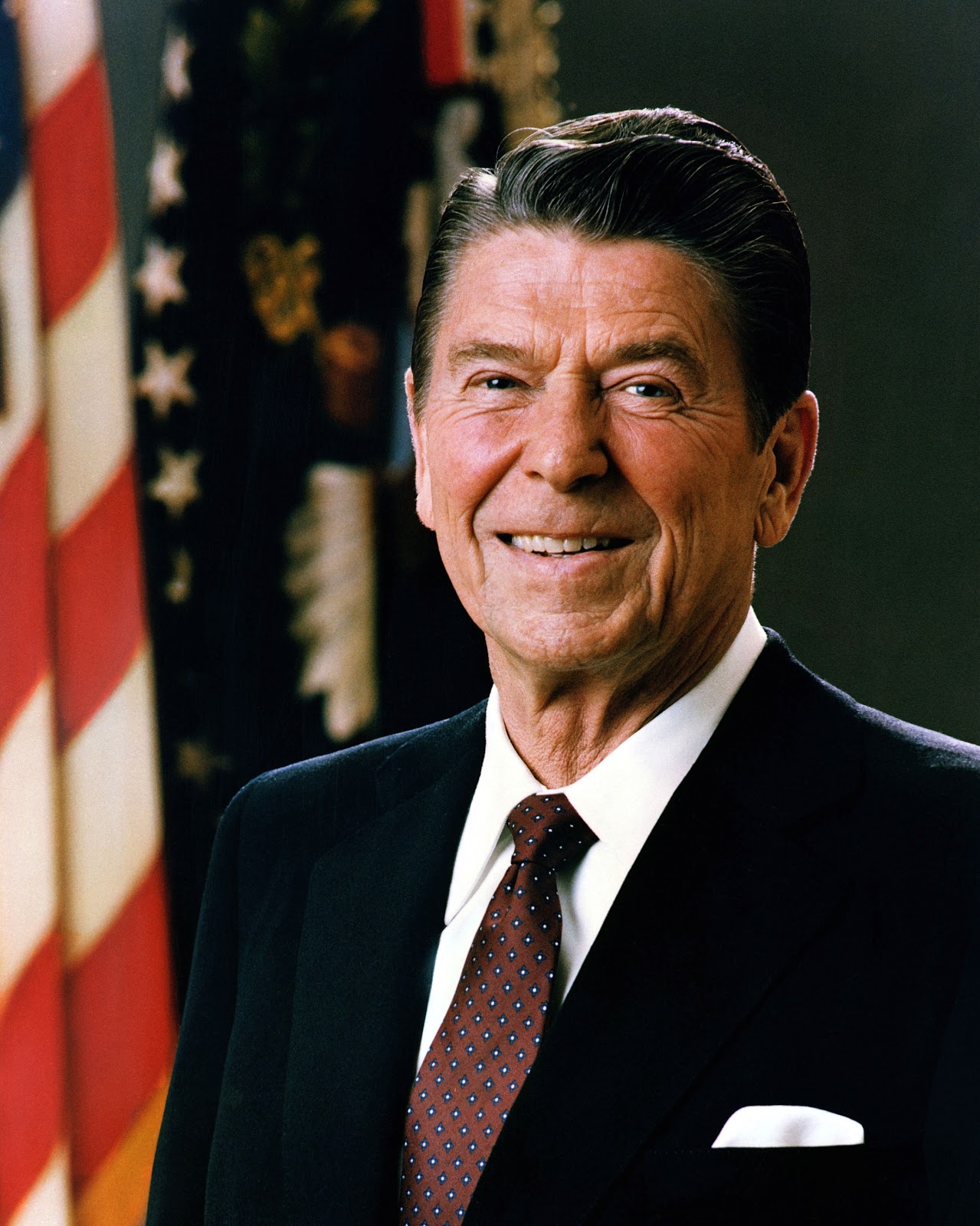

California Governor Ronald Reagan, 1974

Total Video (01:10:36)

THE FORD INTERLUDE

Nixon’s vice president, Gerald Ford (appointed to replace Agnew), was an unpretentious man who had spent most of his public life in Congress. His first priority was to restore trust in the government. However, feeling it necessary to head off the spectacle of a possible prosecution of Nixon, he issued a blanket pardon to his predecessor. Although it was perhaps necessary, the move was nonetheless unpopular.

In public policy, Ford followed the course Nixon had set. Economic problems remained serious, as inflation and unemployment continued to rise. Ford first tried to reassure the public, much as Herbert Hoover had done in 1929. When that failed, he imposed measures to curb inflation, which sent unemployment above 8 percent. A tax cut, coupled with higher unemployment benefits, helped a bit but the economy remained weak.

Video (00:03:45): The Presidents : Ford (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=94126)

In foreign policy, Ford adopted Nixon’s strategy of détente. Perhaps its major manifestation was the Helsinki Accords of 1975, in which the United States and Western European nations effectively recognized Soviet hegemony in Eastern Europe in return for Soviet affirmation of human rights. The agreement had little immediate significance, but over the long run may have made maintenance of the Soviet empire more difficult. Western nations effectively used periodic “Helsinki review meetings” to call attention to various abuses of human rights by Communist regimes of the Eastern bloc. One of Ford’s greatest disappointments was his failure to live up to Nixon’s secret agreement to support South Vietnam militarily when the North invaded in 1975. The Congress simply would not go along with an agreement that few knew anything about; ultimately, the American people were tired of the war.

Video (00:06:25): Communist Victory in Vietnam/Human Rights Victory in Helsinki (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=8398&loid=412127)

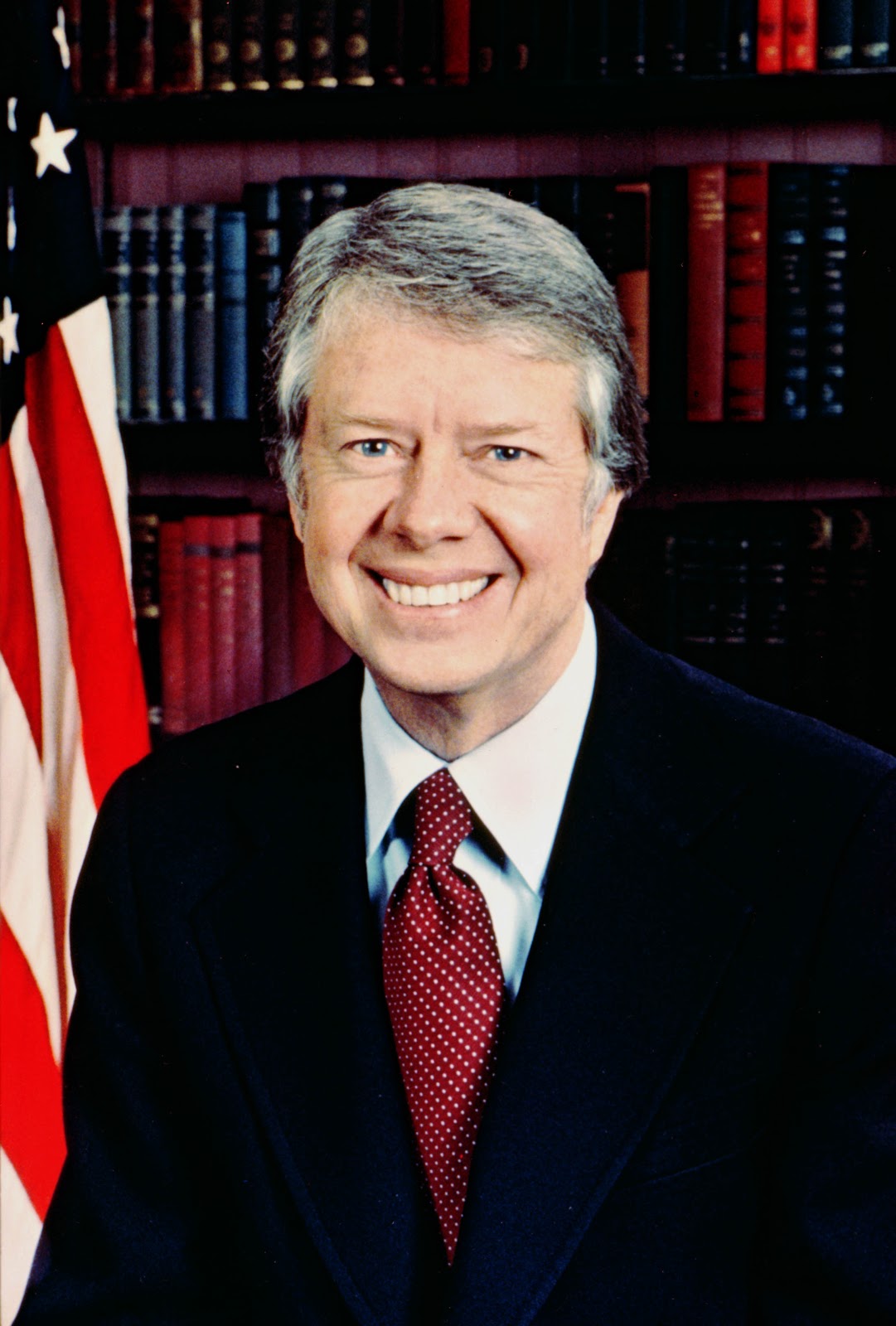

THE CARTER YEARS

Jimmy Carter, former Democratic governor of Georgia, won the presidency in 1976. Portraying himself during the campaign as an outsider to Washington politics, he promised a fresh approach to governing, but his lack of experience at the national level complicated his tenure from the start. A naval officer and engineer by training, he often appeared to be a technocrat, when Americans wanted someone more visionary to lead them through troubled times.

Economic Inertia

In economic affairs, Carter at first permitted a policy of deficit spending. Inflation rose to 10 percent a year when the Federal Reserve Board, responsible for setting monetary policy, increased the money supply to cover deficits. Carter responded by cutting the budget, but cuts affected social programs at the heart of Democratic domestic policy. In mid-1979, anger in the financial community practically forced him to appoint Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve. Volcker was an “inflation hawk” who increased interest rates in an attempt to halt price increases, at the cost of negative consequences for the economy.

Carter’s Energy Policy

Carter also faced criticism for his failure to secure passage of an effective energy policy. He presented a comprehensive program, aimed at reducing dependence on foreign oil, that he called the “moral equivalent of war.” The oil embargo in 1973 by the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) had taught Americans that dependence on foreign oil could mean long lines at the pumps, inflation, and frustration. Accordingly, one of Carter’s first actions was to create the Cabinet-level Department of Energy and to adopt fuel saving measures such as the 55 mph speed limit on federal highways. Thermostats were adjusted in all federal office buildings and some very preliminary efforts were made to find alternative sources of energy. Opponents thwarted Carter’s plan in Congress.

Deregulation

Though Carter called himself a populist, his political priorities were never wholly clear. He endorsed government’s protective role, but then began the process of deregulation, the removal of governmental controls in economic life. Arguing that some restrictions over the course of the past century limited competition and increased consumer costs, he favored decentralized control in the oil, airline, railroad, and trucking industries.

Carter’s political efforts failed to gain either public or congressional support. By the end of his term, his disapproval rating reached 77 percent, and Americans began to look toward the Republican Party again.

Camp David Accords

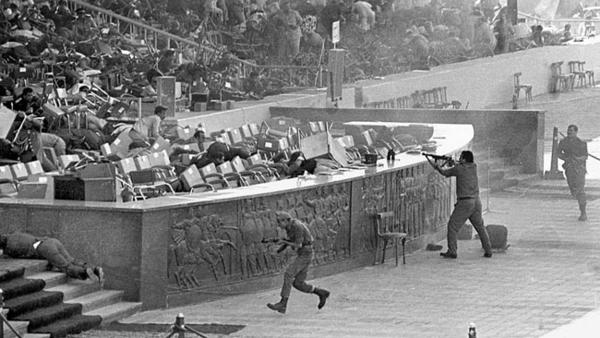

In perhaps his greatest presidential success, Carter brokered a peace agreement between Israel and Egypt through the Camp David Accords of 1978-79 with Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat, and Israeli, Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Acting as both mediator and participant, he persuaded the two leaders to end a 30-year state of war. In this, Egypt officially recognized the State of Israel—the first and only Muslim nation in the Middle East to do so. The subsequent peace treaty was signed at the White House in March 1979.

A Harbinger of things to come

Having made peace with Israel, Egypt was summarily expelled from the Arab League, and Sadat was assassinated in 1981 as a corrupt westernizer. As Egyptian officials hunted down Sadat’s killers, many would flee to the mountains of Afghanistan. There the Saudi-born Osama Bin laden was fighting to expel the Soviets who had rolled into Afghanistan to support a teetering new Communist revolutionary government in that mountain nation.

Video (00:12:10) : The Presidents Carter (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43181&loid=452178)

Ceding the Canal

In one of his more controversial measures, Carter signed the treaty promising to return the Panama Canal to Panama—an unpopular measure with most Americans because it would, in effect, turn over a strategic American asset to a dictatorial government. After protracted and often emotional debate, Carter also secured Senate ratification of treaties ceding the Panama Canal to Panama by the year 2000.

Going a step farther than Nixon, he extended formal diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China. But Carter enjoyed less success with the Soviet Union. Though he assumed office with détente at high tide and declared that the United States had escaped its “inordinate fear of Communism,” his insistence that “our commitment to human rights must be absolute” antagonized the Soviet government. A SALT II agreement further limiting nuclear stockpiles was signed, but not ratified by the U.S. Senate, many of whose members felt the treaty was unbalanced. The 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan killed the treaty and triggered a Carter defense build-up that paved the way for the huge expenditures of the 1980s.

Video (00:03:52) Cold War Battle for the Third World (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=8398&loid=412128)

1979: The Year of Impotence?

Under Nixon, the United States and Soviet Union had agreed to a Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty (SALT I). Under Carter, the United States and Soviet Union began discussions for SALT II in 1979. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan that year caused an official breakdown of the talks, though both sides honored the SALT II arrangements anyway. For his part, Carter ordered an American boycott of the Olympic Games scheduled for 1980 in the Soviet Union. Carter seemed to confirm public fears of a weak presidency when he followed what many considered a weak-kneed response to the Soviets with a speech in which he outlined his belief that Vietnam, Watergate, and the assassinations of the 1960s had created a “Crisis of Confidence” among the American people. Carter then asked Americans to conserve energy and called on his Cabinet to resign. In what clearly was shaping up to be a difficult year for Carter, the revolution in Iran could not have been welcome news.

Hostage Crisis in Iran

Carter’s most serious foreign policy challenge came in Iran. The American-backed Shah of Iran was overthrown by a mixture (though certainly not a coalition) of Democratic, Communist and Islamic Revolutionaries—each with their own vision for Iran’s future. After the Shah was admitted to the United States for cancer treatment, Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy and took 53 Americans hostage. The Shah had recognized Israel, given women the vote and, in the process, alienated the Shi’a clergy. His earlier program of reforms had not been democratic enough for liberal forces in Iran, too democratic for Communist forces and too western for Shi’a fundamentalists. While westernizing liberals had some early voice in the revolution, they were quickly drowned out by the supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini—a fundamentalist Shi’a Cleric. Khomeini and his supporters rapidly reinvented Iran as a state controlled by clerics, where females must wear the veil and burqa, were now marriageable at nine years of age instead of eighteen, and where public executions in the form of stoning and hanging were normative.The long-running hostage crisis dominated the final year of Carter’s presidency and greatly damaged his chances for re-election.

A SOCIETY IN TRANSITION

Shifts in the structure of American society, begun years or even decades earlier, had become apparent by the time the 1980s arrived. The composition of the population and the most important jobs and skills in American society had undergone major changes.

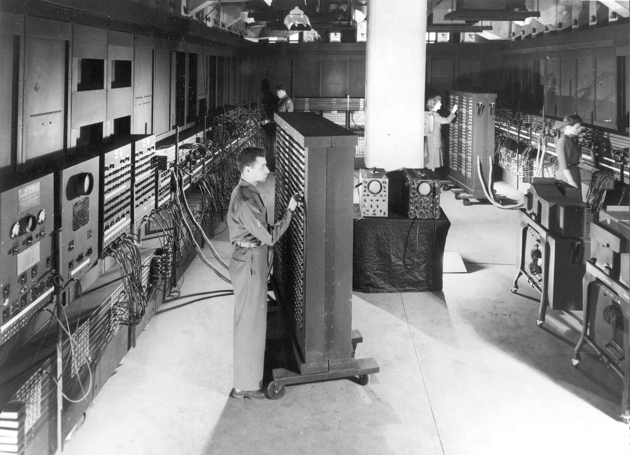

The dominance of service jobs in the economy became undeniable. By the mid-1980s, nearly three-fourths of all employees worked in the service sector, for instance, as retail clerks, office workers, teachers, physicians, and government employees.

Service-sector activity benefited from the availability and increased use of the computer. The information age arrived, with hardware and software that could aggregate previously unimagined amounts of data about economic and social trends. The federal government had made significant investments in computer technology in the 1950s and 1960s for its military and space programs.

In 1976, two young California entrepreneurs, working out of a garage, assembled the first widely marketed computer for home use, named it the Apple, and ignited a revolution. By the early 1980s, millions of microcomputers had found their way into U.S. businesses and homes, and in 1982, Time magazine dubbed the computer its “Machine of the Year.”

Meanwhile, America’s “smokestack industries” were in decline. The U.S. automobile industry reeled under competition from highly efficient Japanese carmakers. By 1980 Japanese companies already manufactured a fifth of the vehicles sold in the United States. American manufacturers struggled with some success to match the cost efficiencies and engineering standards of their Japanese rivals, but their former dominance of the domestic car market was gone forever. The giant old-line steel companies shrank to relative insignificance as foreign steelmakers adopted new technologies more readily.

Consumers were the beneficiaries of this ferocious competition in the manufacturing industries, but the painful struggle to cut costs meant the permanent loss of hundreds of thousands of blue-collar jobs. Those who could, made the switch to the service sector; others became unfortunate statistics.

Population patterns shifted as well. After the end of the postwar “baby boom” (1946 to 1964), the overall rate of population growth declined and the population grew older. Household composition also changed. In 1980 the percentage of family households dropped; a quarter of all groups were now classified as “nonfamily households,” in which two or more unrelated persons lived together.

New immigrants changed the character of American society in other ways. The 1965 reform in immigration policy shifted the focus away from Western Europe, facilitating a dramatic increase in new arrivals from Asia and Latin America. In 1980, 808,000 immigrants arrived, the highest number in 60 years, as the country once more became a haven for people from around the world.

Additional groups became active participants in the struggle for equal opportunity. Homosexuals, using the tactics and rhetoric of the Civil Rights movement, depicted themselves as an oppressed group seeking recognition of basic rights. In 1975, the U.S. Civil Service Commission lifted its ban on employment of homosexuals. Many states enacted anti-discrimination laws.

Then, in 1981, came the discovery of AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome). Transmitted sexually or through blood transfusions, it struck homosexual men and intravenous drug users with particular virulence, although the general population proved vulnerable as well. By 1992, over 220,000 Americans had died of AIDS. The AIDS epidemic has by no means been limited to the United States, and the effort to treat the disease now encompasses physicians and medical researchers throughout the world.

CONSERVATISM AND THE RISE OF RONALD REAGAN

The election year of 1980 saw former Democrat-turned Republican—Ronald Reagan receiving the Republican nomination. Carter followed up what appeared to many as a year of failure in 1979 with a failed attempt in 1980 to rescue the 52 American hostages in Iran. As the election season drew to a close, Carter’s chances at reelection dwindled. Negotiations to release the hostages, were completed a single day before Reagan’s inaugural and the hostages were released during the ceremony itself which added to the perception that Reagan was feared by America’s enemies and would be a tough, no-nonsense president.

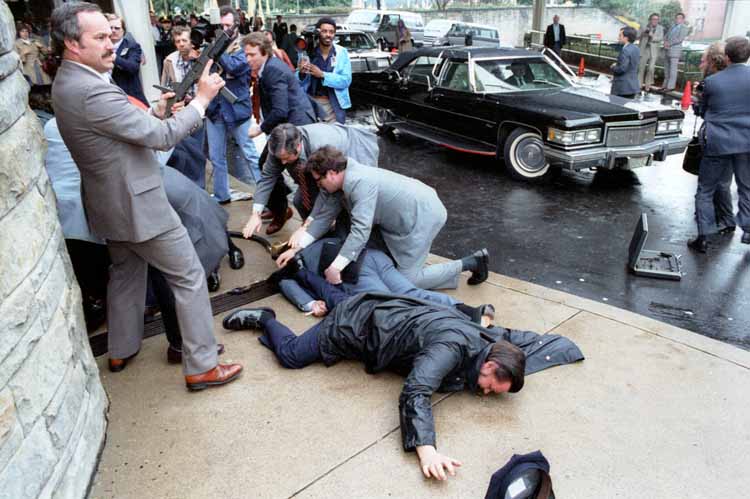

Ronald Reagan began his presidency by getting shot. Surviving this, he repudiated Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech by telling Americans that this “Vietnam Syndrome” must not hamper America’s determination to secure the peace and maintain its strategic resources—especially in the face of Soviet aggression in Czechoslovakia in the late 1960s followed by the Soviet misadventure into Afghanistan in 1979. An arms build-up which had begun late in the Carter Administration was put into high gear under Reagan. With Soviet influence in the Middle East apparently growing and U.S. influence simultaneously shrinking, the U.S. began funneling aid to Pakistan to support the Afghan Mujahadeen resistance to the Soviets.

For many Americans, the economic, social, and political trends of the previous two decades — crime and racial polarization in many urban centers, challenges to traditional values, the economic downturn and inflation of the Carter years — engendered a mood of disillusionment. It also strengthened a renewed suspicion of government and its ability to deal effectively with the country’s social and political problems.

Conservatives, long out of power at the national level, were well positioned politically in the context of this new mood. Many Americans were receptive to their message of limited government, strong national defense, and the protection of traditional values.

The Moral Majority

This conservative upsurge had many sources. A large group of fundamentalist Christians were particularly concerned about crime and sexual immorality. They hoped to return religion or the moral precepts often associated with it to a central place in American life. One of the most politically effective groups in the early 1980s, the Moral Majority, was led by a Baptist minister, Jerry Falwell. Another, led by the Reverend Pat Robertson, built an organization, the Christian Coalition, that by the 1990s was a significant force in the Republican Party. Using television to spread their messages, Falwell, Robertson, and others like them developed substantial followings.

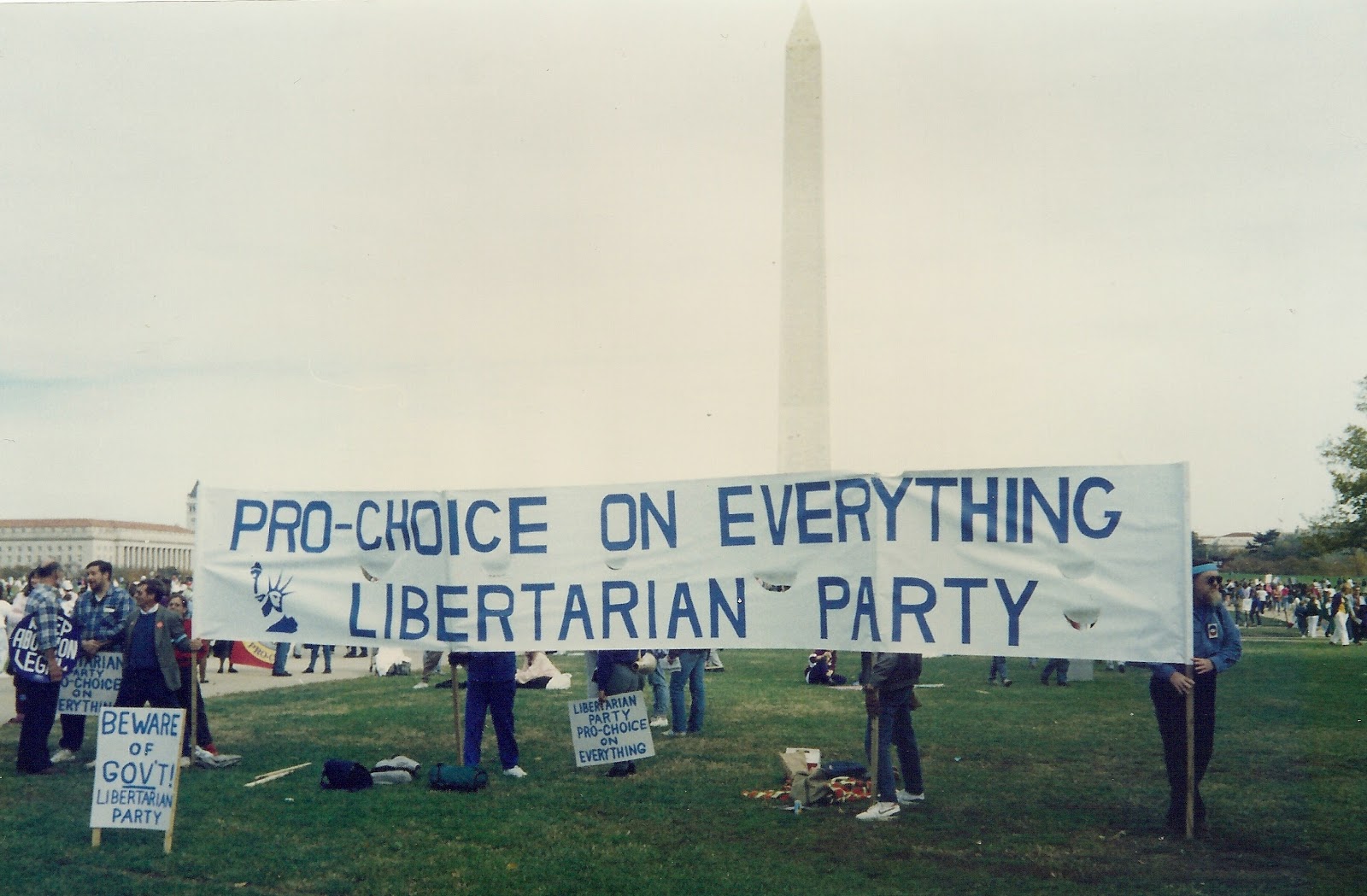

Another galvanizing issue for conservatives was divisive and emotional: abortion. Opposition to the 1973 Supreme Court decision, Roe v. Wade, which upheld a woman’s right to an abortion in the early months of pregnancy, brought together a wide array of organizations and individuals. They included, but were not limited to, Catholics, political conservatives, and religious evangelicals, most of whom regarded abortion under virtually any circumstances as murder. Pro-choice and pro-life (that is, pro- and anti-abortion rights) demonstrations became a fixture of the political landscape.

Within the Republican Party, the conservative wing grew dominant once again. They had briefly seized control of the Republican Party in 1964 with its presidential candidate, Barry Goldwater, then faded from the spotlight. By 1980, however, with the apparent failure of liberalism under Carter, a “New Right” was poised to return to dominance.

Using modern direct mail techniques as well as the power of mass communications to spread their message and raise funds, drawing on the ideas of conservatives like economist Milton Friedman, journalists William F. Buckley and George Will, and research institutions like the Heritage Foundation, the New Right played a significant role in defining the issues of the 1980s.

The “Old” Goldwater Right had favored strict limits on government intervention in the economy. This tendency was reinforced by a significant group of “New Right” “libertarian conservatives” who distrusted government in general and opposed state interference in personal behavior. But the New Right also encompassed a stronger, often evangelical faction determined to wield state power to encourage its views. The New Right favored tough measures against crime, a strong national defense, a constitutional amendment to permit prayer in public schools, and opposition to abortion.

The figure that drew all these disparate strands together was Ronald Reagan. Reagan, born in Illinois, achieved stardom as an actor in Hollywood movies and television before turning to politics. He first achieved political prominence with a nationwide televised speech in 1964 in support of Barry Goldwater. In 1966 Reagan won the governorship of California and served until 1975. He narrowly missed winning the Republican nomination for president in 1976 before succeeding in 1980 and going on to win the presidency from the incumbent, Jimmy Carter.

Video (00:02:49): Reagan (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43181&loid=94214)

President Reagan’s unflagging optimism and his ability to celebrate the achievements and aspirations of the American people persisted throughout his two terms in office. He was a figure of reassurance and stability for many Americans. Wholly at ease before the microphone and the television camera, Reagan was called the “Great Communicator.”

Taking a phrase from the 17th century Puritan John Winthrop, he told the nation that the United States was a “shining city on a hill,” invested with a God-given mission to defend the world against the spread of Communist totalitarianism.

Reagan believed that government intruded too deeply into American life. He wanted to cut programs he contended the country did not need, and to eliminate “waste, fraud, and abuse.” Reagan accelerated the program of deregulation begun by Jimmy Carter. He sought to abolish many regulations affecting the consumer, the workplace, and the environment. These, he argued, were inefficient, expensive, and detrimental to economic growth.

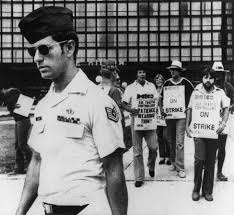

Reagan also reflected the belief held by many conservatives that the law should be strictly applied against violators. Shortly after becoming president, he faced a nationwide strike by U.S. air transportation controllers. Although the job action was forbidden by law, such strikes had been widely tolerated in the past. When the air controllers refused to return to work, he ordered them all fired. Over the next few years the system was rebuilt with new hires.

THE ECONOMY IN THE 1980s

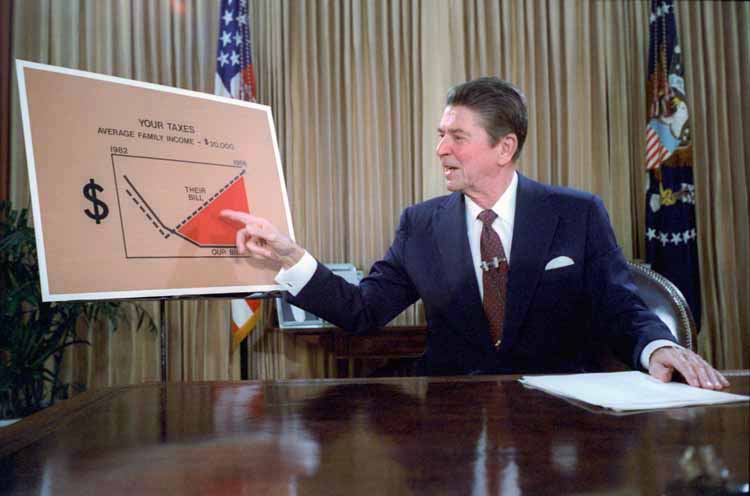

President Reagan’s domestic program was rooted in his belief that the nation would prosper if the power of the private economic sector was unleashed. The guiding theory behind it, “supply side” economics, held that a greater supply of goods and services, made possible by measures to increase business investment, was the swiftest road to economic growth. Accordingly, the Reagan administration argued that a large tax cut would increase capital investment and corporate earnings, so that even lower taxes on these larger earnings would increase government revenues.

Despite only a slim Republican majority in the Senate and a House of Representatives controlled by the Democrats, President Reagan succeeded during his first year in office in enacting the major components of his economic program, including a 25-percent tax cut for individuals to be phased in over three years. The administration also sought and won significant increases in defense spending to modernize the nation’s military and counter what it felt was a continual and growing threat from the Soviet Union.

Under Paul Volcker, the Federal Reserve’s draconian increases in interest rates squeezed the runaway inflation that had begun in the late 1970s. The recession hit bottom in 1982, with the prime interest rates approaching 20 percent and the economy falling sharply. That year, real gross domestic product (GDP) fell by 2 percent; the unemployment rate rose to nearly 10 percent, and almost one-third of America’s industrial plants lay idle. Throughout the Midwest, major firms like General Electric and International Harvester released workers. Stubbornly high petroleum prices contributed to the decline. Economic rivals like Germany and Japan won a greater share of world trade, and U.S. consumption of goods from other countries rose sharply.

Farmers also suffered hard times. During the 1970s, American farmers had helped India, China, the Soviet Union, and other countries suffering from crop shortages, and had borrowed heavily to buy land and increase production. But the rise in oil prices pushed up costs, and a worldwide economic slump in 1980 reduced the demand for agricultural products. Their numbers declined, as production increasingly became concentrated in large operations. Those small farmers who survived had major difficulties making ends meet.

The increased military budget — combined with the tax cuts and the growth in government health spending — resulted in the federal government spending far more than it received in revenues each year. Some analysts charged that the deficits were part of a deliberate administration strategy to prevent further increases in domestic spending sought by the Democrats. However, both Democrats and Republicans in Congress refused to cut such spending. From $74 billion in 1980, the deficit soared to $221billion in 1986 before falling back to $150 billion in 1987.

The deep recession of the early 1980s successfully curbed the runaway inflation that had started during the Carter years. Fuel prices, moreover, fell sharply, with at least part of the drop attributable to Reagan’s decision to abolish controls on the pricing and allocation of gasoline. Conditions began to improve in late 1983. By early 1984, the economy had rebounded. By the fall of 1984, the recovery was well along, allowing Reagan to run for re-election on the slogan, “It’s morning again in America.” He defeated his Democratic opponent, former Senator and Vice President Walter Mondale, by an overwhelming margin.

Video (00:04:25) Morning in America (http://www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/ronald-reagan/videos/morning-in-america)

The United States entered one of the longest periods of sustained economic growth since World War II. Consumer spending increased in response to the federal tax cut. The stock market climbed as it reflected the optimistic buying spree. Over a five-year period following the start of the recovery, gross national product grew at an annual rate of 4.2 percent. The annual inflation rate remained between 3 and 5 percent from 1983 to 1987, except in 1986 when it fell to just under 2 percent,the lowest level in decades. The nation’s GNP grew substantially during the 1980s; from 1982 to 1987, its economy created more than 13 million new jobs.

Steadfast in his commitment to lower taxes, Reagan signed the most sweeping federal tax-reform measure in 75 years during his second term. This measure, which had widespread Democratic as well as Republican support, lowered income tax rates, simplified tax brackets, and closed loopholes.

However, a significant percentage of this growth was based on deficit spending. Moreover, the national debt, far from being stabilized by strong economic growth, nearly tripled. Much of the growth occurred in skilled service and technical areas. Many poor and middle-class families did less well. The administration, although an advocate of free trade, pressured Japan to agree to a voluntary quota on its automobile exports to the United States.

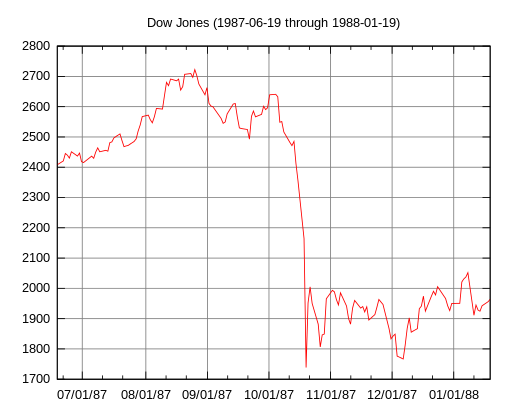

The economy was jolted on October 19, 1987, “Black Monday,” when the stock market suffered the greatest one-day crash in its history, 22.6 percent. The causes of the crash included the large U.S. international trade and federal-budget deficits, the high level of corporate and personal debt, and new computerized stock trading techniques that allowed instantaneous selling of stocks and futures. Despite the memories of 1929 it evoked, however, the crash was a transitory event with little impact. In fact, economic growth continued, with the unemployment rate dropping to a 14-year low of 5.2 percent in June 1988.

FOREIGN AFFAIRS

Video (00:08:06) : Reagan (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43181&loid=452180)

In foreign policy, Reagan sought a more assertive role for the nation, and Central America provided an early test. The United States provided El Salvador with a program of economic aid and military training when a guerrilla insurgency threatened to topple its government. It also actively encouraged the transition to an elected democratic government, but efforts to curb active right-wing death squads were only partly successful. U.S. support helped stabilize the government, but the level of violence there remained undiminished. A peace agreement was finally reached in early 1992.

Nicaragua

U.S. policy toward Nicaragua was more controversial. In 1979 revolutionaries calling themselves Sandinistas overthrew the repressive right-wing Somoza regime and established a pro-Cuba, pro-Soviet dictatorship. Regional peace efforts ended in failure, and the focus of administration efforts shifted to support for the anti-Sandinista resistance, known as the contras.

Following intense political debate over this policy, Congress ended all military aid to the contras in October 1984, then, under administration pressure, reversed itself in the fall of 1986, and approved $100 million in military aid. However, a lack of success on the battlefield, charges of human rights abuses, and the revelation that funds from secret arms sales to Iran (see below) had been diverted to the contras undercut congressional support to continue this aid.

Subsequently, the administration of President George H.W. Bush, who succeeded Reagan as president in 1989, abandoned any effort to secure military aid for the contras. The Bush administration also exerted pressure for free elections and supported an opposition political coalition, which won an astonishing upset election in February 1990, ousting the Sandinistas from power.

The Reagan administration was more fortunate in witnessing a return to democracy throughout the rest of Latin America, from Guatemala to Argentina. The emergence of democratically elected governments was not limited to Latin America; in Asia, the “people power” campaign of Corazon Aquino overthrew the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, and elections in South Korea ended decades of military rule.

By contrast, South Africa remained intransigent in the face of U.S. efforts to encourage an end to racial apartheid through the controversial policy of “constructive engagement,” quiet diplomacy coupled with public endorsement of reform. In 1986, frustrated at the lack of progress, the U.S. Congress overrode Reagan’s veto and imposed a set of economic sanctions on South Africa. In February 1990, South African President F.W. de Klerk announced Nelson Mandela’s release and began the slow dismantling of apartheid.

Despite its outspoken anti-Communist rhetoric, the Reagan administration’s direct use of military force was restrained. On October 25, 1983, U.S. forces landed on the Caribbean island of Grenada after an urgent appeal for help by neighboring countries. The action followed the assassination of Grenada’s leftist prime minister by members of his own Marxist-oriented party. After a brief period of fighting, U.S. troops captured hundreds of Cuban military and construction personnel and seized caches of Soviet-supplied arms. In December 1983, the last American combat troops left Grenada, which held democratic elections a year later.

The Middle East, however, presented a far more difficult situation. A military presence in Lebanon, where the United States was attempting to bolster a weak, but moderate pro-Western government, ended tragically, when 241 U.S. Marines were killed in a terrorist bombing in October 1983. In April 1986, U.S. Navy and Air Force planes struck targets in Tripoli and Benghazi, Libya, in retaliation for Libyan instigated terrorist attacks on U.S. military personnel in Europe.

In the Persian Gulf, the earlier breakdown in U.S.-Iranian relations and the Iran-Iraq War set the stage for U.S. naval activities in the region. Initially, the United States responded to a request from Kuwait for protection of its tanker fleet; but eventually the United States, along with naval vessels from Western Europe, kept vital shipping lanes open by escorting convoys of tankers and other neutral vessels traveling up and down the Gulf.

In late 1986 Americans learned that the administration had secretly sold arms to Iran in an attempt to resume diplomatic relations with the hostile Islamic government and win freedom for American hostages held in Lebanon by radical organizations that Iran controlled. Investigation also revealed that funds from the arms sales had been diverted to the Nicaraguan contras during a period when Congress had prohibited such military aid.

The ensuing Iran-contra hearings before a joint House-Senate committee examined issues of possible illegality as well as the broader question of defining American foreign policy interests in the Middle East and Central America. In a larger sense, the hearings were a constitutional debate about government secrecy and presidential versus congressional authority in the conduct of foreign relations. Unlike the infamous Senate Watergate hearings 14 years earlier, they found no grounds for impeaching the president and could reach no definitive conclusion about these perennial issues.

U.S.-SOVIET RELATIONS

In relations with the Soviet Union, President Reagan’s declared policy was one of peace through strength. He was determined to stand firm against the country he would in 1983 call an “evil empire.” Two early events increased U.S.-Soviet tensions: the suppression of the Solidarity labor movement in Poland in December 1981, and the destruction with 269 fatalities of an off-course civilian airliner, Korean Airlines Flight 007, by a Soviet jet fighter on September 1, 1983. The United States also condemned the continuing Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and continued the aid begun by the Carter administration to the mujahedeen resistance there.

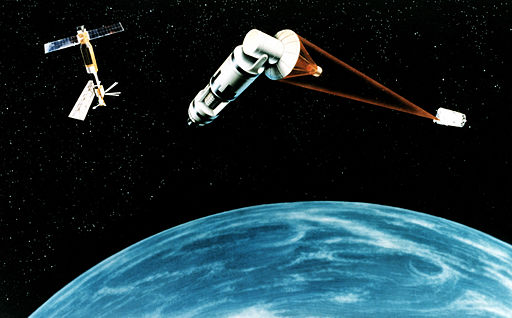

During Reagan’s first term, the United States spent unprecedented sums for a massive defense buildup, including the placement of intermediate- range nuclear missiles in Europe to counter Soviet deployments of similar missiles. And on March 23, 1983, in one of the most hotly debated policy decisions of his presidency, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) research program to explore advanced technologies, such as lasers and high-energy projectiles, to defend against intercontinental ballistic missiles. Although many scientists questioned the technological feasibility of SDI and economists pointed to the extraordinary sums of money involved, the administration pressed ahead with the project.

After re-election in 1984, Reagan softened his position on arms control. Moscow was amenable to agreement, in part because its economy already expended a far greater proportion of national output on its military than did the United States. Further increases, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev felt, would cripple his plans to liberalize the Soviet economy.

In November 1985, Reagan and Gorbachev agreed in principle to seek 50-percent reductions in strategic offensive nuclear arms as well as an interim agreement on intermediate- range nuclear forces. In December 1987, they signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty providing for the destruction of that entire category of nuclear weapons. By then, the Soviet Union seemed a less menacing adversary. Reagan could take much of the credit for a greatly diminished Cold War, but as his administration ended, almost no one realized just how shaky the USSR had become.

Reagan’s early Cold War rhetoric of an “Evil Empire” had been greatly tempered by the genuine friendship that developed between the Soviet Premier –Mikhail Gorbachev-- and himself. Realizing that the Soviet system was failing, Gorbachev had embarked on two programs to save Soviet Communism. “Glasnost” or “openness” provided freedom of information and transparency in the Soviet system and “Perestroika” sought to reform the soviet economic system. Trying to match the U.S. missile for missile for 40 years had all but bankrupted a soviet economy which was already dysfunctional. The new openness and economic reforms would quickly permeate the Soviet satellite states. A wave of rebellion in 1989 would topple the Romanian and East German governments, Bring the Berlin Wall down and, in 1991, bring an end to the Soviet Union itself.

THE PRESIDENCY OF GEORGE H. W. BUSH

President Reagan enjoyed unusually high popularity at the end of his second term in office, but under the terms of the U.S. Constitution he could not run again in 1988. The Republican nomination went to Vice President George Herbert Walker Bush, who was elected the 41st president of the United States.

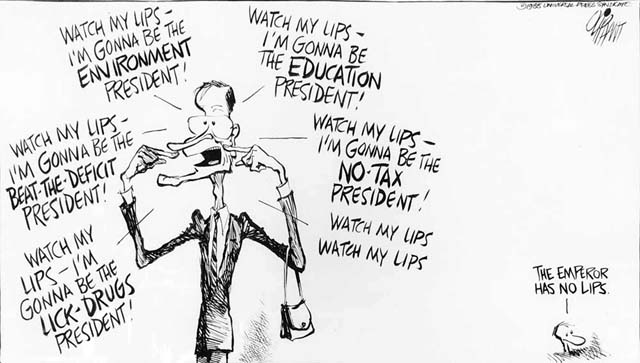

Bush campaigned by promising voters a continuation of the prosperity Reagan had brought. In addition, he argued that he would support a strong defense for the United States more reliably than the Democratic candidate, Michael Dukakis. He also promised to work for “a kinder, gentler America.” Dukakis, the governor of Massachusetts, claimed that less fortunate Americans were hurting economically and that the government had to help them while simultaneously bringing the federal debt and defense spending under control. The public was much more engaged, however, by Bush’s economic message: No new taxes. In the balloting, Bush finished with a 54-to-46-percent popular vote margin.

During his first year in office, Bush followed a conservative fiscal program, pursuing policies on taxes, spending, and debt that were faithful to the Reagan administration’s economic program. But the new president soon found himself squeezed between a large budget deficit and a deficit-reduction law. Spending cuts seemed necessary, and Bush possessed little leeway to introduce new budget items.

The Bush administration advanced new policy initiatives in areas not requiring major new federal expenditures. Thus, in November 1990, Bush signed sweeping legislation imposing new federal standards on urban smog, automobile exhaust, toxic air pollution, and acid rain, but with industrial polluters bearing most of the costs. He accepted legislation requiring physical access for the disabled, but with no federal assumption of the expense of modifying buildings to accommodate wheelchairs and the like. The president also launched a campaign to encourage volunteerism, which he called, in a memorable phrase, “a thousand points of light.”

BUDGETS AND DEFICITS

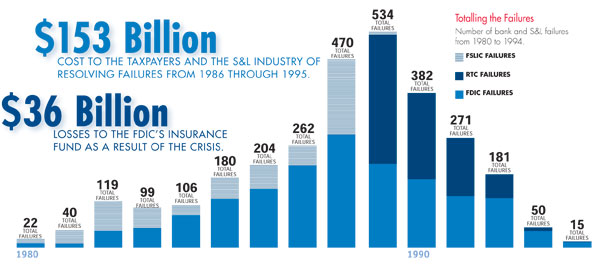

Bush administration efforts to gain control over the federal budget deficit, however, were more problematic. One source of the difficulty was the savings and loan crisis. Savings banks — formerly tightly regulated, low-interest safe havens for ordinary people — had been deregulated, allowing these institutions to compete more aggressively by paying higher interest rates and by making riskier loans. Increases in the government’s deposit insurance guaranteed reduced consumer incentive to shun less-sound institutions. Fraud, mismanagement, and the choppy economy produced widespread insolvencies among these thrifts (the umbrella term for consumer-oriented institutions like savings and loan associations and savings banks). By 1993, the total cost of selling and shuttering failed thrifts was staggering, nearly $525billion.

In January 1990, President Bush presented his budget proposal to Congress. Democrats argued that administration budget projections were far too optimistic, and that meeting the deficit-reduction law would require tax increases and sharper cuts in defense spending. That June, after protracted negotiations, the president agreed to a tax increase. All the same, the combination of economic recession, losses from the savings and loan industry rescue operation, and escalating health care costs for Medicare and Medicaid offset all the deficit-reduction measures and produced a shortfall in 1991 at least as large as the previous year’s.

Video (00:06:56) : George H.W. Bush (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43181&loid=452180)

END TO THE COLD WAR

When Bush became president, the Soviet empire was on the verge of collapse. Gorbachev’s efforts to open up the USSR’s economy appeared to be floundering. In 1989, the Communist governments in one Eastern European country after another simply collapsed, after it became clear that Russian troops would not be sent to prop them up. In mid-1991, hard-liners attempted a coup d’etat, only to be foiled by Gorbachev rival Boris Yeltsin, president of the Russian republic. At the end of that year, Yeltsin, now dominant, forced the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Video (00:19:54): End of an Empire (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=8398&loid=412123)

The Bush administration adeptly brokered the end of the Cold War, working closely with Gorbachev and Yeltsin. It led the negotiations that brought the unification of East and West Germany (September 1990), agreement on large arms reductions in Europe (November 1990), and large cuts in nuclear arsenals (July 1991). After the liquidation of the Soviet Union, the United States and the new Russian Federation agreed to phase out all multiple-warhead missiles over a 10-year period. The disposal of nuclear materials and the ever-present concerns of nuclear proliferation now superseded the threat of nuclear conflict between Washington and Moscow.

End of the Cold War (Alternative Version)

While the Soviet economy deteriorated and Afghan fighters exacted a heavier toll using Afghan blood and American arms supplied by the C.I.A., Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms of glasnost and perestroika were gaining traction in the Soviet homeland. The economic reforms of perestroika could not save the Soviet economy and the openness of glasnost meant more public input on (mostly against) the war in Afghanistan. In 1989, the Soviet Union left Afghanistan and quickly imploded upon itself. The Cold War had ended. Osama Bin Laden credited Islam and the Afghan resistance with, not only the local win against the Soviets, but the collapse of the Soviet Union itself.

New World Order

While Carter and Reagan’s military expenditures certainly helped bankrupt the Soviet Union, the collapse itself occurred during the presidency of George Bush Senior. President Bush found himself at the helm during what he termed “A New World Order.” The Cold War which had defined domestic and international politics for half a century left a power vacuum in the world and nobody was quite sure what would, or should, fill it.

THE GULF WAR

The euphoria caused by the drawing down of the Cold War was dramatically overshadowed by the August 2, 1990, invasion of the small nation of Kuwait by Iraq. Saddam Hussein justified his invasion of the tiny and extremely wealthy nation by claiming that Kuwait was both a province of Iraq and that it was stealing Iraqi oil.Iraq, under Saddam Hussein, and Iran, under its Islamic fundamentalist regime, had emerged as the two major military powers in the oil-rich Persian Gulf area. The two countries had fought a long, inconclusive war in the 1980s. Less hostile to the United States than Iran, Iraq had won some support from the Reagan and Bush administrations. The occupation of Kuwait, posing a threat to Saudi Arabia, changed the diplomatic calculation overnight.

Building a Coalition

President Bush strongly condemned the Iraqi action, called for Iraq’s unconditional withdrawal, and sent a major deployment of U.S. troops to the Middle East. He assembled one of the most extraordinary military and political coalitions of modern times, with military forces from Asia, Europe, and Africa, as well as the Middle East.

In the days and weeks following the invasion, the U.N. Security Council passed 12 resolutions condemning the Iraqi invasion and imposing wide-ranging economic sanctions on Iraq. On November 29, it approved the use of force if Iraq did not withdraw from Kuwait by January 15, 1991. Gorbachev’s quickly imploding Soviet Union, once Iraq’s major arms supplier, made no effort to protect its former client.

Bush also confronted a major constitutional issue. The U.S. Constitution gives the legislative branch the power to declare war. Yet in the second half of the 20th century, the United States had become involved in Korea and Vietnam without an official declaration of war and with only murky legislative authorization. On January 12, 1991, three days before the U.N. deadline, Congress granted President Bush the authority he sought in the most explicit and sweeping war-making power given a president in nearly half a century.

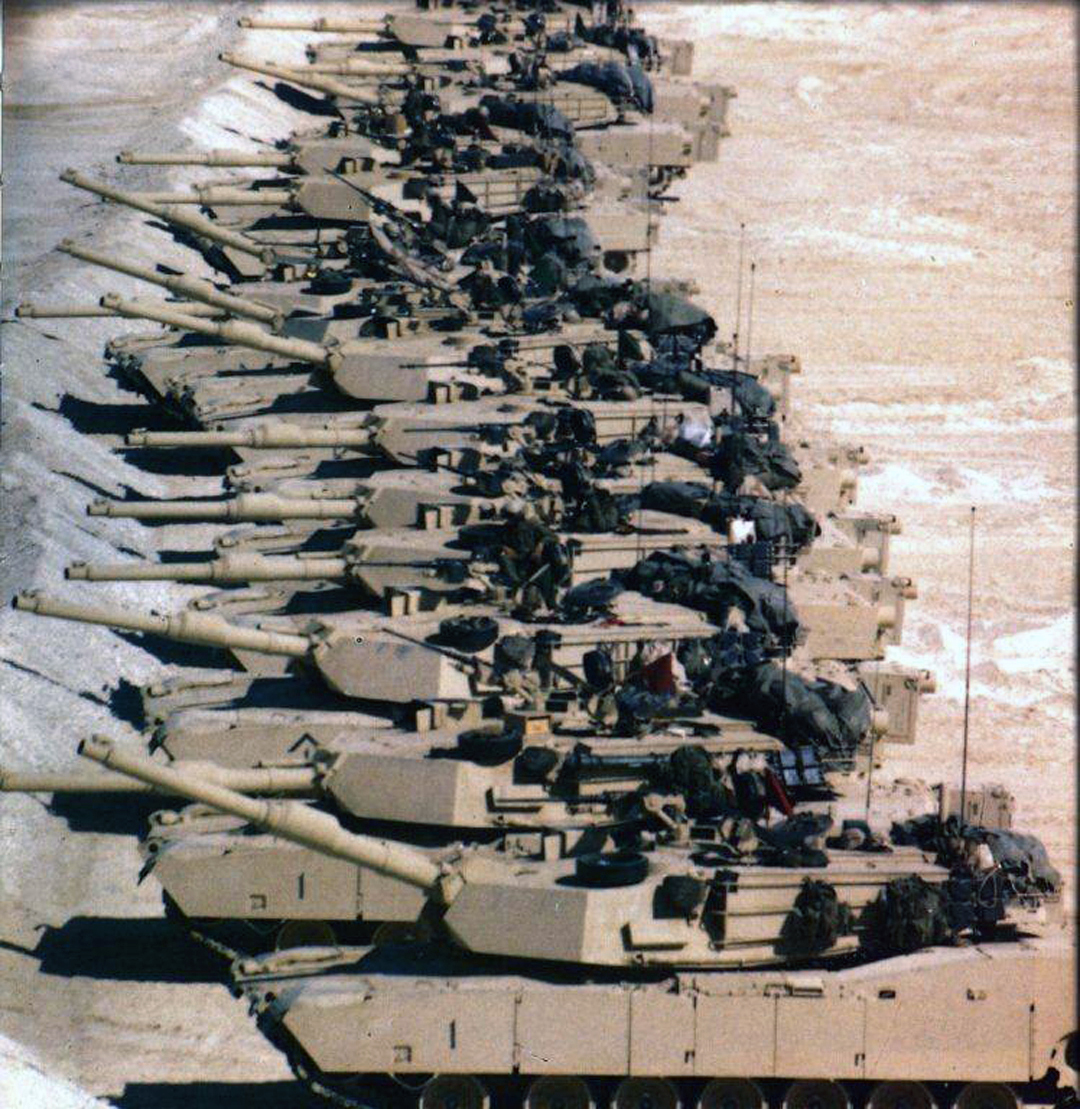

Desert Storm

The United States, in coalition with Great Britain, France, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other countries, succeeded in liberating Kuwait with a devastating, U.S.-led air campaign that lasted slightly more than a month. It was followed by a massive invasion of Kuwait and Iraq by armored and airborne infantry forces. With their superior speed, mobility, and firepower, the allied forces overwhelmed the Iraqi forces in a land campaign lasting only 100 hours.

In an effort to redefine the war into an Arab-Israeli conflict –thereby gaining Arab support—Hussein had authorized scud missile attacks on Israel. American success at keeping Israel from entering the conflict ensured that the Arab states would not support Iraq. “No-Fly” zones were established over portions of Iraq to keep Hussein from rebuilding his military strength and to protect Iraqi Kurds in the North.

Aftermath

The victory, however, was incomplete and unsatisfying. The U.N. resolution, which Bush enforced to the letter, called only for the expulsion of Iraq from Kuwait. Saddam Hussein remained in power, savagely repressing the Kurds in the north and the Shiites in the south, both of whom the United States had encouraged to rebel. Hundreds of oil-well fires, deliberately set in Kuwait by the Iraqis, took until November 1991 to extinguish. Saddam Hussein’s regime also apparently thwarted U.N. inspectors who, operating in accordance with Security Council resolutions, worked to locate and destroy Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear facilities more advanced than had previously been suspected and huge stocks of chemical weapons.

The Gulf War enabled the United States to persuade the Arab states, Israel, and a Palestinian delegation to begin direct negotiations aimed at resolving the complex and interlocked issues that could eventually lead to a lasting peace in the region. The talks began in Madrid, Spain, on October 30, 1991. In turn, they set the stage for the secret negotiations in Norway that led to what at the time seemed a historic agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, signed at the White House on September 13, 1993.

PANAMA AND NAFTA

The president also received broad bipartisan congressional backing for the brief U.S. invasion of Panama on December 20, 1989, that deposed dictator General Manuel Antonio Noriega. In the 1980s, addiction to crack cocaine reached epidemic proportions, and President Bush put the “War on Drugs” at the center of his domestic agenda. Moreover, Noriega, an especially brutal dictator, had attempted to maintain himself in power with rather crude displays of anti-Americanism. After seeking refuge in the Vatican embassy, Noriega turned himself over to U.S. authorities. He was later tried and convicted in U.S. federal court in Miami, Florida, of drug trafficking and racketeering.

On the economic front, the Bush administration negotiated the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Mexico and Canada. It would be ratified after an intense debate in the first year of the Clinton administration.

THIRD-PARTY AND INDEPENDENT CANDIDATES

The United States is often thought of as functioning under a two-party system. In practical effect this is true: Either a Democrat or a Republican has occupied the White House every year since 1852. At the same time, however, the country has produced a plethora of third and minor parties over the years. For example, 58 parties were represented on at least one state ballot during the 1992 presidential elections. Among these were obscure parties such as the Apathy, the Looking Back, the New Mexico Prohibition, the Tish Independent Citizens, and the Vermont Taxpayers.

Third parties organize around a single issue or set of issues. They tend to fare best when they have a charismatic leader. With the presidency out of reach, most seek a platform to publicize their political and social concerns.

The most successful third-party candidate of the 20th century was a Republican, Theodore Roosevelt , the former president. His Progressive or Bull Moose Party won 27.4 percent of the vote in the 1912 election. The progressive wing of the Republican Party, having grown disenchanted with President William Howard Taft, whom Roosevelt had hand-picked as his successor, urged Roosevelt to seek the party nomination in 1912. This he did, defeating Taft in a number of primaries. Taft controlled the party machinery, however, and secured the nomination.

Roosevelt’s supporters then broke away and formed the Progressive Party. Declaring himself as fit as a bull moose (hence the party’s popular name), Roosevelt campaigned on a platform of regulating “big business,” supporting women’s suffrage, and a graduated income tax, as well as the Panama Canal, and conservation. His effort was sufficient to defeat Taft. By splitting the Republican vote, however, he helped ensure the election of the Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Socialists. The Socialist Party also reached its high point in 1912, attaining 6 percent of the popular vote. Perennial candidate Eugene Debs won nearly 900,000 votes that year, advocating collective ownership of the transportation and communication industries, shorter working hours, and public works projects to spur employment. Convicted of sedition during World War I, Debs campaigned from his cell in 1920.

Robert La Follette. Another Progressive was Senator Robert La Follette, who won more than 16 percent of the vote in the 1924 election. Long a champion of farmers and industrial workers, and an ardent foe of big business, La Follette was a prime mover in the recreation of the Progressive movement following World War I. Backed by the farm and labor vote, as well as by Socialists and remnants of Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party, La Follette ran on a platform of nationalizing railroads and the country’s natural resources. He also strongly supported increased taxation on the wealthy and the right of collective bargaining. He carried only his home state of Wisconsin.

Henry Wallace. The Progressive Party reinvented itself in 1948 with the nomination of Henry Wallace, a former secretary of agriculture and vice president under Franklin Roosevelt. Wallace’s 1948 platform opposed the Cold War, the Marshall Plan, and big business. He also campaigned to end discrimination against African Americans and women, backed a minimum wage, and called for the elimination of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. His failure to repudiate the U.S. Communist Party, which had endorsed him, undermined his popularity and he wound up with just over 2.4 percent of the popular vote.

Dixiecrats. Like the Progressives, the States Rights or Dixiecrat Party, led by South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond, emerged in 1948 as a spin-off from the Democratic Party. Its opposition stemmed from Truman’s civil rights platform. Although defined in terms of “states’ rights,” the party’s goal was continuing racial segregation and the “Jim Crow” laws that sustained it.

George Wallace. The racial and social upheavals of the 1960s helped bring George Wallace, another segregationist Southern governor, to national attention. Wallace built a following through his colorful attacks against civil rights, liberals, and the federal government. Founding the American Independent Party in 1968, he ran his campaign from the statehouse in Montgomery, Alabama, winning 13.5 percent of the overall presidential vote.

H. Ross Perot . Every third party seeks to capitalize on popular dissatisfaction with the major parties and the federal government. At few times in recent history, however, has this sentiment been as strong as it was during the 1992 election. A hugely wealthy Texas businessman, Perot possessed a knack for getting his message of economic common sense and fiscal responsibility across to a wide spectrum of the people. Lampooning the nation’s leaders and reducing his economic message to easily understood formulas, Perot found little difficulty gaining media attention. His campaign organization, United We Stand, was staffed primarily by volunteers and backed by his personal fortune. Far from resenting his wealth, many admired Perot’s business success and the freedom it brought him from soliciting campaign funds from special interests. Perot withdrew from the race in July. Re-entering it a month before the election, he won over 19 million votes as the Reform Party standard-bearer, nearly 19 percent of the total cast. This was by far the largest number ever tallied by a third-party candidate and second only to Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 showing as a percentage of the total.