Primary Source Exemplar: Universal Declaration of Human Rights Social Science Unit

Note for Teachers

This lesson is best described as a primer for specific strategies that can be used to teach literacy. While somewhat thematically linked to the topic of human rights and how governments have guaranteed them, the primary source documents provided here should be introduced prior to beginning the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN UDHR) lesson sequence. They provide instruction for students in how to analyze dense primary source documents while demonstrating proven strategies and methodologies for teachers to use during the UN UDHR lesson sequence.

Before beginning to plan how you will teach reading strategies, you should make every attempt possible to see where your students are in terms of the skills and abilities they currently posses; no student can easily succeed when more is demanded of them then they can reasonably bear, nor will a student rise to their potential if unchallenged. If available, I strongly suggest acquainting yourself with prior standardized test scores (federal, state, local), as well as discussing the relative ability level of students with the prior instructors. You should also go out of your way to engage your students in appropriate, yet not school-centric discussions in order to gauge their general ability level, especially with English Language Learners, and their verbal fluency (which might not be accurately captured in the test results available).

These tasks, being foundational, work best when grading is based on completion and attentiveness to task, rather than on the end results. I have always felt that good teachers borrow and great teachers steal. To that end, I encourage you to steal these lessons and truly make them your own by customizing as you see fit.

Essential Questions

- How can one teach literacy skills while developing content knowledge?

- What are some of the more relevant strategies, and how can I employed them in my classroom?

Text Set

Magna Carta (1297 Revision) Translated 2007, US Archives

English Bill of Rights, Avalon Project (Yale)

US Declaration of Independence, US Archives

French Declaration of the Rights of Man, Avalon Project (Yale)

Student Resources

Annotating While Reading, Northcentral University Writing Center

'What I Really Want Is Someone Rolling Around In The Text', NYT, Article

Magna Carta (1297) Archaic Definitions

Online Fillable Tournament Bracket Creator

Key Concept Synthesis Worksheet

Costa's Three Levels of Inquiry - Handout (AVID)

Teacher Resources

Briefly Noted: Practicing Useful Annotation Strategies, NYT (for Teacher)

Elementary Reciprocal Teaching Lesson Plan w/video (adaptable)

Reciprocal Teaching - Adlit.org

Costa's Three Levels of Inquiry (For Teachers)

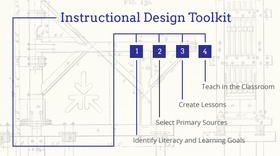

Tasks

1. Describe use and impact of annotating Primary Source Documents

2. Teach Specific Annotating and Marking up the Text Via MC

3. Utilize Reciprocal Teaching Methodology with EBoR

4. Explore Key Concept Synthesis with the US DoI

5. Demonstrate Costa’s 3 levels of inquiry with the FDoRM

Task 1: Describe use and impact of annotating Primary Source Documents

Preparation

Conduct reality check of all internet links for lesson

Print out article, 'What I Really Want Is Someone Rolling Around In The Text', enough copies for all students and two for yourself

Procure document camera, overhead projector, smart board, or similar to lead students in annotating the text

Examine Preconstructed lesson plan, ‘Briefly Noted: Practicing Useful Annotating Strategies’. Type up list of discussion questions from lesson

Conduct Freewrite of topic in Step 1 in case of odd numbers in your classroom (this allows you to observe students as they write)

Method

1. Ask students to think about how they treat books versus other documents. Which ones do they routinely write on? Which ones do they refrain from writing on? Have they ever practiced writing in the margin? Is it OK to write in a book at all? Does it matter what you write in the book? What happens with the internet, laptops, tablets, smartphones, ebooks, and digital publishing? Take some answers if students are so moved, but the purpose is simply to ‘prime the pump’

2. Define ‘Marginalia’ for students (the habit or form of writing in books, particularly useful annotations. Make explicit that routine vandalism is NOT Marginalia

3. Assign a 2 minute free write on the topic: ‘How important is marginalia? How can we keep the practice in the digital age?’ Ask students to aim for about ½ page written or ¼ page typed. Grade for completion and attentiveness to task only

4. Ask students to pair-share with someone near them. Be prepared to partner with a student if you have an odd number

5. The student with longer hair goes first. Give 39 seconds. Give the next student 22 seconds, but they only have to add thoughts they did not hear. NOTE: this could be taller, older, younger, shorter, lighter hair, darker

hair, alphabetical or anti-alphabetical order by first or last name,

etc. I use a spinning wheel to randomize it.

6. Ask for volunteers to raise their hand if their partner had an idea worth sharing. Write down a few names, then ask the people who raised their hand to explain the idea that their partner wrote about

7. Tell students that they are going to read an article about the lost art of marginalia, or writing in the margins. Give them 5 minutes. Circulate and monitor

8. After 4 minutes, assess their readiness to continue. If it seems they will need more tiem (likely), ask them, “Do you think you need another 4 minutes, or are you all just about finished?” Have them raise hands and vote. Give them the additional 4 minutes if the vote was even close

9. Invite students back and display the list of questions from the Briefly Noted lesson. Ask students to answer as a team and give 5 minutes, one minute per question. After 5 minutes, ask if they need an additional 2 minutes and allow them to vote (as above)

10. Call on random non-volunteers to report out their response to each question

11. Tell students that they are going to be working in pairs to finish annotating an article, but first the class will start together

12. Share with them the following simple annotation guide:

Number paragraphs (incl. single-sentence paragraphs) to quickly refer to paragraphs

Circle names (people, items or places), key terms and dates

Underline claims and evidence

Place arrows in the margin to respond to ideas

13. Make sure that the class numbers the paragraphs with you correctly

14. Model using the above by doing the first two paragraphs by yourself. There are opportunities for the remaining three types of annotations in those paragraphs

15. Stop and ask if there are any questions

16. For the next two paragraphs, give students 2 minutes to make annotations, then call on non-volunteers randomly to report their annotations. Correct and amplify their responses

17. Give students at least 30 minutes to finish marking up the document. Collect it at that point in time, or assign balance as homework. If assigned to complete as homework, check for completion the next class session and then allow students to share with their partners before collecting work. Grade for completion and attentiveness to task only

18. For enrichment, you can conduct the rest of the ‘Briefly Noted’ lesson, or assign a persuasive essay about the role of marginalia in the digital age using this article as a starting point

Standards

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text.

Rationale

Students are introduced to the concept of annotation through an explanation of marginalia and a discussion of how it can evolve in the digital age. Students also have guided practice including scaffolding for the process. Students are graded solely for completion and attentiveness to task only, which serves to reduce stress and allows the student to concentrate on learning the basics of annotating a text.

Task 2: Teach Specific Annotating and Marking up the Text Via MC

Preparation

Print copies of the Magna Carta (1297 revision) for the class, one per student with some extras

Prepare ‘March Madness’ style brackets for teams

Procure document camera, overhead projector, smart board, or similar to assist in filling out tournament bracket

Secure internet access for students to do their own research

Decide whether or not to ‘pre-teach’ problematic vocabulary. Only you know what your students are capable of and how best to interact with them. In my experience, preteaching vocabulary is ‘artificial’ and contrived; students generally retain vocabulary they have ‘picked up along the way’ better, as long as you take the time to ensure they actually understand it.*

Create appropriate tournament bracket with one slot for each student (e.g., if you have 25 students, 25 teams). If you have less than 37 students, consider assigning more than one article per student to your advanced or proficient students rather than cutting or combining articles

Determine if you wish to assign articles (advised) or let student choose randomly

* Likely problematic vocabulary includes: charter, freemen, perpetuity, relief (medieval sense), shilling, homage, whilst, aforesaid, recompense, disparagement, dower, distrained, chattels, common pleas (legal sense), novel disseisin, mort d’ancestor, justiciar, assizes of darrein presentment, lay fee, vill, respite, proxy, pence, demesne cart, kidelli (fish weir), praecipe, inquest, socage, burgage, exactions, escheat, barony, Michaelmas, advows, frankpledge, tithing, scuttle

Method

1. (Optional) pre-teach problematic vocabulary using the Frayer Model and assigning each student a word from the list. Have students report out their findings and share the Frayer Models. Collect, make bound copies, and distribute as a ‘glossary’ of difficult terms.

2. Explain to students that today they will be engaged in a highly competitive event, and that their votes matter. They will be judging an important matter

3. Review basic annotation technique from Task 1. Remind students of what they did to the article

4. Display Tournament Bracket on overhead. Tell them that they will be competing to determine which article of the Magna Carta is most important today

5. Assign articles to students, taking care to give larger assignments to students who are more advanced, and smaller articles to those who are struggling. If you feel as though students are all advanced or proficient you may wish to let them choose their own articles, but in this case you will want to ‘bunch together’ several of the smaller articles to make it equal to the work of one bigger article

6. Go over entire document numbering paragraphs. Because the articles are numbered, explain to students that you will call the first two paragraphs ‘A’ and ‘B’, and the last two ‘C’ and ‘D’ respectively. This will leave each of the articles with their own numbers as in the text. Explain that you modified the method because of the text, and that they need to remember to do that in the future

7. Tell students to annotate their articles referring to the glossary they made (if applicable). Explain that they are to. Give 5 minutes, then ask if the want another 2 minutes. If they vote affirmatively, provide them with the time

8. Ask them to write a basic summary capturing some of the most important elements of what they annotated. Make explicit that the annotations are to help them locate and identify key information in the passage. Give them 3 minutes

9. While students are completing the above, randomly assign students to the tournament bracket

10. Explain that each student will have 20 seconds to make the case that their article should move forward as the most important provision of the Magna Carta today. They can only use positive statements about their own article. They will be able to ask a question that the other person they are competing with will have to answer, as per the following schedule:

- Lower seed makes statement

- Higher seed makes statement

- Higher seed asks question

- Lower seed answers

- Lower seed asks question

- Higher seed answers

11. Ask students to raise their hands and vote who goes on. Each student can only vote once. Feel free to ignore students who are double voting, etc. The winner advances

12. Continue until the bracket is filled and you arrive at a winner. This might take a while, especially if you have students struggling to speak English. Consider making this a multiple day competition with only a handful of ‘bouts’ per day while you conduct other lessons

13. Collect all paragraph summaries

14. Check for understanding by asking students to write a brief paper debriefing the exercise. Students should answer the following aspects of the exercise: Was the winner based on the article, or ability of the speaker? Did the real most important article come out, or was there an important one that ‘lost’ along the way? What do they think the most important article was and why? What about the least important?

15. Post completed bracket, collate paragraph summaries, copy, and distribute

Standards

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze the cumulative impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone (e.g., how the language of a court opinion differs from that of a newspaper).

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.2 Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.3 Analyze how the author unfolds an analysis or series of ideas or events, including the order in which the points are made, how they are introduced and developed, and the connections that are drawn between them.

Task 3: Utilize Reciprocal Teaching Methodology with EBoR

NOTE: Reciprocal teaching is a strategy in which students are taught how to read by following four strategies, each one designed to get the student to think more critically about how they read and learn. The Four strategies are: Predicting, Questioning, Clarifying, and Summarizing. They are presented in order in this lesson, and conducted as whole-class exercises.

Ideally, Reciprocal teaching should be a small group activity (four students seems ideal), with students each taking turns in the four roles (predictor, questioner, clarifier, and summarizer), then rotating by paragraph (or other relevant milestone) with all students keeping a record of their learning. I have chosen to teach the relevant skill outside of the ideal practice to make it easier to explicitly teach the skills so that they may be later applied.

Preparation

Print out all sections of the English Bill of Rights, one per student

Prepare overhead projector/digital camera for whole class instruction

Review Reading Rockets Elementary Reciprocal Teaching Lesson with videoThis lesson can be easily adapted to use with any Primary Source Document where the primary concern is that the students will struggle with material above their comfort level, and is provided as an example of how reciprocal teaching is normally utilized

Method

- Invite students to brainstorm about what happens when they read. Allow 45 seconds. Call on 4-5 random non-volunteers, then switch to volunteers. Record comments for all to see

- If they don’t recognize that what happens may be different than what OUGHT to happen, prompt them with a cue: ‘Is this the way it should be? What could we do while reading to help figure out what is going on?”

- Record comments from volunteers

- Tell students that today you are going to show them a way to get started reading is a way that is good for studying

- Begin to read the English Bill of Rights. Do not hand out copies of the EBoR yet; project your copy with a blank paper ‘blocker’ and unview one line or section at a time. Pause at each line to translate into language the students will understand while asking students to make predictions about what might come next (See Note 1 below).

- When you get to the end of Note 1, have students pair off (preferably randomly) and make a series of predictions about the rest of the stuff that King John did. Have them record the predictions. Prepare to work with a student if there is an odd number. Select random non-volunteers to report out predictions

- Continue reading the litany of abuses, stopping at “All which are utterly and directly contrary to the known laws and statutes and freedom of this realm”

- Ask students to compare their predictions with the text. Give 1 minute, then ask pairs to come together to make groups of four (be prepared to step in if you don’t have the requisite number)

- Have groups of four to report out what they got right and what they got wrong. Explain that getting the prediction right or wrong is relatively unimportant; using your brain to make the prediction is what helps you remember the material and learn it more easily

- Ask each group of four to come up with 8 really good questions about the text so far. That should be two questions per person; give them about 2 minutes to complete this directive. Give another 2 minutes for each student to make sure they have copied down everyone else’s question. To assist struggling learners, consider making explicit that questions should be about things they did not understand, things that they thought were strange, or things which they know something else about (i.e. ‘Is this where our idea of specific rights came from?’)

- Have groups of four split back into 2 pairs with one caveat - they cannot be the same pairs that started. Each pair takes what they consider the best question and poses it to a pair they choose who has to comment on the question (they can answer it if they want, but that’s not the point). That group in turn gets to pick a question to ask any group that has not gone yet (and so on until all groups have asked questions - the last group asks the first group)

- Make explicit that asking meaningful questions is another way to help yourself learn and retain that learning. Depending on pacing, this might be a natural point to stop the class

- Hand out the physical copies of the EBoR

- Have students scan the portions you have already read and number them and the rest of the document

- Explain that they will be working with paragraph 17 (where you left off yesterday) and they will be in charge of translating it for you today! Pair them off

- Instruct each pair to read paragraph 17 and highlight areas they need to have clarified. If neither person has a highlighter, they can draw a box around the area (so that we don’t inadvertently confuse students about other annotations schema we have taught)

- Have pairs meet other pairs to work together in groups of 4 to clarify the areas. Ask students to look for areas where only one pair had marked for clarification first, and for groups to share. Groups then try to clarify remaining areas needing to be clarified. Give at least 8 minutes. Offer option of up to 3 more minutes if they vote for it. Circulate and try to guide students. If possible, allow students to use internet devices either you or they have available. If not, they will need to rely on dictionaries, encyclopedias, textbooks, and other paper sources and it might take longer

- Have each group of four join with another group and check their translation. Each ‘supergroup’ then picks which one translation they want to go with

- Call on groups in turn to report out their translation of paragraph 17, then ask students to return to their seats

- Explain that they have just taken the time to clarify parts of the selection that they found difficult at first. They did it by relying on friends, then breaking down the task and clarifying parts of the selection one at a time

- Continue to read to the group, translating paragraph 18

- When finished, tell students that you want them to work on summarizing the next 13 paragraphs, paragraph by paragraph. Give at least 12 minutes, with an option for 3 more. Circulate, assisting struggling learners

- Select random non-volunteers to report their summaries. Offer opportunities for those who had something different. Expand/amplify/redirect/question as appropriate after each comment is reported

- Explain that they have just taken the time to summarize part of the text to make it easier to understand and retain

- Explain that they have completed all four tasks in reciprocal teaching: predicting, questioning, clarifying, and summarizing.

- Close the lesson

- Option A - Finish with a quick summary of the last paragraphs

- Option B - Form groups of four and have students cover the remaining parts of the text using reciprocal teaching. See Reading Rockets Reciprocal Teaching Link

- Option C - Segue directly into a discussion of the importance of the Magna Carta and continuing lessons on the Democracy in Western Civilization strand of study.

NOTE 1:

All of the important leaders of the kingdom were there on that date in 1688, including William and Mary who were the Prince and Princess of Orange, and they made this official statement

Because the old King, John II, listened to bad advice from the people under him and tried to destroy the Protestant faith and mess up the laws and rights we had,…

{Stop and ask what might come next, have students write it down. Give 20 seconds then call on random non-volunteers}

By making new laws and forgetting old ones without checking with Parliament

By messing around with people who refused to go along with his illegal acts

{Stop and ask what might come next, have students write it down. Give 20 seconds then call on random non-volunteers}

By making a new court with new rights

By falsely taxing people more without checking with Parliament, specifically lying that Parliament had agreed to it

{Stop and ask what might come next, have students write it down. Give 20 seconds then call on random non-volunteers}

Standards

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary describing political, social, or economic aspects of history/social science.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.5 Analyze how a text uses structure to emphasize key points or advance an explanation or analysis.

Rationale

Students engage in a scaffolded reading of one of the more difficult foundational documents of Western Civilization designed to explicitly teach reciprocal teaching methodology, which can be adapted for use with any difficult passage.

Task 4: Explore Key Concept Synthesis with the US DoI

Preparation

Make copies of the US Declaration of Independence, enough for one for each student

Make copies of the Key Concept Synthesis Worksheet (found here), one per student

Method

Ask students if they have ever read a paragraph, then stopped to think about what they read, but couldn’t figure it out? How did that make them feel? Share that you sometimes get frustrated when reading the fine print on bills or when making large purchases, and that this is normal

Explain to students that they are going to learn a valuable skill both in their future history courses and in the real world. you are going to show them how to read quickly and effectively, while focusing on the key ideas and concepts they need to get from the reading. Make sure that you don’t ‘sell them a magic bullet’, but rather set expectations that you are showing them a process

Ask if they are ready to begin. You should model patience if they screw around for a few seconds, but gently remind them that you are waiting if they stray too long

Write two words (‘How’ and ‘today’) on the board, with a large enough space in between to write ‘doing’ later on (but hold off for now)

Quickly spout out a students name, point to the board wildly, and exclaim exictedly, “So? How about it? Huh? Gonna answer the question???” It helps to act a bit maniacal. Flip around to many different students, not giving any of them time to actually answer “How about YOU, Paul? Jesus? Sally, Antoine, ANYONE? Who can tell me how today, hmmmmm?”

Turn and look at the board, then act sheepish. “Ooops, I forgot something.” Write ‘doing’ in between ‘How’ and ‘today’

Jovially ask students to answer the question with a little bit of light banter

Ask students what made the question too difficult and frustrating to answer at first. Nudge students into recognizing that key words are the words that when you take them away make the sentence impossible to understand (or change you meaning drastically). Point out that what you wrote still isn’t a complete sentence (if you feel comfortable, explain what it needs to make it a complete sentence and fix it accordingly)

Explain that key concepts in reading selections work the same way - if you strip them out and toss them, you change the meaning or remove meaning altogether

Hand out the Declaration of Independence and invite student to investigate features of the text (but not read it). Point out the Title, the offset areas, the bolding, larger size font and the indenting. Ask them what they think is the most important clue? Have them write down the feature and their rationale on the back of the document. Ask random non-volunteers to report out their answers

Number the passages, making sure to number each paragraph even if it is a single sentence, and skipping the title ‘In Congress, July 4 1776 (i.e. ‘We hold these truths...’ is the third paragraph)

Read the first paragraph and second paragraphs aloud while students read it quietly

Ask students to annotate the first paragraph using the method shown in Task 1. Remind them if necessary

Ask students to write a brief 1 sentence summary, keeping only the key ideas. Be explicit that the toughest choices will be what to cut out to keep it to one sentence. Sample: When we are going to make a big change, it is only right that we explain exactly why.

Ask students to read the 3rd paragraph an annotate it as well. This time let them read silently. Give 5 minutes, with an option for 2 more. Circulate and monitor progress

Ask students to summarize the paragraph briefly in writing. Give two minutes, then ask students to ‘share and repair’ (share their summary with a partner who then gives feedback used to add detail, then the process is reversed)

Ask students to annotate paragraphs 4-30 (the offset section). Make explicit that they should rewrite in their own words in the margins. Give 8 minutes, with an option for another 3. (Optional) Instead of step 17, have the students practice reciprocal teacher as per task three

Ask students to pull out the top three general things that the King did that were bad. Explicitly state that they have to try to cover all of the crimes alleged in those three categories. Give 4 minutes, then have groups report out their categories, which you will record

Have students read and annotate paragraphs 31-33 and summarize. Give 5 minutes with an option for 2 more

Explain to students that they have been dealing with the key concepts of the US Declaration of Independence by breaking the document into pieces and figuring out the main idea of each piece. There is still more work to be done, however

Distribute the Key Concepts Synthesis handout. This worksheet is generic and is can be used for many other assignments. Keep in mind that this task is designed to teach (and model) instructional strategies to teach comprehension of difficult texts in the Social Sciences, and therefore the instructions on the worksheet will not be followed in this particular lesson

Instruct students that they need to go from what they have to distilling the 5 MOST IMPORTANT AND RELEVANT Key Concepts. Once again, the difficulty will lie in deciding what to leave out

(Optional) Give worksheet as homework and collect the next day. Select superior examples and make a small packet with names redacted to hand out to class. Students whose worksheets are selected should be given a moderate amount of extra credit

Standards

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.9-10.1a Introduce precise claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that establishes clear relationships among the claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.9-10.1c Use words, phrases, and clauses to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claim(s) and reasons, between reasons and evidence, and between claim(s) and counterclaims.

Rationale

Students practice pulling the key ideas out of texts by reference to skills they (hopefully) learned in earlier grades, and receive explicit instruction in using those skills if they did not learn them. In this case, the link between annotation, summarization, and identification of key concepts is made more clear

Task 5: Demonstrate Costa’s 3 levels of inquiry with the FDoRM

NOTE: Costa’s Three Levels of Inquiry are comparable and translatable to Blooms Taxonomy; I prefer Costa’s Three Levels as I find it generally easier to teach to my students, and for them to use as an ongoing reading strategy.

Preparation

Familiarize yourself with Costa’s Three Levels of Inquiry

Print physical copies of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man

Print Costa’s Three Levels of Inquiry Handout

Method

Ask students to think about the kinds of questions they get asked when teachers are checking to see if they did their assigned reading. Have students commit their thoughts to paper with a quick 30 second freewrite

Have 3-5 random non-volunteers to report out, then ask volunteers to fill in anything left out

Ask students to think if there are any other sorts of questions teachers usually ask, or another way to ask the same question, ‘if teachers sometimes ask questions for purposes other than to see if students did their reading. You may need to prompt that teachers sometime ask questions to find out if students understand, to find out what students know before hand, or to help in assigning grades (test questions)

Hand out the Costa’s Three Levels of Inquiry packet

Share with students the following explanation, “Each level is more complicated and builds on the one before. Level three questions are at the top - they take the most thought. Level two are in the middle, and they take some level of thought, but not too much. Level one questions are the basic level. They take very little thought, you just look something up. Level one question might be, What is my name? You don’t need to think really hard to figure out who I am (at least I hope not!). A level two question might be compare me as a teacher this year, with your teacher in the same subject last year (or two). You have to think about us both, and think about how we are alike and how we are different. A level three question might be predict which level of question I am going to want you to focus on for the rest of the year, and why?”

Guide students around the ‘house’ explaining the ways in which the various words can be used to make sentences of the appropriate level. Be explicit that this isn’t like some sort of magic formula. Point out that ‘Evaluate the expression x=2+1’ is not a level three question, but really more along the lines of level 1

Share, “As you can see, all of the questions are related and build on each other. If the level one question is ‘In 1492, who sailed the ocean blue?’, the answer would be Christopher Columbus. A level two question might be explain how the ‘discovery’ of North America by Columbus changed indigenous and European society. This requires you to know a lot of level one facts like the example question. A level three three question might be to judge: are the indigenous people of North America overall better off today having lived through the effects of the Columbian Exchange than if the crew had mutinied on Columbus and went back home? This requires you to explain things from a few different points of view - answer a few different level 2 questions. Each level builds on the ones that went before.”

Ask students to write a sample level one question on any school-appropriate topic. Give 30 seconds, then ask them to share with a partner. The partner should validate that it is a level one

Ask students to write a sample level two question on any school-appropriate topic. Give 40 seconds, then ask them to share with a partner. The partner should validate that it is a level two

Ask students to write a sample level three question on any school-appropriate topic. Give 60 seconds, then ask them to share with a partner. The partner should validate that it is a level three

Share with students that in the future, unless you specifically state otherwise the topic must be whatever you are discussing at the time, and the questions must be linked to each other as in the Columbus example above

Hand out the physical copy of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man

Instruct students to read the document, then annotate it

(Optional) Break students into smaller groups and practice Reciprocal Teaching

(Optional) Have students fill out the Key Concept Synthesis Form

Ask students to write 10 level one questions based on the text. Give 4 minutes with an optional extra minute

Tell students that you want them to write 5 level two questions, but there is a catch: each one has to be at least somewhat related to one of the 10 level one questions they wrote in step 16. Give them 3 minutes with an optional extra minute

Tell students that they have to write 2 GOOD level three questions, and each one has to be related to one of the level two questions from step 17

Have students pair up and share their questions. Each student should check to ensure that all of the questions are correctly identified and meet the requirements. Each partner must sign the page of the other, and is responsible for helping ensure that all questions are correctly labeled

Explain that they have been learning how to create questions at different levels, and using differing amounts of thinking. Let them know that while level 3 questions might seem the most important, in truth all of the levels are like a system that reinforces the others. Assure them that with practice level 3 questions will begin to come naturally

Close the lesson

(Option A) Have students write an additional level three question as homework. Tomorrow have them work the process in reverse (they have to write 3 level two questions related to the level three, and then 6 level one questions related to the level two questions). This will help solidify the internal structure of the three levels of inquiry and how they interact. Collect and grade for completion and attentiveness; call both the student and their pair-partner and correct deficiencies two-on-one at your desk while the class completes a reading assignment (but don’t dock points)

(Option B) Collect and grade for completion and attentiveness; call both the student and their pair-partner and correct deficiencies two-on-one at your desk while the class completes a reading assignment (but don’t dock points). Explain to students that you want them to write a summary of what you did today as homework. The next day ask them to freewrite about what they thought of the strategy, if they think was easy or difficult, if it gave them insight into how teachers ask questions. Explain that they just completed the basics of a homework assignment called SR3Q.

This is the only normal homework I assign: students write a summary, a reflection, and one of each level of question each night. The topic has to be what we’ve done in class that day. I ask them to submit their best of the preceding week on Friday.

(Option C) Assign an essay with a twist: the prompt is one of their level three questions, and they have to write a complete essay answering the question fully, and also answering all (or some if you have them write a lot) of the level two and level one questions they wrote

Standards

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text.

Rationale

Students are exposed to Costa’s Three Levels of Inquiry and taught how to write questions at all three levels, while also grappling with the primary source document directly.