- Author:

- Patricia Lauziere, Jennifer A Burns, PsyD, MA, RCPF

- Subject:

- Psychology, Social Work

- Material Type:

- Full Course

- Level:

- Community College / Lower Division

- Tags:

- License:

- Creative Commons Attribution

- Language:

- English

- Media Formats:

- Downloadable docs, eBook, Graphics/Photos, Text/HTML, Video

Addressing Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in SUD

Body Language Shape Personality

Brene Brown Empathy

Bridging Cultural Differences Playlist

Carl Rodgers Group Therapy

Child Abuse and Neglect

Creating Emotional Safety in Support Groups

Cultural Detective

Developing Group Facilitation Skills

Ethical Decision Making Worksheet

Getting Help

Good Relationships are Key to Healing Trauma

Ground Rules for Effective Groups

Group Activities

Group Dynamics

Group Facilitation

Group Facilitation 201 SAMSHA Presentation

Group Formation Task

Group Norms Activity

History of Psychotherapy

How Group Dynamics Effect Decisions

Intercultural Competence and Knowledge VALE Rubric

Lifetime affects of Trauma

Make Body Language your Super Power

Mental Health Treatment

Mindful Breathing

NIH Suicide Prevention

Paradox of TIC

SAFE-T

SAMHSA Trauma Informed Approach

Self-care Assessment

Status Quo in Decision Making

Strengths-based Interventions

Stress, Lifestyle, Health

Trauma Informed Care

Treatment Modalities

Unconscious Bias

Understanding Bias

What Every Counseling Psychologist Should Know

What is a Strengths-based Approach

What it takes to be racially literate

Work Group Basic Considerations

Dynamics of Interpersonal Relations I

Overview

Dynamics of Interpersonal Relations I, is an exploration of the small-group process through participation, interpretation and study. Major focus is on the class itself as an interacting group providing for personal, interpersonal, and intellectual challenge. The modules are designed for undergraduate students to become familiar with group dynamics. This resource has OpenStax text chapters, TedTalks and group activities.

Thank you to Jennifer Burns for sharing this resource.

Course Description

Exploration of the small-group process through participation, interpretation and study. Major focus is on the class itself as an interacting group providing for personal, interpersonal, and intellectual challenge.

Establishing Group Norms

Overview:

This section will cover establishing group norms, working agreements for the class (group). The various behaviors that are expected, should be outlined by the students. In doing so, this creates "buy-in" and It is important that students (group members) contribute their thoughts and expectations during the group development process. The ground rules suggested below should only be regarded as starting points for each group to adopt or adapt and prioritize. Allow the students to create their ground rules and or working agreements for the semester.

Learning Objectives:

1. Define group norms

2. Outline working agreements

3. Assess group processes

Ground rules and or working agreements are important for the success of group work. The following suggestions include some of the issues and starting points from which group members can be encouraged:

- Foster a culture of honesty. Successful group work relies on truthfulness. It is as dishonest for group members to 'put up with' something they don't agree about, or can't live with, as it is to speak untruthfully. However, remember it is important to temper honesty with tact.

- Remember you don't have to like the people in your group to work with them. In group work, as in professional life, people work with the team they are in, and matters of personal conflict need to be managed so they don't get in the way of the progress of the group as a whole.

- Affirm collective responsibility. Once issues have been aired, and group decisions have been made as fully as possible, they convention of collective responsibility needs to be applied for successful group processes. This leads towards everyone living with group decisions and refraining from articulating their own personal reservations outside the group.

- Develop and practice good listening skills. Every voice deserves to be heard, even if people don't initially agree with the point of view being expressed.

- Successful groups need full participation by group members. Group work relies on multiple perspectives. Do not hold back from putting forward your view. Work to value the opinion of others as well as your own.

- Everyone needs to take a fair share of the group work. This does not mean that everyone has to do the same thing. It is best when the members of the group have agreed how the tasks will be allocated among themselves. Be prepared to contribute by building on the ideas of others and validating the experiences of others.

- Working to strengths of individual members can benefit your group. The work of a group can be achieved efficiently when tasks are allocated according to the experience and expertise of each member of the group.

- However, groups offer a chance to develop strengths outside your comfort zone. Activities in groups can be developmental in purpose, so task allocation may be an ideal opportunity to allow you to build on areas of weakness or inexperience.

- Keep good records. There needs to be an output to look back upon. This can take the form of planning notes, minutes or other kinds of evidence of the progress of the work of the group. Rotate the responsibility for summing up the position of the group regarding the tasks in hand and recording this.

- Group deadlines are sacrosanct. The principle, 'You can let yourself down, but it's not OK to let the group down' underpins successful group work.

- Cultivate philanthropy. Group work sometimes requires you to make personal needs and wishes subordinate to the goal of the group. This is all the more valuable when other group members recognize that this is happening.

- Help people to value creativity and off-the-wall ideas. Don't allow these to be quelled out of a desire to keep the group on task, and strike a fair balance between progress and creativity.

- Enable systematic working patterns. Establishing a regular program of meetings, task report backs and task allocation is likely to lead to effective and productive group performance.

- Group ground rules can be modified. It can be productive to review and renegotiate the ground rules from time to time, creating new ones as solutions to unanticipated problems that might have arisen. It is important, however, not to forget or abandon those ground rules that proved useful in practice, but which were not consciously applied.

- Consequences for violating group ground rules are important. A group needs to recognize when it is not functioning and be able to take corrective action. Therefore, it is important that consequences for violating group ground rules be established from the start and that all group members agree and sign off on them.

"This work" is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Group Dynamics

Types of Groups:

Task Groups: Are formed for members to complete a project, for example a planning committee, community advocacy group, a study group, etc. Click here to learn more about task groups.

Psychoeducational Groups: Cognitive affective and behavioral skills, structured around a specific specialization (addressing triggers, self-harming behaviors, etc.). Click here to learn more about psychoeducational groups.

Counseling Groups: Are formed to provide clinical theories, to assist the group members with their healing process. Group members engage in an interpersonal process that promotes problem-solving strategies, in order to obtain coping skills to live with and manage their trauma and or maladaptive behavior. For example, HIV/AIDS group, domestic violence and or sexual trauma, etc. Click for group activities.

Psychotherapy Groups: Psychological problems, mental health diagnosis, deviant behaviors (domestic violence offenders, sex offenders, etc.) Click here to understand more about psychotherapy.

Self-help Groups: Non-clinical (Grief support groups, 12-step groups, cancer survivor, etc.) More information on self-help groups.

Brief Groups: Limited time, process orientated (this class) Limited time groups.

Culture: Values, beliefs and behaviors shared by a group of people. World view influences beliefs. More on Group dynamics.

Stages in Group Development

Exhibit 1:

Throughout her extensive work with teams and groups Burns (2019) has proposed one model of group development that consists of four stages. These four stages are building trust, managing conflict, shared purpose, and collaboration. (See Exhibit 1).

- Building Trust: During this stage, when group members first come together, emphases is usually placed on making acquaintances, sharing information, testing one another, and so forth. This stage is referred to as building trust. Group members attempt to discover which interpersonal behaviors are acceptable or unacceptable in the group. In this process of sensing out the environment, a new member is heavily dependent upon others for providing cues to acceptable behavior.

- Managing Conflict: In the second stage of group development, a high degree of intergroup conflict (defense mechanisms) can usually be expected as group members attempt to understand their role in the group and establish how they will or will not influence the development of group norms and roles.

- Shared Purpose: Over time, the group begins to develop a sense of oneness. Here, group norms emerge to guide individual behavior. Group members come to accept fellow members and develop a unity of purpose that binds them. Issues are discussed more openly, and efforts are made to clarify group goals.

- Collaboration: Once group members agree on basic purposes, they set about developing separate roles for the various members. In this stage, role differentiation emerges to take advantage of task specialization in order to facilitate goal attainment. The group focuses its attention on the task (collaborating). As we consider this simple model, it should be emphasized that Burns (2019), does not claim that all groups proceed through this sequence of stages. Rather, this model provides a generalized conceptual scheme to help us understand the processes by which groups form and develop over time.

Adapted from "Work Group: Basic Conderations" by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Treatment Modalities

Overview:

In this section students are introduced to some of the major theories of counseling. Group therapy is an integrative approach and students will learn to that there are multiple pathways and approaches to be an effective facilitator of group work.

Learning Outcomes:

1. Identify group therapy models

2. Understand the multicultural variables that arise in group work

3. Assess techniques that are grounded in theoretical framework

Psychodynamic Approach: is grounded in the understanding that our unconscious motivates our behavior and influences our personality. Sigmund Freud believed that our unconscious was a repository for socially unacceptable desires and our unconscious repressed traumatic and painful events. Group therapy that utilizes the psychodynamic concepts, focuses on "how the past, can influence the present" and the primary goal is to make the unconscious conscious.

Experimental Approach: is a person-centered approach that provides and understanding of the lens that the client experiences their world.

Cognitive Behavioral Approach: focuses on the role that one's thinking has on their behavior. CBT is an evidence-based practice that is a short term and a goal orientated approach.

As group counselors’, it is important to be flexible and adapt your modalities to meet the needs of the group. Being familiar with the diverse modalities will provide your clients with a healing group experience. Click here for more information on treatment modalities.

"This work" is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

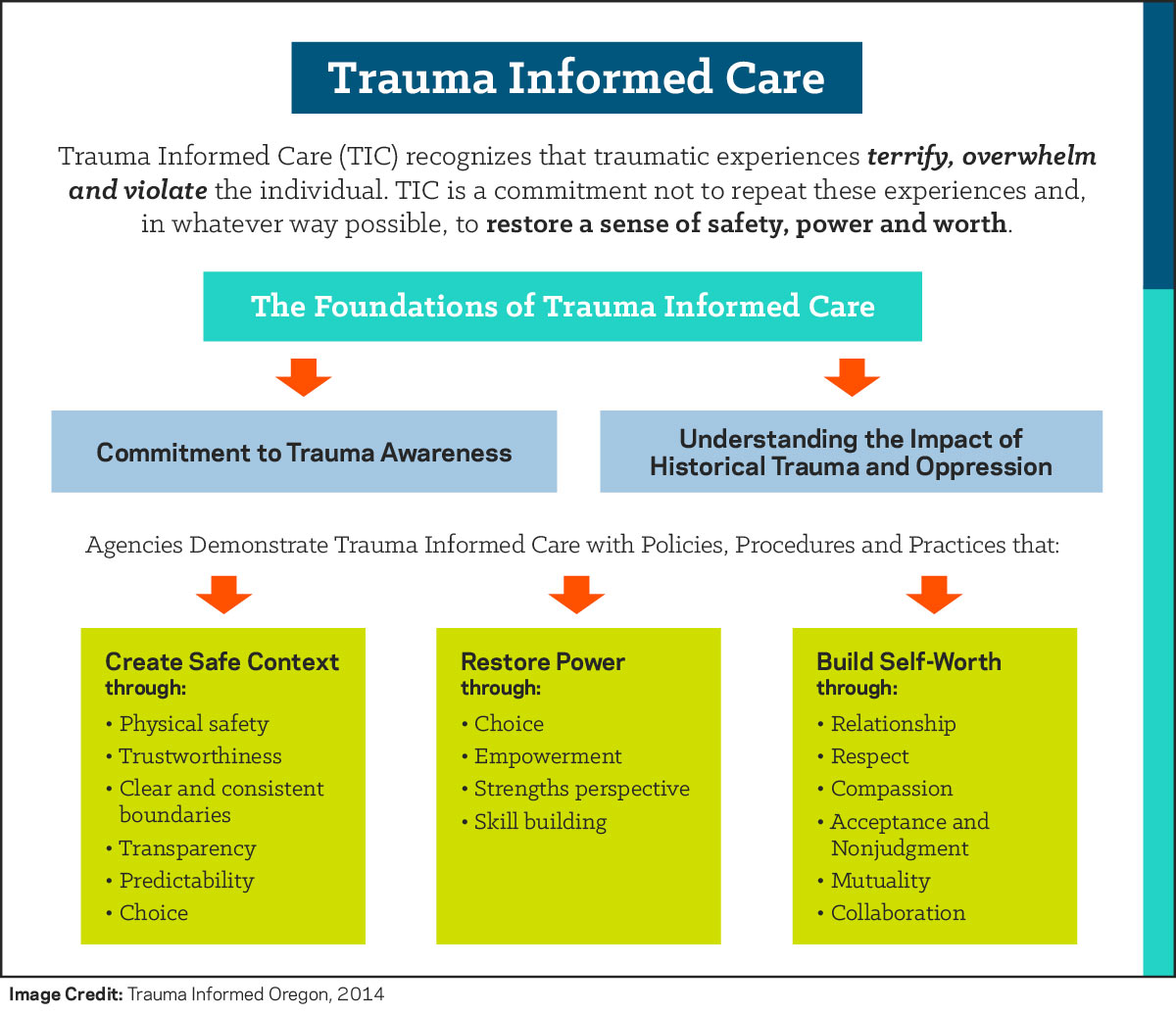

Trauma Informed Care

Trauma Informed Care, by design, helps treatment providers with the provision of services to individuals who have experienced trauma and trauma-related stressors. Considering that there is a high co-occurrence between substance use and trauma, it is recommended that substance abuse counselors understand the implications of Trauma Informed Care in order to provide the highest level of care to their patients.

The Prevalence of Trauma Experiences in Substance Use Populations

Trauma and symptoms of trauma are found frequently to be one of the co-occurring disorders with the highest prevalence rates for patients of substance use treatment.1, 2, 3 More specifically, it is estimated that individuals with a diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) engage in treatment for Substance Use Disorders (SUD) at a rate five times higher than the general population.1 In terms of practical considerations, this suggests that treatment teams providing SUD treatment are at greater likelihood of having patients with co-occurring trauma than many other mental health-related symptoms and diagnoses.

In treatment settings, there is a helpful distinction between: 1) treating the trauma experience and 2) treating the symptoms of trauma.1, 4, 5 This distinction is best understood as the difference between doing trauma processing therapy, which is implied when discussing treatment of the trauma experience, and helping to stabilize and treat the symptoms that occur as a response to the trauma experience. Although there are numerous evidence-based treatment approaches for treating the experience of trauma, not all providers (whether mental health or substance abuse counselors) have been both trained and deemed qualified to treat the trauma experience due to the specialized training and supervised experience the provision of such services would require.2, 6 As noted, this would have the potential to create a treatment gap between the number of trained providers in trauma care and the treatment needs of patients with trauma histories. Even though not every provider is trained to engage in trauma processing therapies, it is recommended that institutions train their professional staff in the ability to provide care that is sensitive to the unique symptoms of trauma.7 A structured approach that institutions can use for providing such care is known as Trauma Informed Care.2, 8

Trauma Informed Care Defined

Trauma Informed Care is a collection of approaches that translate the science of the neurological and cognitive understanding of how trauma is processed in the brain into informed clinical practice for providing services that address the symptoms of trauma.2, 8 These approaches are not designed for the treatment of the trauma experience (e.g., processing the trauma narrative), but rather for assistance in managing symptoms and reducing the likelihood of re-traumatization of the patient in the care experience.7, 9 As such, interventions of Trauma Informed Care are appropriate for a range of practitioners to utilize in a variety of clinical settings.

Trauma Informed Care is guided by the neurological understanding of how the threat-appraisal system of the brain, which includes the Hypothalamic-Pituitary Adrenal (HPA) axis, responds to trauma.10, 11 In addition to the HPA axis, Trauma Informed Care also pays close attention to the autonomic nervous system, which is the part of the central nervous system used to mediate arousal.10, 12 The autonomic nervous system is comprised of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. While the sympathetic nervous system increases activation (e.g., increased heart rate, higher respiration rate, etc.), the parasympathetic nervous system relaxes the system (e.g., lowered heart rate, decreased respiration rate, etc.).12

Many of the interventions implemented by the use of Trauma Informed Care act upon the autonomic nervous system to help reduce the otherwise often overstimulated sympathetic nervous system by increasing activation of the parasympathetic nervous system.2, 8, 10, 11

Three Main Ideas Highlighted with Trauma Informed Care

Although there are many important ideas presented as part of Trauma Informed Care, three common themes can be used to summarize many, but not all, of the main ideas. These three ideas, which are further expanded upon by SAMSHA,7 are: 1) Promote understanding of symptoms from a strengths-based approach, 2) minimize the risk of re-traumatizing the patient and 3) both offer and identify supports that are trauma informed. Additionally, SAMSHA7 underscores the importance of instilling hope for recovery as a thread running through all three of these approaches.

When working with patients, it is recommended to utilize a strengths-based approach that both empowers and provides hope to the patient that recovery from symptoms is possible.2, 9, 10 Often, this is recommended to start by providing psycho-education to the patient so they can understand how most symptoms associated with trauma and trauma responses are attempts made on a biological and cognitive level (including processes happening below the conscious level-of-awareness) to protect the individual from the risk of further harm.4, 10 For example, the increased activation and startle response experienced by individuals who have experienced trauma can be interpreted as an adaptation by the brain after trauma whereby the likelihood of being caught off guard is theoretically reduced, even at the cost of having a great number of 'false alarms.' 4, 5, 10, 11 Transforming the association that patients have with symptoms from being one of further hurt to potentially one of attempting protection can evoke a shift in how individuals relate to symptoms and can thereby increase a sense of hope for recovery.4, 10 If the individual can see how they are already trying to keep themselves safe, then it may be easier to help them transition to finding other, more effective means for coping.

Substance abuse counselors and mental health clinicians working with patients who have trauma histories are encouraged strongly to minimize the risk of re-traumatizing the patient.4, 9 As noted throughout the work by Friedman and colleagues, processing the trauma narrative before patients have sufficient coping skills and stabilization can cause further risk of harm and decompensation.4 As such, it is often not advised for clinicians to have patients feel forced to disclose trauma narratives (e.g., dispelling the myth that clinicians need to know all the details about a trauma before any work can be done), and it is additionally not often advised for patients to begin processing the trauma narrative while in short-term settings, as this is not necessarily treatment stability since the patient will need to transfer to another provider. Instead, patients are often best served by first establishing a sense of stability and safety.9 Once safety is established (as defined by stability, adequate supports and coping skills), then the patient is often in a better place to begin processing the trauma in appropriate settings that have the potential for long-term care, if needed.4, 9

Interventions aimed at connecting patients with supports and resources that are designed to be sensitive to the presence of symptoms of trauma is another major focus area in Trauma Informed Care.2 From an institutional point of view, this might include the regular use of a screener at intake to help identify the presence of symptoms associated with trauma, as well as providing referrals to providers who are best able to help patients at every stage of their treatment for symptoms of trauma.7, 9 This might also include providing patients with referrals to additional services beyond therapy, such as medication management, social support services or other supportive activities that the provider believes would be appropriate for the patient's specific symptoms and experiences.8

Implementing Trauma Informed Care with Seeking Safety

Practitioners in settings that provide substance use treatment that want to implement Trauma Informed Care principles may want to consider providing Seeking Safety groups.9 Developed by Najavits, Seeking Safety is an evidence-based practice approach to treating symptoms of trauma in a group setting.6, 9 Najavits designed Seeking Safety with the emphasis on fostering resilience and teaching coping skills for managing symptoms of trauma rather than processing trauma.9 In fact, Najavits understood that processing trauma with a patient before the patient has the skills to manage the symptoms of trauma successfully could be harmful. As such, the guidelines for implementing Seeking Safety groups includes establishing an understanding with participants that the purpose of the group is to learn skills and bolster resilience, not to process trauma narratives.

The Hazelden Betty Ford Experience

There is a strong correlation between trauma and addiction; research has shown that there is significant comorbidity of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorders prevalent in adults13 and adolescents,14 and studies have suggested that up to 95 percent of substance use disorder patients also report a history of trauma.15 As a result, Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation places a high value on the use of Trauma Informed Care for patient interventions. Our clinics use the Seeking Safety group model,9 as well as intensive, gender-specific, Trauma Informed Care groups based on Stephanie Covington's work with gender and trauma.16 The popularity of these groups among patients has encouraged Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation leaders to continue to develop and implement core programming that incorporates Trauma Informed Care into all of our clinical practices. Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation also emphasizes the use of Trauma Informed Care through education and training events, including staff in-service trainings and patient education sessions.

Questions & Controversies

Question: Instead of focusing on the symptoms of trauma, shouldn't patients just process the traumatic experience directly?

Response: In most instances, it is the preference of the provider to treat the source of a patient's concern, rather than treating the symptoms. However, there are few mental health providers who have completed the training and have required qualifications for processing traumatic events with patients, and the risks of attempting to process trauma too quickly or improperly can be lasting and severe. Since there is an imbalance in the number of clinicians with this training and the need for such services, and also since symptoms of trauma can be very pervasive and debilitating, Trauma Informed Care presents an alternative wherein a larger number of providers can work with patients to reduce trauma symptoms without needing to face the risks of incorrectly processing traumatic experiences.

How to Use This Information

Clinicians: Substance use counselors and mental health practitioners who are interested in learning more about the use of Trauma Informed Care are encouraged to explore further training opportunities on the topic, as well as exploring the resources made available that provide further detail on the topic, including an excellent Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) that does a wonderful job explaining this approach further.2

Patients: Trauma Informed Care is an opportunity to find healthy ways to reduce the severity of symptoms related to a trauma you may have experienced, but does not require you to process the details of your traumatic experience until you are ready. Talking to your counselor or therapist about exploring Trauma Informed Care can be a wonderful tool to reduce your symptoms in a safe, structured environment without having to commit to the direct processing of your traumatic event. You should never attempt to process a traumatizing event if you are not comfortable doing so, and any clinical professional who is working with you to process a traumatic experience should have specific training and experience in doing so; otherwise you could be put at risk of re-traumatization.

Conclusion

Due to the prevalence of co-occurring symptoms of trauma and substance use disorders, substance use counselors and mental health practitioners are encouraged to be familiar with the practices of Trauma Informed Care.7, 9 Trauma Informed Care promotes the use of strength-based approaches in a purposeful way to minimize the risk of re-traumatization of the patient.2, 5 By utilizing an understanding of trauma that is informed scientifically, Trauma Informed Care interventions are designed to be sensitive to the physiological, psychological and social modes through which the symptoms of trauma present.2, 8, 10

References

1. Atkins, C. (2014). Co-occurring disorders: Integrated assessment and treatment of substance use and mental disorders. Eau Claire, WI: PESI Publishing and Media.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 57. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4801. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration.

3. Development Service Group, Inc. (2015). Learning center literature review: Posttraumatic stress disorder. SAMHSA's National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices.

4. Friedman, M. J., Keane, T. M., & Resick, P. A. (2014). Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

5. Dass-Brailsford, P. (2007). A practical approach to trauma: Empowering interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

6. Dartmouth (2015). IDDT Integrated dual disorders treatment revised: Best practices, skills, and resources for successful client care. Center City, MN: Hazelden

7. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (2014). SAMHSA's concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

8. Curran, L. A. (2013). 101 trauma-informed interventions: Activities, exercises and assignments to move the client and therapy forward. Eau Claire, WI: PESI Publishing and Media.

9. Najavits, L. M. (2002). Seeking safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

10. van der Kolk, B. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

11. LeDoux, J. (2003). Synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

12. Anderson, J. R. (2014). Cognitive psychology and its implications (8th ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishing.

13. Tull, M. T., Berghoff, C. R., Wheeless, L., Cohen, R. T., & Gratz, K. L. (2017). PTSD symptom severity and emotion regulation strategy use during trauma cue exposure among patients with substance use disorders: Associations with negative affect, craving, and cortisol reactivity.

Behavior Therapy. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.05.005

14. Simmons, S., & Suárez, L. (2016). Substance abuse and trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25, 723-734.

15. Brown, P. J., Stout, R. L., & Mueller, T. (1999). Substance use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity: Addiction and psychiatric treatment rates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 13, 115-122.

16. Covington, S. S. (2007). Women and addiction: A gender responsive approach. Center City, MN: Hazelden.

Adapted from: The Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation

Non-Verbal Communication

Overview:

Do you know how to read people’s body language? When a group member rolls their eyes when you are talking, what are they “really” saying? What about a client that will not make eye contact, what does this say about the person? Being able to understand what participants are tying to convey with their body language is an important skill to have when facilitating a group. In this section we will explore non-verbal communication.

Learning Objectives:

1. Define non-verbal communication

2. Explain different types of non-verbal communication

It is safe to say that body language represents a very significant proportion of meaning that is conveyed and interpreted between people. Many body language experts and sources seem to agree that that between 50-80% of all human communications are non-verbal. So, while body language statistics vary according to situation, it is generally accepted that non-verbal communications are very important in how we understand each other (or fail to), especially in face-to-face and one-to-one communications, and most definitely when the communications involve an emotional or attitudinal element.

Body language is especially crucial when we meet someone for the first time.

We form our opinions of someone we meet for the first time in just a few seconds, and this initial instinctual assessment is based far more on what we see and feel about the other person than on the words they speak. On many occasions we form a strong view about a new person before they speak a single word. Body language is influential in forming impressions on first meeting someone.

The effect happens both ways - to and from:

When we meet someone for the first time, their body language, on conscious and unconscious levels, largely determines our initial impression of them. In turn when someone meets us for the first time, they form their initial impression of us largely from our body language and non-verbal signals.

And this two-way effect of body language continues throughout communications and relationships between people.

Body language is constantly being exchanged and interpreted between people, even though much of the time this is happening on an unconscious level.

Remember - while you are interpreting (consciously or unconsciously) the body language of other people, so other people are constantly interpreting yours.

The people with the most conscious awareness of, and capabilities to read, body language tend to have an advantage over those whose appreciation is limited largely to the unconscious.

You will shift your own awareness of body language from the unconscious into the conscious by learning about the subject, and then by practicing your reading of non-verbal communications in your dealings with others.

Adapted from: Very Well Mind

Exploring Bias

Overview: In this section, students will learn that unconscious bias is an automatic response that occurs without intention, or awareness. By exploring bias, students will become familiar with the hidden bias effect and develop a framework for self-reflective practice.

Learning Outcomes:

- Recognize when bias is present

- Examine bias and understand how it shows up in group dynamics

Bias is the impulse to judge without question.

Explore your biases here Project Implicit

"This work" is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Cultural Sensitivity

Overview:

In this section, it is important to provide a safe container for students to explore, understand and accept that cultural differences exist. Milton Bennett developed a framework that defines stages an individual may go through as they become culturally sensitive.

Learning Outcomes:

- Recognize cultural differences

- Practice an open-mind

- Demonstrate a willingness to understand culture

- Value cultural differences "This work" is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Ethical and Legal Considerations

Ethical Issues: Standards that govern conduct of professionals.

Legal Issues: Minimum standards society will tolerate, governed by local state and federal government. ex. Mandated reporters

American Counseling Association: Code of Ethics

Cultural Issues: A client’s ethnic background, race, gender, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, values and traditions. Ex. Food, gifts A Call to Profession

Informed Consent: Is a document that provides information about the group and process, every client has the right to freedom, automony and human dignity. Informed consent is a legal and ethical term defined in which a form is signed by the client, giving their permission to participate in group counseling.

Involuntary Membership: Clients are different and clients are usually mandated by an authoritive human service agency such as Department of Youth Services (DYS), Department of Childern and Famlies (DCF), Court, Probation, Parole, Registry of Motor Vechiles, ect.

Managing Psychological Risk: Click here

Confidentiality: APA Group guidelines

Questions to consider:

What measures do you take to ensure confidentiality?

Under what circumstances would you feel compelled to breach confidentiality?

A group member brings you a gift on a holiday?

What ethical issues may arise when working with a group of involuntary members?

In what ways would your personal values influence your work with group members?

"This work" is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Facilitator Competencies

Introduction to Facilitation

Facilitation is a technique used by trainers to help learners acquire, retain, and apply knowledge and skills. Participants are introduced to content and then ask questions while the trainer fosters the discussion, takes steps to enhance the experience for the learners, and gives suggestions. They do not, however, do the work for the group; instead, they guide learners toward a specific learning outcome.

Presentation vs. Facilitation

Presentation | Facilitation |

The presenter delivers information, usually through a lecture. | The facilitator enhances learning for everyone, usually through discussion or activities such as role plays. |

The presenter is the expert sharing their knowledge of the subject matter. | The facilitator provides opportunities for members of the group to share knowledge and learn from one another. |

The presenter spends most of the time talking. | The facilitator spends most of the time asking questions, encouraging others to speak, and answering learners’ questions during activities |

The presenter is usually on a stage or at the front of the room. | The facilitator is usually moving around the classroom to help address learners’ questions or monitor how activities are progressing |

Facilitator Skills

Facilitators can come from any background and a variety of experience levels. The best facilitators, however, demonstrate the following skills:

Listening. A facilitator needs to listen actively and hear what every learner or team member is saying.

Questioning. A facilitator should be skilled in asking questions that are open ended and stimulate discussion.

Problem solving. A facilitator should be skilled at applying group problem-solving techniques, including:

• defining the problem

• determining the cause

• considering a range of solutions

• weighing the advantages and disadvantages of solutions

• selecting the best solution

• implementing the solution

• evaluating the results.

Resolving conflict. A facilitator should recognize that conflict among group members is natural and, as long as it’s expressed politely, does not need to be suppressed. Conflict should be expected and dealt with constructively.

Using a participative style. A facilitator should encourage all learners or team members to actively engage and contribute in meetings, depending on their individual comfort levels. This includes creating a safe and comfortable atmosphere in which group members are willing to share their feelings and opinions.

Accepting others. A facilitator should maintain an open mind and not criticize ideas and suggestions offered by learners or group members.

Empathizing. A facilitator should be able to “walk a mile in another’s shoes” to understand the learners’ or team members’ feelings.

Leading. A facilitator must be able to keep the training or meeting focused toward achieving the outcome identified beforehand.

Self-care Practice

Overview: In this section, student will focus on creating a self-care plan.

Learning Outcomes:

- Understand the health benefits to a balanced life

- Practice self-reflection techniques to optimize health and wellness

Useful Links:

"This work" is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0